A woman is indicted by a surrealist tribunal assembled in a mansion-cum-brothel, a divorcee dances her way through depression in prohibition-era speakeasies, a man with a crush offers a powerful defense of gossip as a practice of queer mythmaking, a series of scientists are driven to insanity by quantum mechanics: these are just a sliver of the stories unspooled across small press releases in recent years. While mainstream publishing is beset by layoffs and allegations that it is pumping out derivative content designed for BookTok, small presses are thriving by reissuing invigoratingly strange stories that have fallen out of print. Longstanding institutions like New York Review Books, Semiotext(e), and New Directions are flourishing alongside younger upstarts like Hagfish and McNally Editions, while new presses continue to crop up—Doubleday just announced the debut of its own reissue imprint, Outsider Editions.

We seem to be in the midst of a moral panic around how dumb, exactly, we’ve become. Lobotomy memes continue to accrue likes in the hundreds of thousands, while the girls retweeting them, increasingly, have gotten so much Botox and filler that they can’t even forge outraged facial expressions. Boys are locking themselves in cum-stained basements to masturbate on livestreams, which leaves little free time for reading books. The mass embrace of Ozempic is reportedly dampening appetites not just for food, but for anything stimulating at all—Allison Davis recently wrote that writer friends on the drug find that skipping a dose allows them to “come back to life, as do their sentences.” New York magazine recently printed a Stupid Issue mourning American IQs, youth literacy, and the leaching of sex appeal from intellectualism—“being smart isn’t as sexy as it used to be,” apparently. At The Baffler, an array of writers penned “dispatches from a postliterate world” in which literature as a craft is positioned as “well on its way to becoming a lost art.” Last year saw a raft of layoffs in publishing, part of a larger devolution in which the total number of jobs in the industry is down 40 percent from 30 years ago. Meanwhile, there seems to be an epidemic of homogenous, hyperbolic blurbs—if this many books were “blistering,” the ostensibly dwindling community of readers would have third-degree burns by now.

But people have been bemoaning the state of publishing for decades. And readers’ appetite for the out-of-print tomes small presses are bringing back to shelves, their interest in the revelations lurking in the bizarre and the substance harbored by real style, indicates that our brains might not be in quite as dire straits as the op-ed pages insist. Anecdotally, the kids might be alright: My college-age cousin recently regaled me with tales of espionage at her student newspaper so internecine, high-octane, and novelistic I had to assume everyone involved must have read at least some Russian novels in translation, not just their Gemini overviews.

Last month, I met with editors at New York Review Books, McNally Editions, Hagfish, and Modern Library Torchbearers to talk about our dying and decadent industry, what the future holds in 2026, and the enduring romance and detective work inherent to publishing the dead.

McNally Editions, Jeremy M. Davies and Lucy Scholes

McNally Editions was founded in 2022—why found a reissue press then?

Jeremy M. Davies: Sarah McNally [founder and CEO of McNally Jackson Books] was extremely bored over lockdown. She couldn’t be in the stores, a lot of what she would normally do was lying fallow. There weren’t a lot of in-person customer or employee relations. She started getting hung up on all the things she wished were in print but weren’t. It snowballed from there. Every great press starts with a bad idea—that was the one that started us.

The small press landscape is rapidly expanding, and is rife with both longstanding institutions like NYRB and newer upstarts. What role do you see McNally playing in that ecosystem?

Davies: We admit no colleagues or competitors other than NYRB and New Directions.

Lucy Scholes: Reissue publishing is flourishing. Publishing always sees ups and downs for backlist titles, for putting titles into “classic” categories that might in the past not have fit, when publishers were focused on traditionally canonical titles. The field hasn’t always been as open as it is now. It’s a testament to the fact that there are so many things still ripe for rediscovery.

Lucy, you’ve described your role as “more detective than editor.” Can you elaborate? Does the omnipresence of the Internet in both our lives and our discourse add to the allure of IRL sleuthing right now?

Scholes: I suspect it does, to a degree. It’s fun to go around bookshops or libraries rather than use the Internet. Not that I don’t use the Internet, which is very useful for tracking people down. You’re always looking at the back of old books to see what [other] books were advertised, you’re reading reviews to find out what other books are mentioned. That’s quite a fun bit of the work; it can also be frustrating because you go through dry spells.

Davies: People are always staring at me because I look like an absolute philistine standing in a bookstore staring at his phone, but what I am doing is checking: Is this already in print? There’s an awful, sickening moment before you enter the author into a search engine, only to discover that this has already been put out. It’s not the time or place to complain about the Internet—it makes what we do possible. Whereas walking into a library sale in a small town is not absolute chance, but you don’t know what you’re going to find. Ex-Wife, which is one of our most popular books, was pure chance. I saw it in a library sale, picked it up, and it’s great. That day, my instincts were functioning.

Speaking of physical sales, how does having a store associated with your press influence your process?

Davies: If a press has a never-before-translated Lithuanian Dadaist novel from 1931, I’m the guy who will buy that. So it’s good to be able to talk to a bookseller who will say, actually, Jeremy, pull the brakes.

Scholes: At the other end of the process, they’re incredibly good at hand-selling our books. It’s booksellers who are ultimately getting texts into the hands of readers.

What has been your most surprising hit? Has anything you expected to find an audience failed to pan out?

Davies: The response to Ex-Wife was exactly what we hoped for. People thought it read like a contemporary book. We’re enthusiasts, that’s the great thing about publishing. Even commercial publishing is an engine that runs on enthusiasm, and it can be misplaced enthusiasm. We’ve been enthusiastic about books that have come out, and we’ve realized the time wasn’t right.

Your list includes famous names alongside ones readers have likely never heard of. Is there an active effort to balance big names with ones you believe should be more recognizable?

Davies: Every reissue press, ourselves very much included, has great books that we would love to get our clammy hands on, if only the writer were slightly less famous. On one hand, we’d love to do a season full of huge names. But that would be less fun, because the discovery is part of it. Part of the pleasure is: people look at our list and go, I have no idea who this is. Why is it next to E.B. White?

Jeremy, you’ve said that the dead write better than the living—a take I was raised on—but I’m curious why you think that is. What is missing from the contemporary literary landscape?

Davies: That will go on my tombstone. I’m happiest reading dead people, people who aren’t actively attempting to write into this moment, who have no concern about the market. That is the reason there are so many reissue presses now, because there’s a real desire for escapism. I’m not talking about escapism in the sense of wanting to see a superhero movie instead of the next Paul Schraeder film. I’m talking about escapism in a very literal sense: I want to get away from this moment, because this moment makes me feel bad. The media of this moment feels flat, unpleasant, and oppressive. I’m not saying that a Victorian novel is superior to the 21st century novel, but I would say they provide different vitamins. They definitely can’t just be a blog entry or a path through Wikipedia, to choose two versions of the contemporary novel that don’t particularly interest me.

It’s extremely difficult to write about this moment without it being mealy, bland Internet writing, or a very fragmentary, unsatisfying experience. It may be that we’re not built for satisfactory aesthetic experiences right now. That’s another reason that we need to see what has been done. Meanwhile, I’m the one who’s always arguing for the deeply unpleasant fragmentary novels to go on the McNally list, so I should say I’m a huge hypocrite, but I definitely feel the malaise.

I find that people with the best taste are often huge hypocrites, so keep it up.

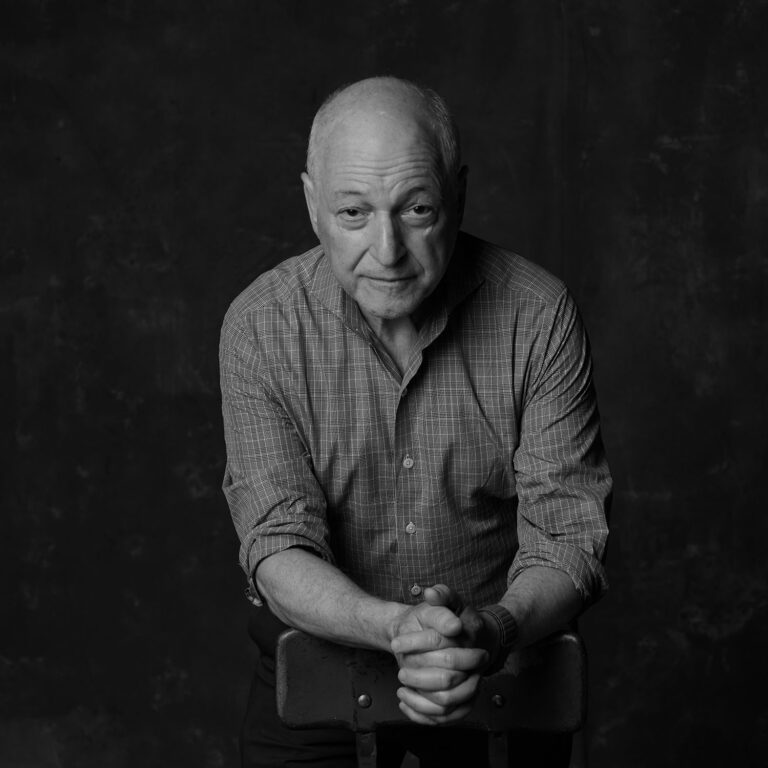

New York Review Books, Edwin Frank

You founded NYRB Classics in 1999, so you’re the elder statesman in the scheme of presses I’m speaking to. What was missing from the literary landscape back then, and why did you decide to embark on this project?

Edwin Frank: In 1996, I was working for a company called the Reader’s Catalog, which was basically a giant Sears catalog offering the 40,000 best books in print. Jason Epstein thought a catalog would help to make up for the disappearance of independent bookstores across the country. I discovered a number of books I thought were good books that were not there, and began to make a list, and said, Why are these books out of print? So it was a gamble, and though we were not aware of this, a contributing factor to what would be our success was that the big publishing houses were all becoming corporations, publicly traded properties with the things that go along with that: stocks, making sure shareholders are happy, showing growth each year. It meant that they turned away and began to neglect the backlist.

You’ve said that back then you were collecting “low-hanging fruit,” as in there were so many great books out of print, and so few presses doing reprints. That is no longer the case. Why do you think we’ve seen a boom in reissues recently?

Frank: It’s analogous to the way people began to collect vinyl. There became a historical dimension to people’s awareness and their cultural commitment. It all started up in the wake of the pandemic, because backlist sold very well in the pandemic. Another factor was the interest that came with MeToo in reasons why certain writers are neglected, and a programmatic effort to rediscover women writers.

How do genres, which can be quite deterministic in mainstream publishing, function in reissues? To me, they seem more like witty epigraphs than strict definitions in your books.

Frank: Going back to the record analogy, people who are serious about music might have an ear for reggae and also be willing to listen to Stockhausen’s electronic music. If genres were a creation of the 20th century, by the end of the 20th century, the ways in which they seemed to delimit certain kinds of interest seemed to be collapsing. For serious writers, a serious book might be a book where you mixed up your genres.

What have you published recently that surprised you in how it performed, in the responses elicited from readers?

Frank: Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico. I thought the odds were rather low that that would be successful. It’s a book where you sit, for much of it, wondering, Is the book guilty of being as superficial as the people that it is sending up? It speaks to a generation, about a generation. Nastassja Martin’s book In The Eye of the Wild: She’s an anthropologist doing work in Siberia, and she was attacked by a Kamchatka bear. The people she was working with saw people who had endured a cross-species encounter as ontologically transformed. Her book is a horror story of bad treatment in a Russian hospital, even worse treatment in a French one, and returning, in a non-Elizabeth Gilbert way, to work through her trauma.

Those are 21st-century books, but you’ve written that 20th-century novelists “existed in a world where the dynamic balance between self and society that the 19th-century novel sought to maintain can no longer be maintained, even as a fiction.” Does the 21st-century novelist face the same problem, amplified by networked communications?

Frank: What seems to be at the core of what’s going on now is a sense that notions of the self and society have both imploded or exploded in ways that make maintaining balance very difficult. It is a maelstrom, where outside information is seeping inside all the time, and is that information provided by an organized society? It can be, but we know, increasingly, it could also be totally delusional or manipulative. A book like Gravity’s Rainbow, with its massive clouds of paranoid fantasy and sense that reality is as much a movie as anything else, seems to be looking to where we are.

Introductions are a genre unto itself—often containing elements of memoir, journalism, biography, and criticism. How do you pair authors with texts?

Frank: I want somebody who will take the time to read a book attentively, appreciatively, which doesn’t mean it has to be completely approvingly. I don’t want a hyperbolic blurb. For the reader, I don’t want you to feel like you are following a tour guide around a museum, but more like if you were to go to a museum with a painter, and the painter looks at the picture and says, This is what really strikes me.

What are we seeing too much of in contemporary publishing?

Frank: Frankly, I find the fascination with issues of identity almost baffling. It comes from all over the place, and I find it strange to think about it as so fixed. I find the use of a verb like ‘to identify’ strange—when I was young the only people who identified things were the FBI. When I see submissions, there are also a huge number in which climate change is somehow juxtaposed with somebody discovering some ancient, esoteric way of thinking from the early modern period, which relates to an apocalyptic something-or-other.

Hagfish, Naomi Huffman and Julia Ringo

You two run the youngest press I’m speaking to. Can you tell me why you decided to start Hagfish when you did?

Naomi Huffman: That is great to hear—I haven’t been the youngest anything in a long time [Laughs]. Julia and I met when we started working at Farrar, Strauss & Giroux. I was working in Katherine Dunn’s archive, which was my first archival publishing experience. The manuscripts included Toad, a novel Dunn tried to get published in the ’70s that came out in 2022 from FSG, and a collection of short fiction, Near Flesh. I hadn’t known she wrote short fiction and was really excited—and appalled—that it was just sitting in her archive. No one was advocating for it. That project was the genesis. It’s exciting to have a mission in publishing, where so many aspects are thankless. Julia joined me to start Hagfish in earnest in 2022.

Julia Ringo: We started as an editorial studio. Within a year, we’d signed our first book, [Iphgenia Baal’s] Man Hating Psycho, which just came out in November. We always had an interest in working with estates, mining the archives for books that have fallen out of print. It was a different sort of project, but we read it and knew it was a Hagfish book. We wanted our first book to be a reissue, so we didn’t launch until this year with Rosalyn Drexler’s book To Smithereens.

Hagfish books bring complex feminisms to the table, feminisms that can laugh at themselves and are willing to get bruised. Do you see connections, or a kind of conversation, happening between your contemporary and reissue writers?

Huffman: We thought we’d release a reissued book and a book we saw as its literary descendant annually. Instead, we decided to keep things loose and allow ourselves freedom, but there is still that implied connection. The overall project of Hagfish is drawing this line between someone like Drexler and, for instance, Baal: There’s something about the feminism that Drexler was writing towards that made it possible for a book like Man Hating Psycho to exist. We’re interested in legacy, what’s unspoken or un-celebrated but gets passed down anyway.

That notion of diagonal descendants, these books as cousins instead of a nuclear family, feels related to me to your choice to reissue the work of still-living writers, rather than go the traditional reissue route of publishing dead people.

Ringo: We imagined working with more estates. So far, we’ve been in conversation with living writers exclusively, which is really rewarding. Rosalyn was aware of the rave in the Times. It was really meaningful to participate in the launch of Fish Tales by Nettie Jones: Watching her walk into the packed bookstore was its own reward. It was wonderful to see her face as she looked across the room and saw so many people she loved, but also strangers.

Where do you look for writers, and what are you looking for in the work?

Huffman: Sometimes we read about a woman in the biography or obituary of another woman. We’re looking for a frank sense of humor and a working class perspective. Feminism that isn’t afraid to laugh at itself. That feels like part of the opportunity we identified: there was space for an emphasis on feminist publishing that would embrace younger audiences and appeal to their sensibilities. These aren’t books we’re fighting for simply because they contribute to the feminist canon, but because they’re really, really good.

That feels aligned with your choice of name—embracing a reptilian, winkingly repulsive femininity. The canon you’re building willfully refuses the easy, trendy but often reductive framework around “rediscovered, forgotten” women.

Ringo: We try to push back on this idea that these women were just languishing in some hole, so we are saviors “rescuing” them into the same environment that didn’t celebrate them in the first place. The remedy is being conscious of the conditions in which this work was created. We’re interested in writers who are working other jobs, who are mothers, who had many other demands on their time, and the reasons why their work slipped through the cracks. Another unsought benefit of working with living writers is that we can ask them to write an afterword. It’s a chance for the writer to give the work context, which feels like giving them agency back.

Huffman: It would be insulting if we published these books mournfully. Instead, we think, Isn’t it such a compliment that this is still resonant today?

Speaking of contemporary resonance—why do you think we are seeing so many new reissue presses now?

Huffman: There’s a trend emerging—there’s a romance about searching for this work, finding it, repackaging it, and redistributing it that is appealing to thoughtful readers from all walks of life.

Ringo: There was a time—pretty recently—when a reissue would never be treated the same as a big debut from a young writer. That’s still the case, to an extent—the same amount of resources are not pouring into this area as they are into more traditional avenues. We offer an exciting deviation from the norms of publishing, in that it doesn’t feel attached to the machine.

The Modern Library Torchbearers, Clio Seraphim

Torchbearers began in 2019. Can you talk about its evolution since?

Clio Seraphim: Torchbearers was started by our publishing director at Modern Library, which focuses on the general canon. It was time to expand the notion of what the canon means. There are all these great female writers who never got their due, who we can now spotlight.

You also edit contemporary writers. How does your work with dead writers influence your editorial work with living ones?

Seraphim: They fit together in a holistic way. I’ve always been interested in writers who are doing something unusual with form, character, style, or setting while retaining a grounding in real human experience. [Elaine] Kraf published last in 1979, but kept writing until her death. She kept all her rejection letters, and would write rebuttals: I know you are rejecting me because I’m a woman and I don’t fit into this male publishing establishment. That, at least, has changed—there is a wider tent for diverse voices. Seeing authors who were doing experimental things ahead of their time makes me excited. The success of books like Big Swiss or My Year of Rest and Relaxation or the BookTok trope of “weird-girl fiction”—people are thinking outside the box.

Has anything really surprised you, in terms of reader response, since you started doing this work?

Seraphim: The amount of authors who come out of the woodwork to say, I am a massive fan of that author, or, I discovered these books years ago and didn’t realize someone was republishing them. Lauren Oyler is one such writer, who’s doing the introduction for Memory House, the previously unpublished Kraf novel we’re releasing next spring. In publishing, we talk about the pass-along quality of a book, and it is fun when you see that bearing fruit.

Why do you think we are seeing such a spike in presses putting out reissues now?

Seraphim: We’re in a very chaotic world, so you want to recapture some nostalgia or look to the past for lessons. Something I learned from our Torchbearers books is: issues I feel connected to as a woman are issues that women have been dealing with for a very long time. There is a sense of solidarity and community with these writers, while they also allow you to access the reasonable depression around the fact that so many of these issues remain.

Are you noticing any trends in what gets reissued lately?

Seraphim: The books we reissue are books that found their cult audience decades ago, and are still interesting today: There’s always going to be an audience for the freaky.

in your life?

in your life?