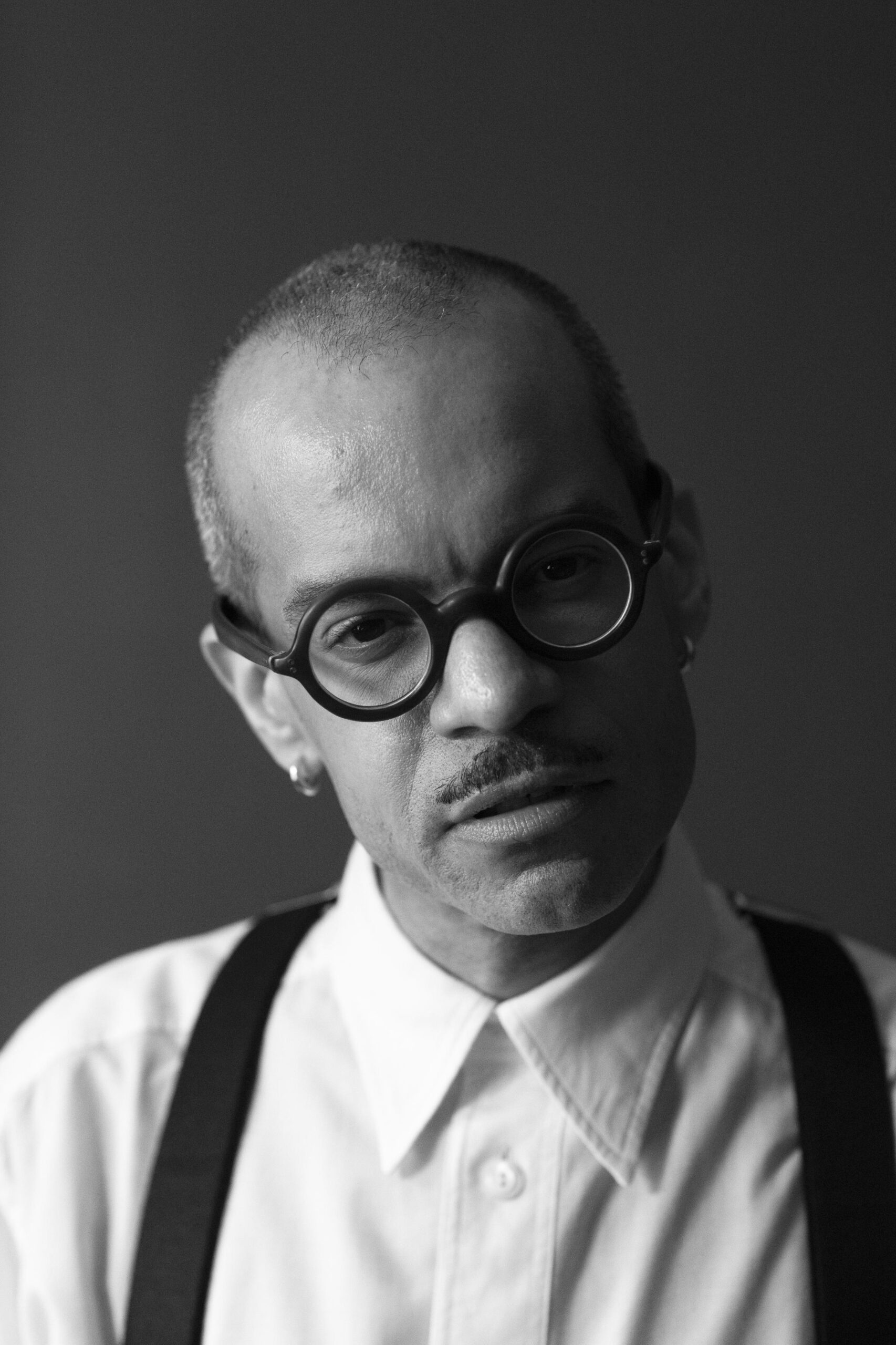

“I don’t understand how people can be so casual about theater,” says Carlos Soto. His eyes tear up as we speak, emotion thrumming through his limber frame. Today, he’s draped in a handwoven kimono; other days, it’s Margiela-era Hermès or early Lemaire (“It was more romantic then,” he says). We lean toward each other over our table, surrounded by rowdy West Villagers at the vaguely Shaker Commerce Inn. “Theater is the closest I’ll ever come to a religious experience,” Soto says.

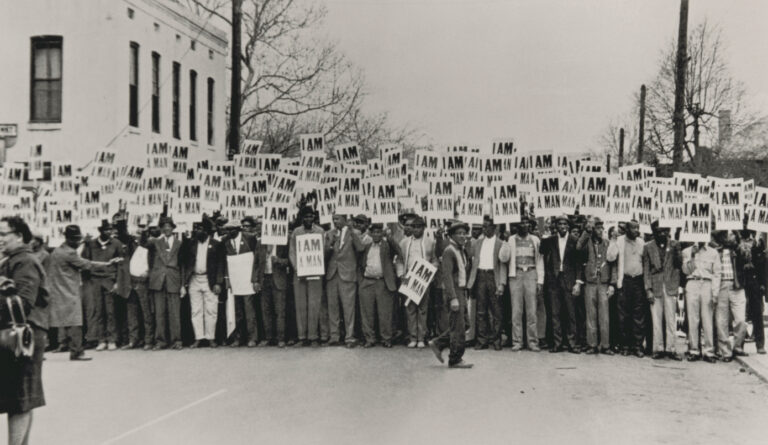

He is an extreme person—”blunt,” as he puts it—whose essentialist approach to set and costume design has resulted in some of the most refined and emotive visual expressions on the contemporary stage, having crossed from opera to pop to comedy, creative directing and designing with the likes of Solange, Shikeith, David Lang, and the late Robert Wilson. “He can be uncompromising in his belief and his designs,” Wilson said before his passing in July of this year. “He is not afraid to do the wrong thing.” The “wrong thing” is always unexpected, and Soto’s comfort in that territory has refreshed centuries-old narratives in desperate need of reinterpretation.

When we meet, Soto has just returned from Zurich, where he wrapped a production of Robin Hood at the Schauspielhaus directed by artist Wu Tsang, and is spent. In Soto’s Sherwood Forest, righteous thieves fuse with the woodland creatures around them: Robin Hood is a fox, squirrels make up his choir, and Little John is a grizzly bear. His costumes were inspired by animal memes and extensive research into Japanese Noh theater masks, which depict the stages of transformation from human to beast, triggered by intense emotions like rage or jealousy.

Drawing connections between ancient Japanese theater traditions, parasocial meme circles, and a British 14th-century legend demands a singular talent. Soto’s wildly inventive approach springs from a lifetime of venturing down rabbit holes. “He is extremely sophisticated, highly educated and intelligent, well read, and creative,” Wilson told me admiringly. Born in Harlem, Soto spent the earliest years of his life in his parents’ native Puerto Rico. When the family returned to New York, they lived in the Bronx, where Soto still resides. In his adolescence, he began consuming films by Derek Jarman, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Federico Fellini, while spending hours in his prep school’s drama club. “Performing is a strange form of therapy for a painfully anxious person like myself,” says Soto.

At 15, he met Wilson. By 17, he was the youngest person among the group of artists that the legendary theater director and playwright invited into his laboratory for performance in Water Mill, New York. At 18, Soto apprenticed under the costume designer Frida Parmeggiani on Wilson’s production of Lohengrin at the Met, before enrolling briefly at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. It took less than a semester (and an offer to work with Umberto Eco and Ryuichi Sakamoto) to recognize he would learn more outside the confines of academia than within them. He dropped out.

More than 20 years later, Soto’s sets, costumes, and creative direction boast a perplexing mixture of ease and precision while confronting a richly varied array of material. He has outfitted Terence Koh for his monthlong performance at Mary Boone Gallery in 2011, designed costumes for Marina Abramović, worked with Philip Glass, and even led production design for comedian Jenny Slate’s 2024 run at BAM. He deftly handled Robert Mapplethorpe’s flagrant fetishism in a presentation supporting an oratorio by Bryce Dessner of the National in 2019.

Solange’s triumphant When I Get Home album from the same year is indebted to Soto’s costume design and direction. “In Carlos’s portfolio of works, you see a style, a language, a voice that is so uniquely him at the highest level of taste, but also so vastly different from project to project,” says Solange. “Carlos is an enormous part of my process in prompting me to consider things like the cues in a performance, how instruments enter and exit the stage, how we implement transitions… These might sound like small details, but his ability to charge energy in even the quiet moments is light-years ahead of anyone I have worked with.”

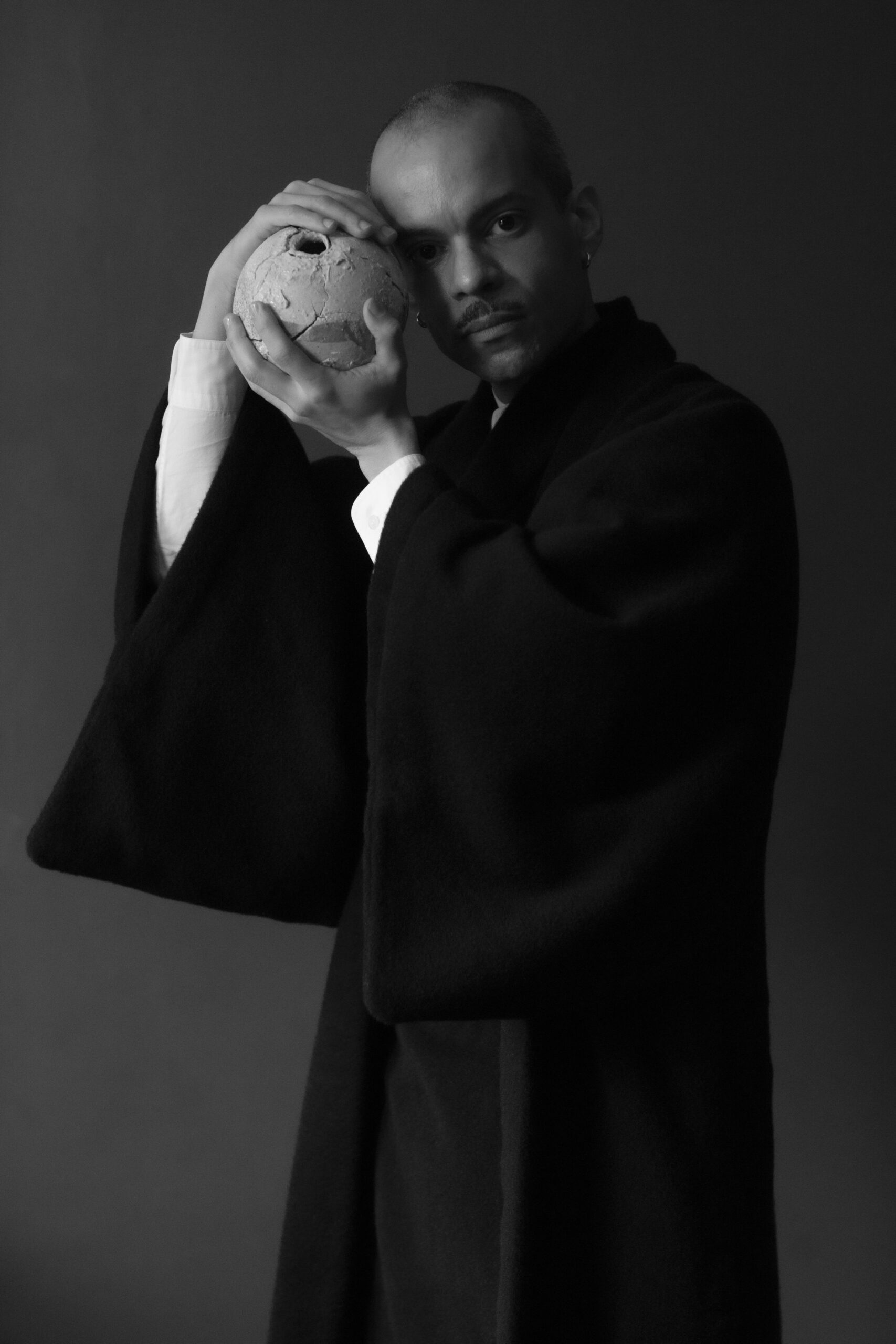

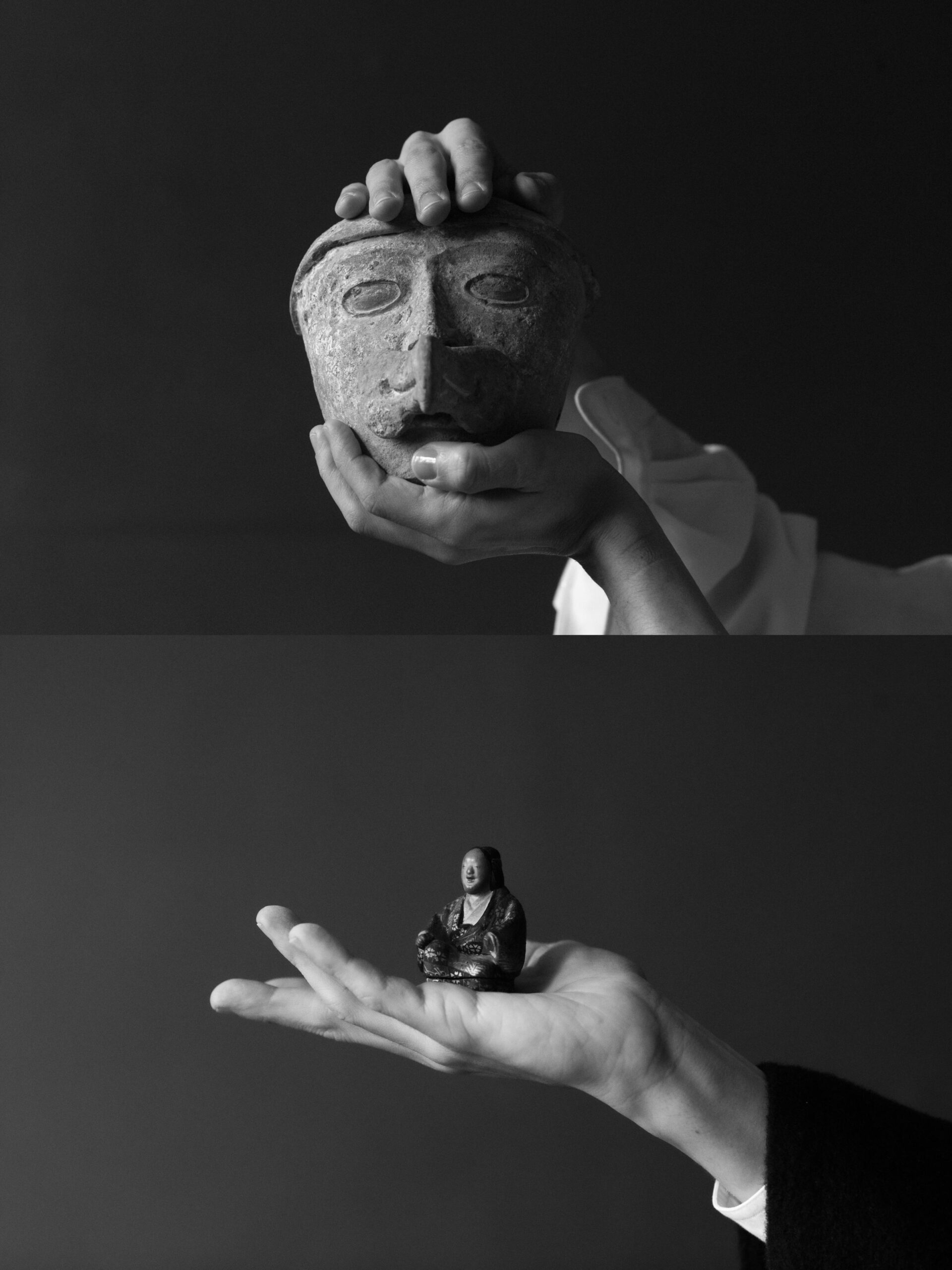

It’s not that he is a theater person per se. It’s more that, like most polymaths, he had to choose a lane. “I chose theater because it was the only means for me to make the installations I wanted to make,” Soto says. His two-bedroom apartment in the Bronx, a repository for artifacts as priceless and idiosyncratic as the artist himself, offers another avenue for world-building. Soto arranges his objects, which run the gamut in terms of era and medium, in a way that shocks his eye into attention. None of his objects is coddled for its fragility or covetousness: Soto eats off Shigaraki and Iga ware plates. He uses pottery in winter and glassware in summer. He serves his tea in all manner of rare vessels, usually Japanese, and often dependent on the type of tea leaf.

“My home is an experiment in curation,” Soto says. “I move things around, even if just to put them back where they were; creating new tensions between things, new connections, even if they’ve lived in the same room for years.” This ritualistic process of trial and error carves out new avenues between objects as disparate as Bauhaus furniture, Dutch cactus pots, thousand-year-old Ecuadorian figures, and vibrant Amazonian featherwork. An unexpected thread could be drawn, for example, between his Shaker candlestand and Taíno pestle—their simple lines and surfaces warm and inviting.

An industrial lamp by Tommaso Cimini juts into space like a visitor from the future, while the beautiful stone head of an Aztec youth is perched nearby. A Sudanese ivory bangle carries a similar hue to a white patchwork Joseon pajagi cloth: one valued for its milky purity and implied violence, one for its signs of perpetual repair. Both have felt the touch of countless hands. “I either want an object to tell me a story or to disappear,” Soto says with characteristic directness. “My objects act as aide-memoires. They remind me to live.”

Such a reminder might seem unnecessary, but living, for Soto, is a more demanding endeavor than one might think. His days are structured by creation in its most unfettered form: referencing rare texts collected over decades; peering quietly out the window as a wisp of an idea takes shape; and putting pen to paper, turning those wisps into one clean, powerful gesture. His work is like a well-aimed punch: boiling narratives down to their most essential ingredients and striking the truth with fiction. In this state of constant invention, Soto triumphs where so many have failed, collecting the references of the past like moss and transforming them into the new.

Order your copy of CULTURED at Home for more stories like this one here.

in your life?

in your life?