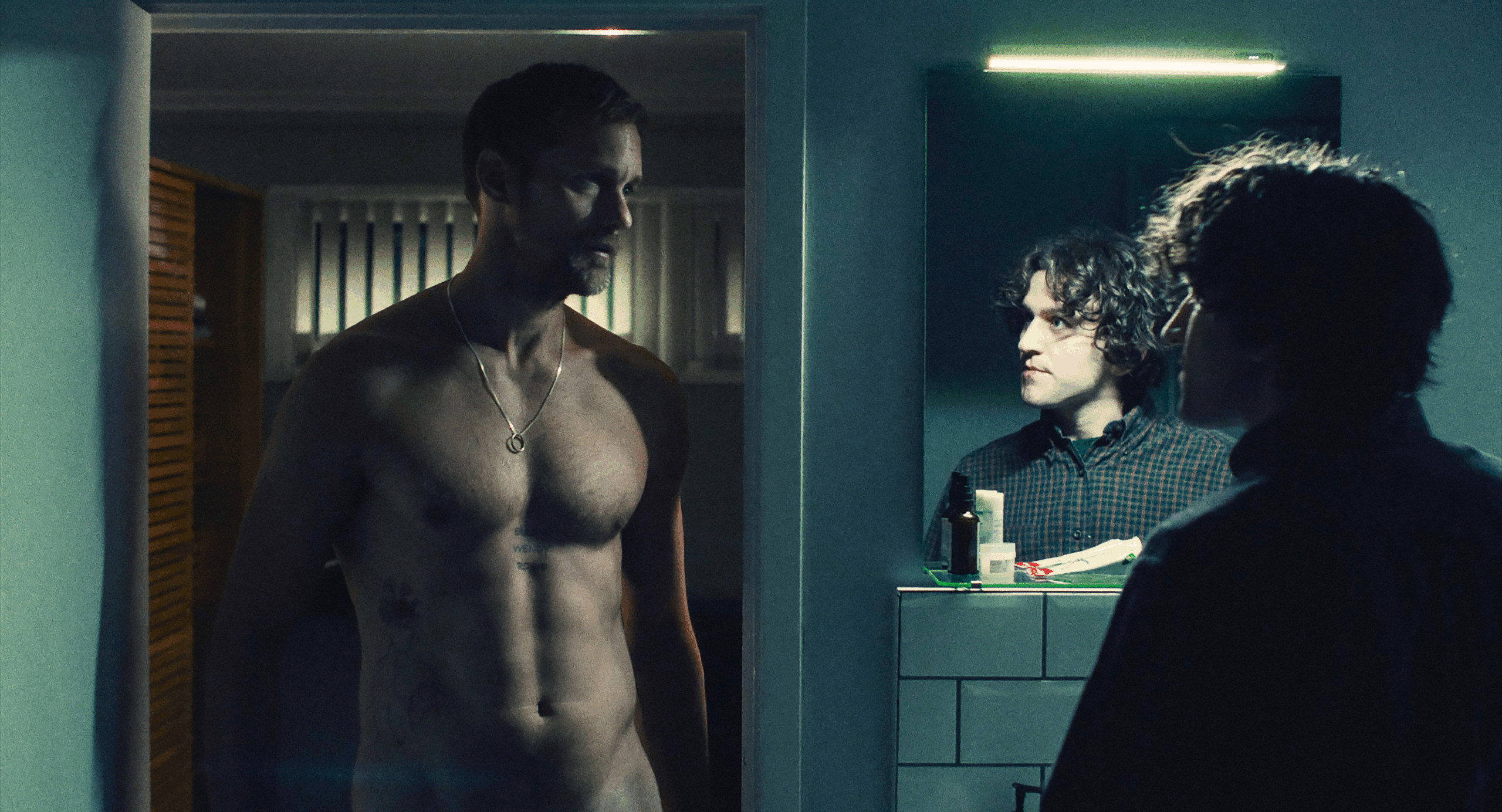

If you were anywhere on the Internet last year, you probably saw Alexander Skarsgård before you heard of Pillion. He turned heads on the red carpet with a series of BDSM-lite sartorial choices: thigh-high Saint Laurent boots at Cannes; a sleeveless Ludovic de Saint Sernin halter and tie paired with corseted leather trousers at the BFI London Film Festival; a silky cream blouse printed with a still life of creams, serums, and dildos at the Zurich Film Festival. This was the press tour for Harry Lighton’s debut feature, which quickly turned Skarsgård into the film’s most visible marketing asset.But he’s only half of the equation. Pillion, which refers to the passenger seat on a motorcycle (otherwise known as the bitch seat), also belongs to Harry Melling, who plays Colin, the film’s forlorn and doe-eyed protagonist. His timidity and optimism can be neatly summarized by his choice of work and leisure: He spends his days handing out parking tickets and his evenings singing in a barbershop quartet, all while still living at home with his doting parents. His life is orderly, small, and quietly desperate for disruption. On Christmas Eve, after performing at a local pub, Colin catches sight of Ray (Skarsgård), an impossibly handsome, emotionally opaque biker. Ray barely acknowledges his existence, then, later, slips him his number. Their first date is a fumbling back-alley blowjob and boot-licking the following evening, which quickly gives way to a formal dom-sub arrangement. Colin moves in with Ray, cooks his meals, sleeps on the floor at the foot of his bed, and follows the rules—occasionally rewarded with wrestling matches in an assless singlet or a joyride with their biker gang. For a while, it works.

Critics have praised the newly released “dom-com” as a rejoinder to last year’s Babygirl, or as the movie Fifty Shades of Grey could have been. Explicit without being sensational, Pillion is as attentive to the power dynamics of transgressive relationships as to the textures of leather and chains. What begins as an unquestioned arrangement (there is pointedly no discussion of safewords or boundaries between Colin and Ray) gradually reveals itself as a coming-of-age story about desire and agency. As Colin navigates this new relationship, the film captures how familiar the imbalance can feel even outside the language of kink: Who hasn’t felt excited, relieved even, by being told what to do? Who hasn’t wondered whether they deserve that attention, and how long it can last?

If you’ve already taken the Pillion ride and want to unpack exactly where you got off, we’ve compiled some helpful contextual notes to decode your experience—as well as further viewing suggestions—below.

1. It’s based on a book that lives almost entirely inside someone’s head

Pillion is adapted from Box Hill by Adam Mars-Jones, a 2020 novella cheekily subtitled A Story of Low Self-Esteem. Written in an intensely specific first-person voice, the book is so interior and self-lacerating that some readers assumed it was autobiographical. Much of its power comes from Colin’s rose-tinted rationalizations—events that might read as humiliating or alarming are filtered through a narrator determined to see them as love. Lighton makes a number of changes, compressing a six-year relationship into a few months and moving the story from the 1970s to the present, which means that Colin’s parents are less opposed to his attraction to men, than they are concerned with his attraction to this specific man, who treats their son like a doormat.

2. Movies like Secretary and The Duke of Burgundy were anti-references

Films like Secretary and The Duke of Burgundy loom large over any conversation about kink on screen, but Pillion defines itself partly in opposition to them. Those movies flirt with irony, camp, and stylization, allowing the audience a certain distance from the power dynamics at play. Pillion doesn’t offer that escape hatch. While there are moments of humor (much of it wrung from the sheer visual differences between Melling and Skarsgård), they’re rooted in realism rather than satire. The film treats its characters’ desires without winking at the viewer, resisting both sensationalism and cynicism.

3. An alarm clock becomes a BDSM toy

Authority shows up in even the most minute details of Colin and Ray’s relationship. Ray keeps an old-school, battery-operated alarm clock outside the bedroom, setting it to wake Colin bright and early. It’s a throwaway decision that actually explains a lot. This is someone who doesn’t just dominate sexually—he’s timemaxxing, organizing his environment to eliminate distraction (and excess emotion) entirely. By the end of the film, Ray’s authority and the clock no longer dictate Colin’s world. The lyrics of the Alessi Brothers’ “Seabird,” playing over the credits, underscore his moving on: “Like an unwound clock / You just don’t seem to care.”

4. It unintentionally references Call Me By Your Name

As Vinegar Syndrome film-distributor Justin LaLiberty memorably put it, Pillion is “Call Me By Your Name for people who really wanted him to eat the peach.” But the connection to Luca Guadagnino’s coming-of-age classic doesn’t end there. Pillion’s final images—Colin crying in a car while the relationship flashes before his eyes—inevitably recall Timothée Chalamet in the closing moments. Lighton has said the parallel wasn’t intentional, but that it became apparent in the edit.

5. A Scissor Sisters cameo will feel like a cultural shortcut for millennial British gays

Jake Shears, frontman of the “era-defining pop disruptors” Scissor Sisters and a cult queer figure with a deep U.K. fan base, appears as Kevin, a fellow member of the biker gang who shakes up his sense of what’s possible in a dom-sub relationship. His casting does more than add a knowing Easter egg: It situates Pillion within a lineage of sex-positive, pop-fluent queer culture.

6. The biker trope is updated for this century

In preparing for the role, Skarsgård tapped into the homoerotic charge of Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising. The avant-garde touchstone from 1963 traffics in a now-classic denim-and-studded-leather iconography of the biker subculture—a Marlboro masculinity that borrows from Marlon Brando in The Wild One as well as Tom of Finland. Pillion has an entirely different aesthetic that updates that lineage rather than replicating it. Ray’s look is sleeker, more controlled—a white leather racing suit molded to his body.

7. It features the least sexy book possible

Of course, Ray is reading Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle—hardly the stuff of erotic fantasy. The Norwegian writer’s hyper-detailed autobiographical series famously chronicles the minutiae of everyday life (laundry, stoplights, awkward social moments) as well as longing and despair. In Pillion, the joke isn’t just the appearance of this marker of literary taste—it’s that Ray is largely unknowable, keeping his feelings and personal history under wraps. Reading My Struggle situates him as a real person with his own internal preoccupations and potential obsessions. Colin eventually gets his own copy, grounding the couple’s romance in the ordinariness of their shared life (dom-sub couples like to read before bed, just like us!), but more importantly, his joining the Knausgård’s train signals that he’s chosen to enter Ray’s world, too.

What to watch next

- The Wild One (1953, available to stream on the Roku Channel): Marlon Brando plays the archetypal rebel biker in this flick about two rival gangs

- Scorpio Rising (1963, available to stream on YouTube): Kenneth Anger’s seminal avant-garde short, blending homoerotic biker imagery with pop and religious iconography

- Secretary (2002, available to stream on Tubi, the Roku Channel): A cult classic about a young woman entering a BDSM dynamic with her boss, starring Maggie Gyllenhaal and James Spader.

- The Duke of Burgundy (2014, available to stream on Tubi, Mubi, the Roku Channel, AMC+): A hypnotic study of a lesbian BDSM dynamic in a lushly composed domestic setting.

- Please Baby Please (2022, available to stream on Amazon Prime Video, Tubi): Harry Melling’s earlier foray into on-screen roleplay, opposite Andrea Riseborough, in a deliciously camp musical about a bohemian couple spicing up their sex life.

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

Tessa Thompson Took Two Years Out of the Spotlight. This Winter, She’s Back With a Vengeance.

On the Ground at Art Basel Qatar: 84 Booths, a Sprinkle of Sales, and One Place to Drink

How to Nail Your Wellness Routine, According to American Ballet Theater Dancers

10 of New York’s Best-Dressed Residents Offer the Ultimate Guide to Shopping Vintage in the City

Sign up for our newsletter here to get these stories direct to your inbox.

in your life?

in your life?