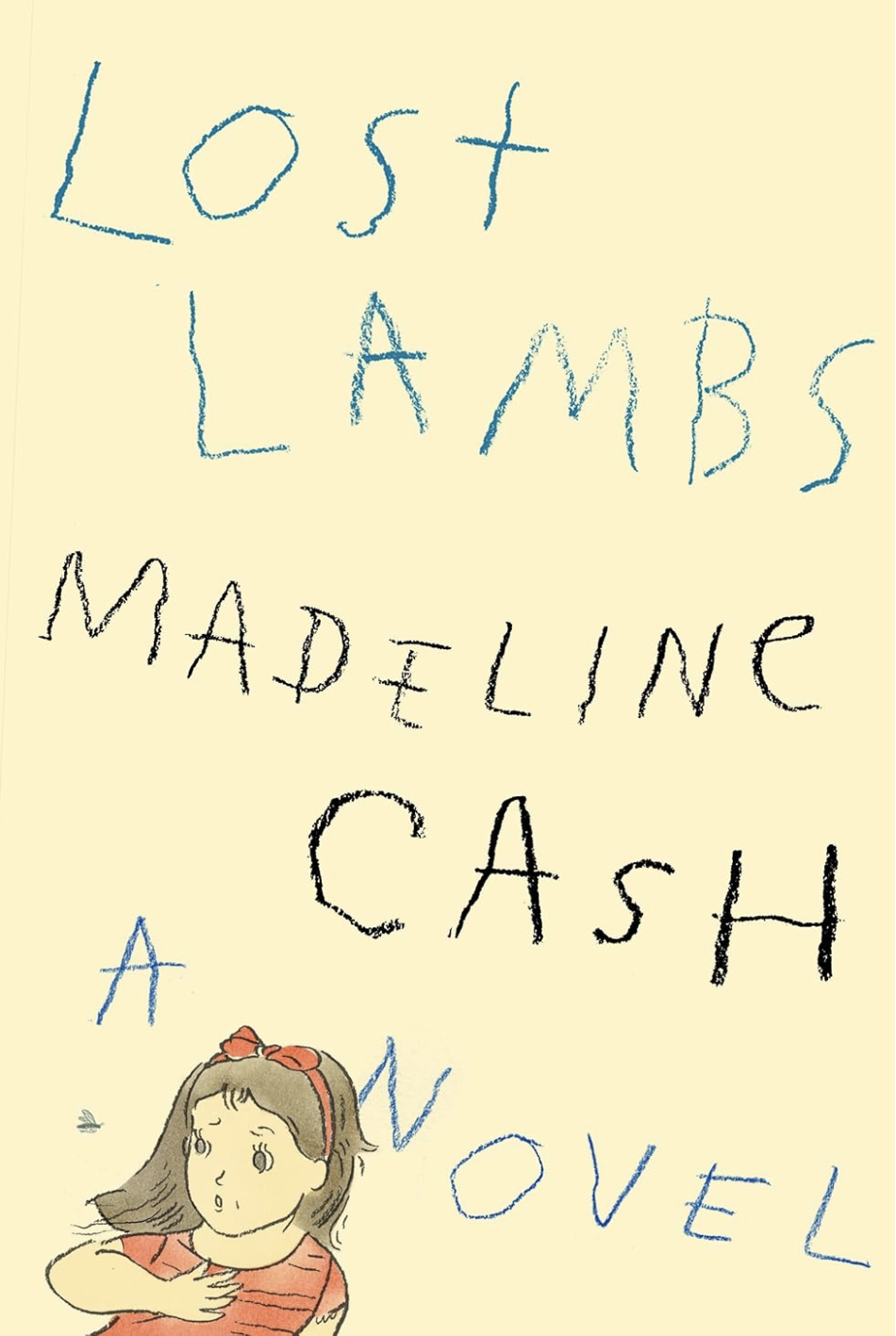

A trinity of teenage girls in Genesis drag (i.e., dressed like the animals on Noah’s ark) share a cigarette in an unnamed suburb of a nameless city. This lion, fox, and hedgehog are playing hooky—skipping out on their Church production of a Biblical fable in search of some adolescent grandeur of their own. The youngest is “incredibly, painfully, mythically bored,” a precocious “troublemaker with no origin myth” intent on seeking one out fast. The middle sister, less bored and more boring, is trapped in “a prison of her own mundanity,” while the eldest is a vaguely anorexic romantic who muses that “having less of her to hold forced people to find more of her to love.”

These are the Flynn sisters—daughters of Bud and Catherine, whose freshly opened marriage is less a new horizon of thrilling potential than an open wound wreaking havoc on their their church community, children’s psyches, and the sinister schemes of a spectral local billionaire (think Epstein’s criminal cunning tinged with Thiel’s hankering for immortality). Those are just a few of the lost lambs who traverse the uncanny terrain of the so-titled debut novel from Madeline Cash. Lost Lambs’s ensemble cast also includes a rumored war criminal-turned-security guard, a beleaguered support group leader, and an enervated pastor struggling with an existentially sick flock and a gnat-infested church knave. These wandering souls are yearning for answers: delving into online conspiracy theories, entering “Inner Beauty” pageants, hiring private investigators, and asking to speak to the manager in the search for direction.

At 29 years old, Cash straddles the Gen-Z-millennial cusp—she believes Internet doomsdayers aren’t thinking creatively or communally enough. Technology, rather than a harbinger of the apocalypse, “can actually bring us back towards collectivism,” she has noted. An erstwhile Dimes Square denizen who recently decamped to London, Cash is also the author of the 2023 short story collection Earth Angel and the co-founder and former co-editrix of Forever magazine. Earth Angel’s digitized landscape, dense with the detritus of early Gen Z girlhood, is infused with the garish aughts-era internet aesthetic that Forever so deftly encapsulates: calorie counting, fake friends, biblical plagues, bad boyfriends, worse bosses, and gullible mothers.

Decades after the turn-of-the-century heyday of hysterical realism, Cash may be pioneering a new mode for this moment: Call it optimism-pilled manic-pixie-paranoid-realism spiced with the sacred. If that sounds like a mouthful, it’s only because this book is as invested in a zany, zigzagging lucidity as it is in pithy, parodic zingers. 5G and Web3 promise opportunities more than just doomscrolling. In Cash’s fictional town, young lovers lie in pesticide-drenched grass and play “star or satellite.”

Contemporary fiction often documents neoliberal ennui through depressive, digressive, time-stamped autofiction. Yet a soft-spoken, observational voice pervades many of these accounts-cum-indictments of capitalism’s hyper-individualistic ethos. Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection, last year’s delicate but scathing portrait of millennial malaise, dealt in what writer Alice Gregory described as “supposedly-quiet-but-actually-quite-loud cultural signifiers of intellectualized upward mobility”: “houseplants, hardwood floors, unread back issues” of The New Yorker.

In Lost Lambs, Cash declines to tell us where, let alone when, we are—inventing a fictional universe devoid of “proper nouns,” she told me. Rather than simply condemn modernity for atomizing us, she offers an alternative vision of collectivity: refusing her readers a protagonist and offering us an eccentric troupe of players instead. Whether they’re competing in a game of life or staging a performance is up to you; in either case, their madcap hijinks require banding together, and a new approach to being part of a community.

Let’s take Bud—the Flynn girls’ father—for example. He begins the book underwater: disconnected from himself and overwhelmed by the deluge of words and need flowing from his wife and daughters. He is disturbed by the “near-constant bloodstream from these women—noses, knees, elsewhere.” But by the book’s final pages, the bemused patriarch is at the helm of a family that has become one beating, pulsing heart, spreading bizarre and heartwarming vibes throughout town. Once-ominous symbols re-surface as routes to catharsis and maligned markers of hyper-modernity are transmuted into symbols of possibility: a mysterious mercenary reveals a heart of gold, a polycule inspires a proto-incel to crawl out of his shell, and an internet-fueled conspiracy theory sparks a rescue mission for human trafficking victims that results in more pizza party than pizzagate.

Ahead of Lost Lambs’s release earlier this month, Cash and I met, fittingly, on the outskirts of Dimes Square to discuss religion, vindicated paranoia, retaining optimism against all odds, and maintaining a healthy relationship with your phone.

You wrote a thick, sprawling family novel in an era dominated by slim tomes of autofiction. It reads as both hyper-contemporary and nostalgic, almost like a traditional family novel written by someone steeped in the narrative structure of multi-player video games.

There’s absolutely a rejection of autofiction, which I came up on. I am grateful to that era, but I must respectfully graduate. After Earth Angel, I wanted to write a complete work of fiction. I swung the pendulum so far in the other direction: the novel has no proper nouns. Everything is made up, from the names of medications to the names of dinosaurs. I also love a hardy family novel. It feels like a very masculine thing to write, and I’m very contrarian. I want to do what I’m told not to do.

You’ve critiqued our culture’s addiction to individualism elsewhere. Was the book’s ensemble cast, its lack of a singular protagonist, perhaps rooted in that critique? Autofiction often indicts our culture’s individualism in a nihilistic, resigned style; might your collective of protagonists offer an actual alternative to pure individualism?

Definitely. As an amalgamation, the characters in this book almost equate to one well-rounded human being, but individually, they’re archetypes. There is no hierarchy: No one is better or more interesting than anyone else.

There’s a strong religious current running through this book as well as Earth Angel. You write in a mythic, fable-coded register that is drenched in wit. Is this intended as a humorous origin tale for our ostensibly godless era?

I attended Lutheran elementary and middle school, and did not realize the impact that education had on my psyche. I thought everyone grew up with institutional religion, but that’s not the case. People often say there are a lot of religious themes in my work, but there are a lot of religious themes in life. It is the origin of all morality, and the book needed a good moral springboard.

The religious elements felt related to the presence of animals throughout. Both your books open with animal crises connected to religion getting “out of hand”: the gnats in the church in Lost Lambs, and the frog plague in Earth Angel.

Totally, it’s a little Noah’s Ark. Earth Angel walked so that Lost Lambs could run—it grew out of that book, which was the first thing I’d ever written, when I was 23. Those themes have interested me for a decade now.

I have to ask about the gnat-based wordplay—throughout most of the novel, any word that includes the letters ‘nat’ consecutively has an added g before the n, starting from page 1, with ‘extermignated.’

It’s a grammatical conceit in the book. The text is infested, as is the town. When the gnats are exterminated from the text, they are exterminated from the town. I wanted there to be an invasive element to reading the book that was visceral and felt. The gnats represent the sense that something is not right, something needs to be fixed, and they are a continuous disturbance until they’re not.

The women and girls in this book understand extreme frailty as both an alluring accessory and a suit of armor in a world that’s clearly designed to hinder their thriving, to understate the case. How does the emaciated beauty ideal function in this book?

It’s rooted in how I perceived “beauty” to work growing up: the currency of your youth and beauty was ephemeral, but also the most important thing you had as a woman. Since everything in the book is quite hyperbolic, I leaned into that. Where the men fear dying, the women fear aging. I see that in my mom. It’s unintentionally bestowed on us.

Sisterhood in the book is stretchy, opaque, and unpredictable—the Flynn girls not necessarily intimate or friendly in the ways a reader might expect, but they risk everything for each other. What were you aiming to reveal through their relationships?

I don’t have siblings myself, but I was brought up with an it takes a village to raise a child mentality by my mom’s friends, teachers, and people she plays mahjong with. Maybe the person you expect to be omnipresent is not always around, but when push comes to shove, they’re there for you. The sisters I initially imagined as one character splintered into three. Like the Holy Trinity—Father, Son, Holy Spirit—they are different elements that kind of equate to one person. As they grow up, I think they’ll flesh out.

The novel is written in a complicated tone—a sort of mournful satire, hopeful parody mode. You’re really funny, so I’d love to hear you talk about how humor functions here.

It’s probably a defense mechanism. [Laughs.] One of the main notes from my editor was to balance humor with sincerity a bit more. One of the characters, who is at times a mouthpiece for me, says, “You can speak truth to power if you’re doing it under the guise of performance and humor.” It’s really hard to write a book about human trafficking, terrorism, and aging, but humor allows you to do that.

Your work often feels like it’s about finding the beauty in the 5G-infused air. The novel is also a polemic about surveillance technology without actually relying too much on it from a plot perspective. You titrated the actual use of technology—the characters are rarely on their phones.

I really don’t like writing about technology. It was very intentional to not use any proper nouns relating to the tech sector. Also, I have a pretty healthy relationship with my phone. Everyone talks about wanting a flip phone these days, and I’m like, That sounds bad. I like using my maps and listening to music.

Your characters operate in a paranoid mode, like many of us do today, but one that seems clarifying, perhaps even empowering, not symptomatic or delusional?

I wanted [the book] to say: Nothing is a coincidence, where there’s smoke there’s fire. Every hunch that a character has turns out to be valid. I took a class in college on paranoia that was called “You’re So Paranoid You Probably Think This Class Is About You.”

There’s a point where a minor character—a potential future gooner or manosphere denizen—observes the main characters, a family-cum-polycule, having a great time at a restaurant, and wants to join them. What were you implying about the ways out of a masculinity crisis-coded mindset?

There is light. It’s so easy to slip into our basest, darkest instincts, but if you’re not alone, you don’t have to give in to those.

What were you reading while writing this? What were your influences, direct or ambient?

To plot out the mystery, I read a lot of hard-boiled noir detective books from the 30s, 40s, and 50s—like The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon. I watched The Long Goodbye. I love Jonathan Franzen, quite honestly, he’s the master of the family saga. And systems novels that use the plot as a parable to critique our social or political systems: Don DeLillo and Joseph Heller. Henry Darger’s painting Vivian Girls, which depicts little girls in flight, feels thematically relevant. CULTURED readers, it’s in the MoMA if you want to go see it. Lydia Millet’s The Children’s Bible is really important to me; it’s a great parable, if a little on the nose.

What are you finding underrated in our culture these days?

Drinking a glass of milk.

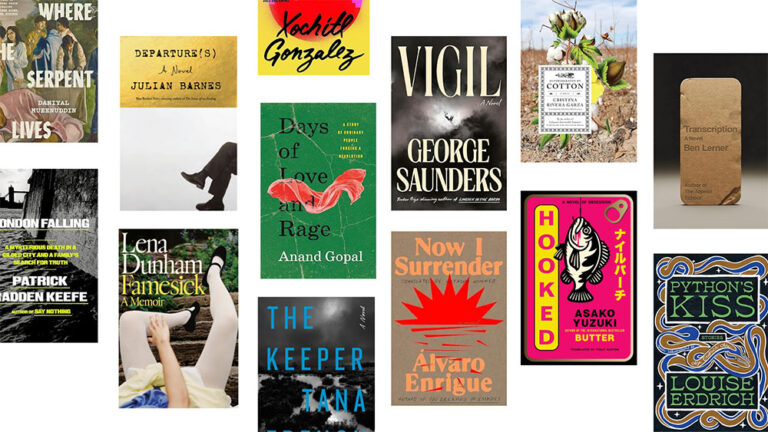

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

13 Books Our Editors Can’t Wait to Read This Season

With Art Basel Qatar, Wael Shawky Is Betting on Artists Over Sales Logic

Jay Duplass Breaks Down the New Rules For Making Indie Movies in 2026

How Growing Up Inside Her Father’s Living Sculpture Trained This Collector’s Eye

It’s Officially Freezing Outside. Samah Dada Has a Few Recipes Guaranteed to Soothe the Cold.

in your life?

in your life?