We all handle grief in our own ways, but few do so more singularly than Helen Macdonald, a writer and naturalist who found respite after the death of their father by devoting themself to the care and training of a goshawk.

This week, English director Philippa Lowthorpe is releasing H is for Hawk, an adaptation of Macdonald’s memoir starring Claire Foy as Helen, Brendan Gleeson as Helen’s father Alisdair, and a stable of winged performers in the role of Mabel the hawk, who soars through the woods in some of the most arresting wildlife footage seen outside the BBC.

When she’s not in the air, Mabel is holed up at her handler’s home, one half of a codependent relationship that seems to alternately serve and hinder both parties’ growth. Lowthorpe—known for her work on the series Five Daughters, The Crown, and Call the Midwife—moves between each pole with practiced ease, interspersed with clips of Gleeson’s many warm moments with his onscreen daughter, highlighting the gaping void of his absence.

Ahead of the film’s release, Lowthorpe sat down with CULTURED for a look behind the scenes at working with a fleet of avian actors and an exploration of the cast and crew’s personal connection to Macdonald’s story.

CULTURED: How did you come to this project?

Philippa Lowthorpe: I did a show for the BBC called Three Girls, which was a really tough subject about the grooming gangs in Rochdale in the north of England, and it caused quite a big stir in this country. Dede Gardner [and Lena Headey, the producers] got to watch it, so then they invited me to pitch for directing [H is for Hawk]. My dad hadn’t long died before I had this phone call from them, and so when I read [screenwriter Emma Donoghue’s] first draft of the script and the book, I found it so overwhelmingly moving. It really spoke to me in such a deep way about not only grief, but about a very good father and daughter relationship.

We don’t see many father and daughter relationships that are good. We see dysfunctional ones, don’t we? But a proper adult relationship between a grown-up daughter and their father that is very positive and affirming and loving and funny, we just don’t see that. I’m one of three girls and we had a dad who was also a bit of a character, like Helen’s dad. It just seemed such an extraordinary story. But there’s also the challenge of filming a hawk and bringing that into this film, so it’s not just a character study. It’s got this other incredible dimension of a woman’s obsession. And the other thing is, we don’t often see very clever women in film, do we?

CULTURED: Did you get the chance to talk to Helen about the book?

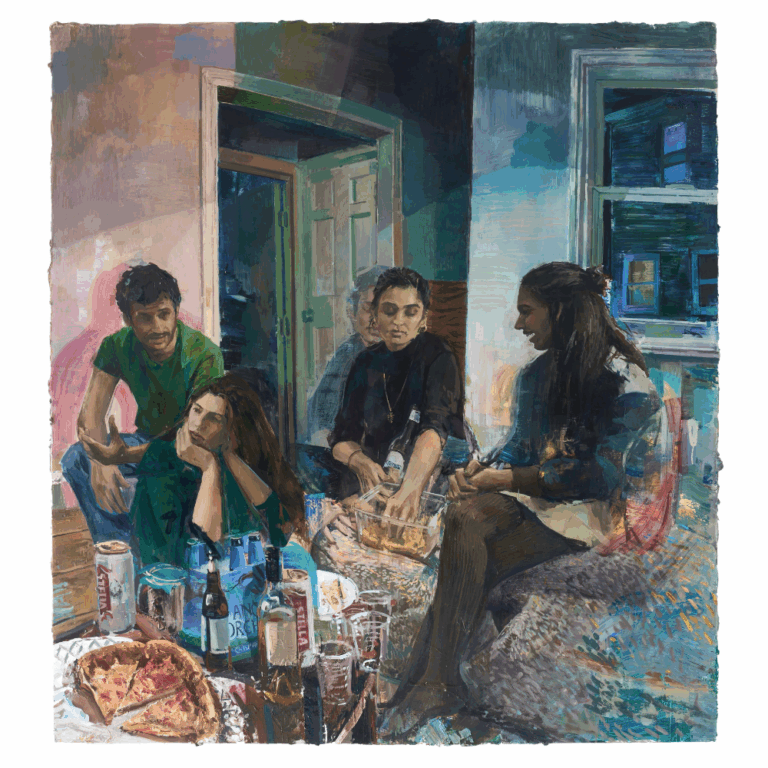

Lowthorpe: Helen, right from the beginning, was so collaborative, so helpful, reading drafts of the script, giving advice about falconry, giving us the idea of contacting Lloyd and Rose Buck, who became our hawk experts. Claire had to learn falconry, and Helen was involved in every detail. Because it was a very low budget film, we had to find lots of different ways of set decorating. Sarah Finley, our brilliant designer, asked for Helen’s email to check on things, like, what did her house look like? Helen said, “I’m gonna lend you all my treasures.” So we had Helen’s pictures, feathers, little skulls. Helen and their family came to the filming, and Helen’s mom sat on the sofa in our set and said, “This feels like home.”

CULTURED: How did Claire and Brendan join the project?

Lowthorpe: I’d worked with Claire, because I directed some of The Crown. She is so charismatic and so watchable. Claire read the script and said yes straight away. And then Brendan, we needed somebody very charismatic to play her father and somebody who can really hold the screen. He agreed to read the script and then I was sitting in this very seat, February last year. I felt like he was interviewing me rather than the other way around. He was asking lots of questions about how I like filming and what the meaning of the story was to me. I told him about my dad. And because he’s also a dad, even though he hasn’t got daughters, he was very, very interested in that idea of being a good man.

I know because I have a son as well, there’s a lot of negativity about men around. It’s quite nice to be able to show something that’s positive. Even though he was quite dysfunctional, her dad in lots of ways had lots of funny, crazy obsessions and he understood his daughter in such a profound way. Brendan really loved that idea. He actually was talking to me about bringing up his sons and saying that had been really concerning to him, so much negativity towards them. I ended up crying at something he said because it was so moving, and he said, “I’ll do it for you, Philippa. Count me in.” I’m sure it’s because I wept.

CULTURED: Oh, dear.

Lowthorpe: Brendan’s very funny and very naughty. When we were doing one of the scenes [where] he’s sawing the branches of the tree. He’s doing some trimming in the garden and he got so carried away. The people whose garden it was said that we could just take a little bit off. He was so enjoying himself, he sawed half the tree off. But then he looks directly into the camera as if to say, “I’m being naughty.”

CULTURED: I was dying to ask you about having a hawk as one of your lead actors. How did you pull that off?

Lowthorpe: We were very, very lucky that we had fantastic bird experts who live near me in Bristol where a lot of natural history filming gets made—all the David Attenborough and that stuff. Lloyd happened to be an expert in goshawks, who are the most difficult hawks to train. He had trained two of his hawks [to] do the hunting scenes as stunt doubles, like in the Bourne films when you have the stunt double for Jason Bourne. Lloyd had trained them to fly with these little tiny drones next to them and also to work with a fantastic wildlife cameraman called Mark Payne-Gill. He goes off to South Africa to film turtles or whatever, but he’s brilliant at filming birds. It’s like a military operation filming those scenes.

For the interior scenes, we have two sisters called Mabel 1 and Mabel 2. They looked identical, but they had quite different personalities. We had five hawks altogether [including] Jess, who came all the way down from Scotland to live with Lloyd for those months while we were filming. Jess is the hawk that does all the playing.

CULTURED: I imagine it creates a different energy on set to have this animal.

Lowthorpe: Everything was organized around the hawks—everything. All the crew were told to wear, as Lloyd said, plumage. We had to wear all dark colors. If you had bright green trainers on, you were sent off. When the hawks came on set, everybody had to hide. In those interior scenes, I was hiding behind a piece of furniture with my little monitor whispering things. Charlotte [Bruus Christensen, the director of photography] was in there, and she has beautiful blonde hair and Lloyd made her wrap her hair up in a cap. She had to wear the same cap every day because Lloyd said goshawks are very skittish. They didn’t like any change. So we all had to wear the same clothes. And Claire had to do a crash course in falconry before we started. Lloyd created a dummy camera with an easy rig and went around for at least three months before we filmed wearing that easy rig all the time just to get them used to a strange object. They really don’t like booms, the fluffy thing on the end of the sound pole. All the cameras had to be hidden all the time, little tiny microphones, behind a vase or somewhere.

CULTURED: And you told me director Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colors: Blue had a big influence on the film?

Lowthorpe: What really attracted Charlotte and me to that film was the intimacy of the camera with Juliette Binoche. It’s a film about grief and the protagonist has the camera on her nearly all the time. We knew that our film would also have that. That intimacy with the camera, and the compassion of the camera to the female character, is something we really was important to us. Weirdly, we were both collecting references separately and we both came up with that.

Claire is such a fine actress. Everything is on her face in such subtle detail. In the beginning, when she answers the phone and learns her dad has died, she goes over to the fireplace and puts her head down, and she’s just in silhouette. You see a little tear. That’s one of my favorite shots in the whole film; it says so much about using light and shadow to chart an emotional journey. That’s what Krzysztof Kieślowski does brilliantly.

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

Why Are So Many Contemporary Museums Showing Dead Artists Right Now?

Wolfgang Tillmans Became a Household Name Finding Beauty in the Banal. He’s Ready to Re-Evaluate.

19 Design Experts Answer All Your Burning Interiors Questions

Nia DaCosta and Ryan Coogler Compare Notes on Marvel, Genre-Hopping, and Making Films That Shock

in your life?

in your life?