Do all roads lead back to the nude? I want to say no, but I also kind of love that my four-day trip to Poland in November is, in some sense, thematized by that forever fraught thing: the female figure. Your body is a battleground and—socially, politically, visually, art historically speaking—it has been for at least 500 years.

In a span of 12 hours, I stand before two works by Lisa Yuskavage, on two continents. In New York, at the Morgan Library, it’s Piggyback Ride, 2009, a charcoal drawing featuring one nubile girl carrying another through a sooty, flooded wasteland. For a semi-public streaming event in conjunction with her solo show there, Lisa and I talk about line and color in front of it. I think of Piggyback as a tenderly pornified picture of solidarity, its melancholic eroticism speaking to the loneliness or ambivalent pleasure of objectification, the so-called male gaze as an environment rather than a vantage, a kind of radioactive fallout, existing without, maybe long after, men.

Seems like an appropriate image to dwell on, I think, as I roll my suitcase out onto the street. I’m on my way to Warsaw at the invitation of curator Alison M. Gingeras for the opening of the major survey of women artists that she’s organized at the Museum of Modern Art (MSN Warsaw). “The Woman Question 1550–2025,” as it’s titled, is among the institution’s momentous first three non-collection exhibitions in its new building since its grand opening early last year, after operating for two decades without a permanent home.

Even on paper, Gingeras’s show is an impressively unreasonable undertaking, with a go-for-broke artist list, including marquee attractions (Artemisia Gentileschi, Tamara de Lempicka, Frida Kahlo), feminist mainstays (Yoko Ono, Maria Lassnig, Faith Ringgold, Mary Kelly, Lubaina Himid, Barbara Hammer), and no shortage of perspectives from younger generations. In this last category, Clarity Haynes, Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo/Puppies Puppies, Jordan Casteel, and Aneta Grzeszykowska are among the many names I recognize, though it’s the unfamiliar ones here—from every era—that constitute the real story of “The Woman Question.” The exhibition “challenges the notion that women were largely absent from art before the late 1800s,” per the online press text. “The result is a collection of nearly 200 works, including paintings by Renaissance, Baroque, and 19th-century women artists through more contemporary works, offering a centuries-long visual history of women’s ‘emancipation.’”

It’s funny now to think that I almost didn’t go. I missed the initial email. Then, my fall was so busy, it seemed crazy to go to Warsaw right before Thanksgiving. But I ran my eyes over the artist list a few times, wondering about the dozens of Eastern European names I knew nothing about, and I realized it would be crazy not to go. (Perhaps emancipation in scare quotes sealed the deal for me.)

It feels glamorous to leave straight from the Morgan for the airport, less glamorous to spend eight cramped hours in economy on an overnight flight, reading through the exhibition materials and the articles I’ve bookmarked on Polish politics. In a nutshell, in case you don’t know: The far-right, Roman Catholic Church-aligned Law and Justice party (PiS)—though ostensibly ousted from power by the formation of a centrist coalition government in 2023—maintains a stranglehold on legislation via a fascist president with veto power and a constitutional court corrupted by nearly a decade of party rule. Cultural institutions and national media struggle to recover their legitimacy after becoming mouthpieces for PiS propaganda. And the upshot of the All-Poland Women’s Strike? The national mass movement that flooded the streets with protestors under the sign of a red lightning bolt in 2020-21, electrifying the world with its fury and commitment? Abortion remains generally illegal in Poland (though barriers to access are lax relative to, say, Texas).

When I finally arrive at the hotel, I’m almost due at the museum, but I lie down in the beautiful room, order soup and cake from room service, and wonder why go to the press preview when I can just go to the party later? I rest and set out for the museum as the sky grows dark, winding through a park and then down wide streets, veering off course to walk through the vast, almost empty grounds of the Saxon Palace, destroyed during WW2. Intrigued by the torchlight beneath the remaining block of neoclassical arches—the eternal flame, I realize in a moment—I watch, from a good distance, the changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Soon, I reach Marszalkowska Street and see the museum, a sparkling white boxy structure standing in the shadow (so to speak) of the Palace of Culture and Science—the hulking, ornate skyscraper, built by Stalin in the 1950s as a gift to the Polish people at the edge of the former site of the Warsaw Ghetto.

I stand in the cold watching a billboard-scale slideshow projected on the side of the new museum. The first image, though its text has been translated into Polish, is instantly recognizable, with its gorilla-masked Grande Odalisque, as the Guerrilla Girls’s 1989 poster Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?

They don’t have to be naked to get into MSN Warsaw, but there are an awful lot of naked women inside. I find the Yuskavage painting on my first quick circuit of the galleries and text Lisa a photo of her Bedheads, 2018, in context, as promised. The picture, with its palette of shamrock, margarita, Lemonhead, and rose-peach, captures a man pulling his pants off in the foreground, while a 1970s Penthouse/Renaissance Olympia shares a look with the viewer, her arm held out (to snap a selfie?). It comes last in a hot, intergenerational sequence of three canvases. Joan Semmel’s Green Field, 1992, showing entwined bodies in a malachite dream, is first; then comes Ambera Wellmann’s In media res, 2019, a vignette of blurred lesbian hardcore on a drift of pink.

The works appear in the section focused on women’s erotic imagination (titled “No Gate, no Lock, No Bolt”), which is perhaps not surprisingly particularly lush. But, in truth, the entire exhibition is high-key, seductive, profoundly accessible in its commitment to figuration and variety, and guided by pop—or punk—savvy. The film 3 Minute Scream, 1977, by Gina Birch (of the Raincoats!), which very simply and ingeniously features the artist screaming for the duration of a Super 8mm cartridge, is the welcoming cri de coeur, looping at the entrance.

In the small room, capacity 10, where Gentileschi’s Susanna and the Elders, 1610, is on view (visitors queue to get in), the proximity of a 2013 film by Chiara Fumai, for which the artist reads aloud from SCUM Manifesto (Valerie Solanas’s 1967 argument for the elimination of the male sex), makes the vivid polemic a soundtrack for the Baroque painter’s bible scene. The visceral disgust in the then 16-year-old Gentileschi’s depiction of the lecherous elders, attempting to extort sex from the bathing Susanna, syncs well with Solanas, establishing an all-too-credible transhistorical through line in this story of feminism avant la lettre: rage. (The next night, walking to dinner with Julia Bryan-Wilson, curator of the excellent “Gutsy,” a 12-artist, largely abstract endeavor in the museum’s concurrent “City of Women” constellation of shows, tells me that, during the press preview, she spoke with the lender of Susanna, Dr. Damiana Gräfin von Schönborn-Wiesentheid, whose family has cared for it for centuries. She referred to the Gentileschi’s work as simply The Painting. I find that funny, of course, but it also makes me realize how strange and special this presentation of it really is.)

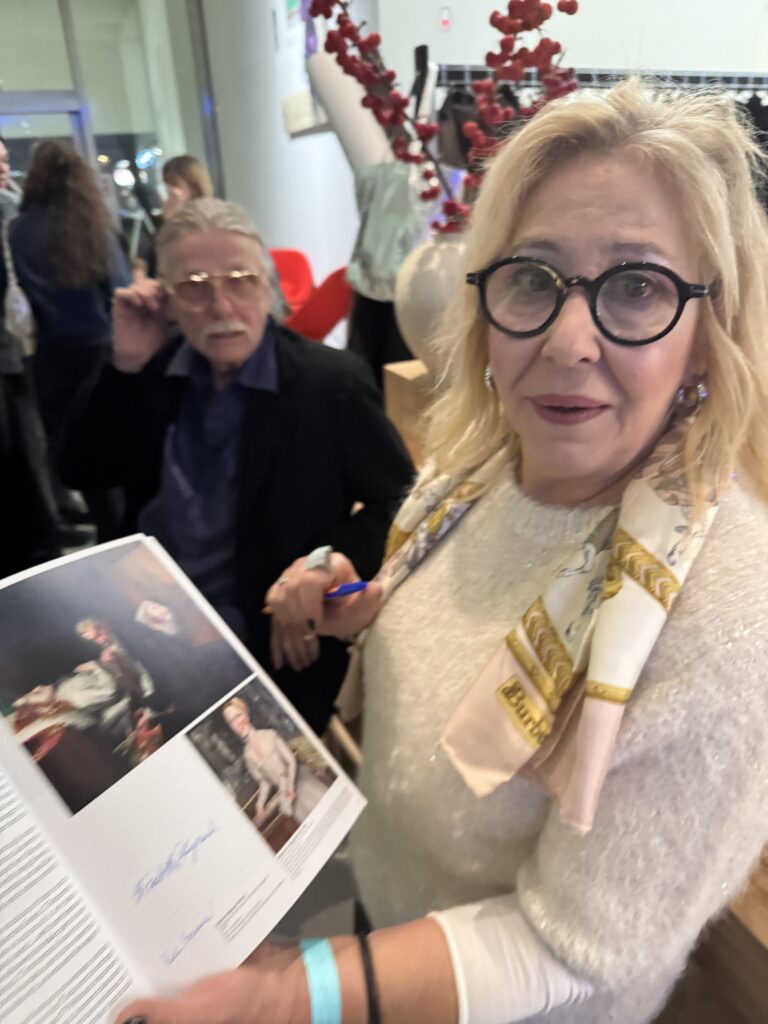

At the opening party, I don’t mind the vertiginous sense of time and geography contracting and dilating, heightened by both jet lag and this massive, international, unchronologically-ordered show. It’s fun. I look for Józefina, the museum’s communications director, who has arranged my travel—she’s texted me that she’s six-foot-two and wearing a magenta jumpsuit, so I find her quickly. I thank her profusely for everything, and though she must be exhausted, she begins to reel off insider tips about where I should go during my visit. When I can barely stand anymore, I text Alison to congratulate her, and then go to find her in the bar to say it in person. I have a drink with New York artist Scott Covert and Italian painter Elisabetta Zangrandi, who opens the catalogue to show me her work in the show. (Alison tells me she’s going to take Scott, whose art is based on gravestone rubbings, to Lodz later in the week to capture the headstone of Wojciech Frykowski, murdered by Charles Manson.)

It’s on subsequent visits to the exhibition—I return to the museum every evening I’m in Warsaw—that I’m able to see how exactly it “challenges the notion that women were largely absent from art before the late 1800s,” i.e. in thrilling new scholarship regarding the identity of the Netherlandish Renaissance painter known as the Brunswick Monogrammist, highlighted in the “Anonymous Was a Woman” section. (The show argues that a 16th-century Ecce Homo painting was made by the woman artist Mayken Verhulst.) But, in a way, that’s the least of it. Throughout the galleries, there are surprising works—”discoveries” for me—attesting to women’s continual artistic work (and periodic erasure). Both the inclusion of lesser-known modern artists who slipped from view during the upheaval and destruction of the 20th century and the integration of self-taught and folk artists feel exciting and invaluable.

As does the “Wartime Women” section, which focuses on WW2, the Holocaust, and contemporary Ukraine. A more constrained timeline and Eastern European regional focus allow for concrete, historical connections between artists to emerge (and I’m embarrassed to admit that I didn’t know about any of this work before). Here, artist-witnesses to different, but not distant, genocides mingle, as do their disparate images of valor and indignation. Ukrainian painter Kateryna Lysovenko’s 2022 image of a statue-like mother and child brandishing their middle fingers joins Roma artist Ceija Stojka’s depictions of Nazi concentration camps and Zuzanna Hertzberg’s sewn banners of Jewish-Polish antifascist fighters.

In the morning, I walk around, buy a toothbrush at a liquor store, and get in touch with the American artist Carmen Winant, who’s also in Warsaw, to see if she wants to hang out before her talk at the museum the next day. In a sense, spatially, her monumental piece The last safe abortion, 2023–, is the centerpiece of MSN Warsaw right now. Included in the show “Her Heart,” curated by Karolina Gembara (also a part of “City of Women”), Carmen’s sweeping grid of some 2,500 archival photos—showing the daily work of abortion clinics during the nearly five decades when Roe v. Wade was settled law in United States—occupies an atrium wall, visible from every floor of the museum as well as its grand zigzagging central staircase.

Stacked prints of images from the Women’s Strike protests, shot 2019–2021, produced in cooperation with the activist-photographers’ collective Archive of Public Protests, are free to take. Showing the drama of the mass street actions by pro-abortion demonstrators, the posters are elegant foils to Carmen’s painstakingly unspectacular requiem to a freedom won by feminist struggle and maintained by women’s labor; an apt way to connect the Polish and American abortion movements, which are united not just in their aims but also, right now, in their terrible disappointments.

Gembara’s curatorial text is searing, seething—not just in her righteous demand for bodily autonomy and her belief in art’s capacity to describe abortion’s reality—but with the bitterness of the politically forsaken. Regarding the recent elections that demoted PiS, she writes, “Many of us believe that it was women’s anger and solidarity that helped push right-wing politicians out of power. Today, we know that no one is going to thank or repay us for that.”

It’s a sentiment echoed in our conversation the next day, when—after catching up over coffee—Carmen and I knock on the door of AboTak, “the first Polish abortion center,” just to… say hello. We had both been reading about the activists, how they use a legal loophole to help abortion-seekers order pills online. Operating out of a storefront, Abotak has a small merch boutique, an information desk, and a lounge where you can pop misoprostol and wait in the company of experienced friends. Located directly across the street from the Polish parliament building, the center is also a kind of taunting rebuke, with its psychedelic Pop-art mural and “fuck for fun” T-shirts.

“Business” is slow. After Carmen and I sheepishly introduce each other as a feminist artist and writer respectively to the three young women working, they bring out coffee and cake and talk with us for an hour or so—about global reproductive rights, Zohran Mamdani, The Silent Scream (the vintage anti-abortion propaganda film they were shown in school), how they met at the protests, how anti-abortion activists throw acid on their door, and blast recordings of babies crying. At least they don’t have guns, the women say, like in the U.S. Carmen invites them to her event later, and they already know about the shows at the museum. (Zuzanna Hertzberg is also an AboTak activist-volunteer.)

In the meantime, I walk back to my hotel, stopping to watch people put Christmas decorations up in a small public square, and then go back to the museum, to spend more time with Julia’s show (the aforementioned “Gutsy”) which—relative to “The Woman Question” and “Her Heart,” anyway—feels moodily restrained, with sculptures by Charlotte Posenenske, Alina Szapocznikow, and Senga Nengudi presiding over the main room. But, during my time in Warsaw, the show’s collective material and formal metaphors for the body’s internal systems of metabolization and regulation—its guts—sink in as another language of urgency. The night before, at dinner, Julia makes the case for the work as a chorus of responses to fascism, or fascisms. I sit next to the Chilean, Berlin- and New York-based Johanna Unzueta whose painstakingly handmade felt “pipes” crawl up the walls; the Palestinian artist Jumana Manna—whose included sculpture uses real, metal pipes—stops by to say hello.

I meet up with Alison briefly for tea at the museum café, and we gossip about New York acquaintances. I’m happy to see Emilia from Abotak there, sitting at the bar drinking a glass of wine, and we walk over to theater together to see Carmen speak. She discusses her work—the mundanity and repetition of reproductive healthcare, the unremarkable office and exam-room backdrops of the photos she has amassed—as a visual counter to the histrionic imagery of the flash-lit fetus, floating in a void (or the more gruesome material used by antis). German-Austrian filmmaker Franzis Kabisch walks us through the desktop video essay Getty Abortions, 2023, a funny-if-only-we-could-laugh index of the melancholic figures, always looking away, that populate the stigmatizing stock imagery used to narrate abortion stories. Talking with the artists and Emilia after, it seems a rare moment, or one not often seen so plainly: the representational concerns of feminist art, presented at a museum, addressing the strategic needs of a movement.

The next day, my last full day, it snows. I had planned to walk around the city’s historic Old Town, whose postwar reconstruction has been explained to me by two Uber drivers, before going to Polin Museum. I wasn’t planning to tour the permanent exhibition there—the 1,000 year history of Polish Jews. I thought I wouldn’t have time, but I do, emerging dazed and devastated from the windowless journey on the bottom level after a couple of hours. From the windows of the Legacy Gallery upstairs, where two small, abstract Szapocznikow sculptures are on view (Vowel and Consonant, both from 1962), I watch snow blanket the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes.

It’s getting dark, but I have more to do: I take a car to the artist-run gallery Turnus, which a few people have mentioned to me when I say I want to know about art—not just major institutions—in Warsaw. I’m dropped off by a small courtyard, with a pizza place and an Indian restaurant, and I figure I’m in the wrong place, but I turn around and I find it. Turnus is a cozy spot, with a café on the ground floor and a group show upstairs. There are no English wall labels for the work, so I pride myself on finding something authentically local—though, of course, it’s also a barrier to my understanding. I watch a great video—a close shot of legs and feet in white tights and Mary Janes squishing in mud—and buy a tie-dyed T-shirt printed with an image of a tiny kitten on a saucer with a cappuccino and a cigarette. My sense is that this souvenir captures something essential.

I can’t believe my day—now night—doesn’t stop here, but I keep going. I return one last time to the museum. I stand outside for a while, trying to take a good picture of the Palace of Culture and Science across the Plac Defilad, the snow rendering every Warsaw scene extra cinematic. Then, I revisit the third floor, which hosts “Near East, Far West,” the main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial. It would be another 2,500 words, at least, about another sprawling import group show, so I’ll save writing about it for later. I take one last look at The Painting before I go, and leave with that image of Susanna, nubile and naked and disgusted. She’s annoyed, actually, more fed-up than afraid, hands raised to fend off the hideous elders.

in your life?

in your life?