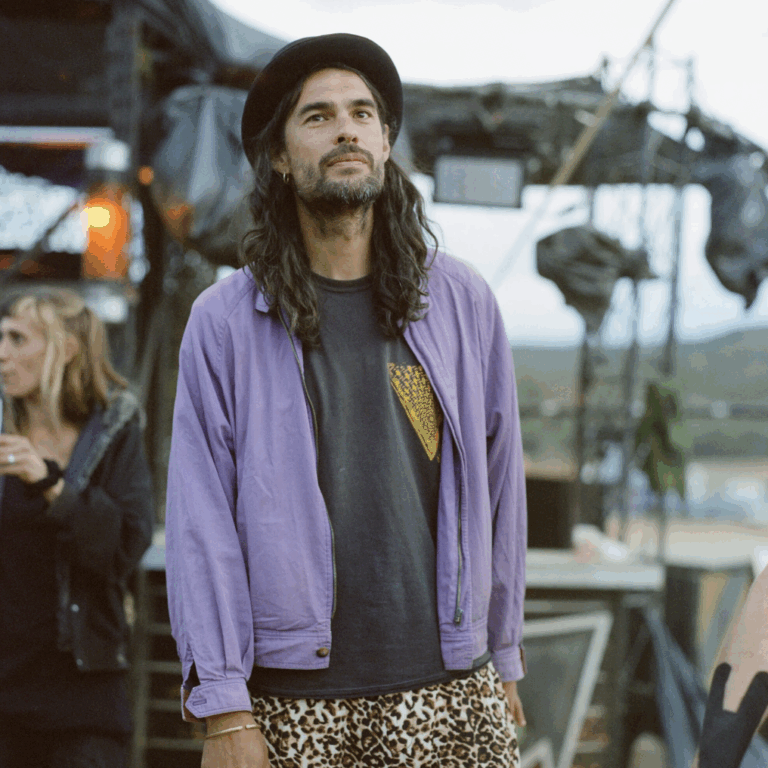

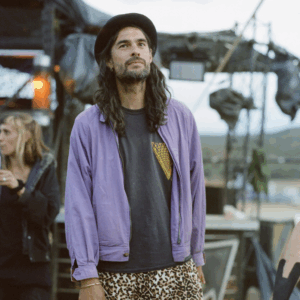

Treat Me Like Your Mother sets its stage not with spectacle, but with a plea for gentleness and care. Drawn from an Arabic expression asking for mercy, the title reframes motherhood as an ethical position—in this case, one rooted in responsibility for the trans community in Lebanon. In his new documentary, Lebanese photographer, filmmaker, and Cold Cuts magazine creative director Mohamad Abdouni documents the lives of trans women refusing the narratives most often imposed on them. Instead of extracting trauma (although its surfacing is more than welcome), he makes space for how these figures to choose how to tell their own histories in forms that are personal, nonlinear, and surprising.

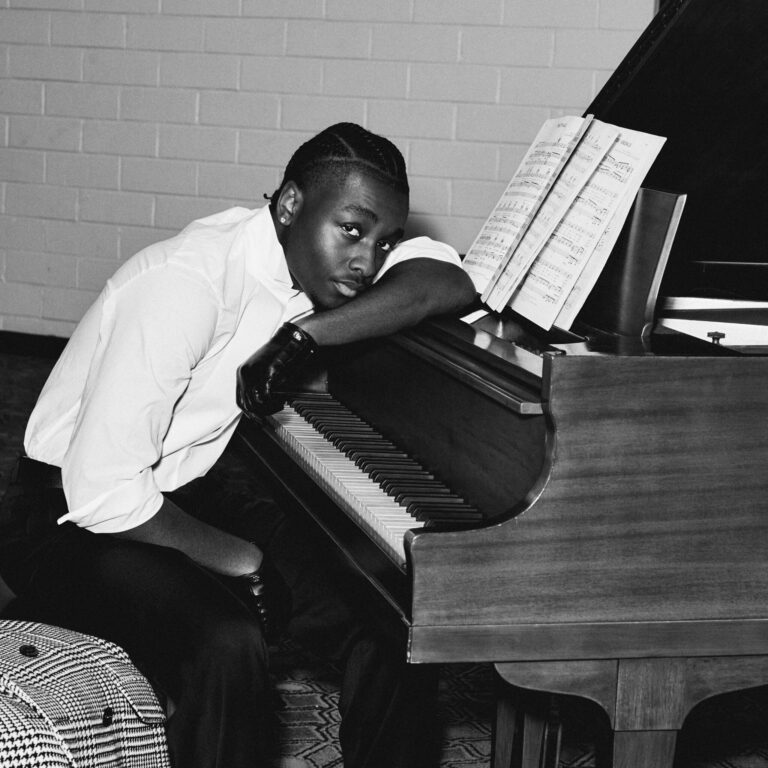

As photographer and conversation partner Michael Bailey-Gates observes, “there’s always pressure to lean into traumatic angles that the media wants, but your work resists that.” Instead, the film is a testament to celebration as resistance and the urgency of learning queer history from those who lived it. For CULTURED, Bailey-Gates and Abdouni enter into dialogue about the grace of letting trans women define the terms of their own visibility for new audiences.

Michael Bailey-Gates: To start, can you walk us through the interviews? They’re so beautiful and intimate—you see a special tenderness in them.

Mohamad Abdouni: I think this tenderness comes with the artists. That’s the only way to do such work, as it’s very intimate. All of the women were very skeptical at first, because they are used to being approached by journalists rather than artists. We would always start off by asking how they would like to tell their story, and get these pre-rehearsed answers, starting with “the first time I was raped was…” and we would react like, “hold on, this is not what we want. It’s okay if this is something you want to talk about, but this is not what we’re looking for. We are queer, gay, lesbian, trans people that are young and that are looking to you for history because we don’t have our own recorded.” Eventually, each of the women would let her guard down, realizing that there is a genuine and gentle intention behind what we were doing.

Bailey-Gates: I was looking through Cold Cuts, because I really wanted to get my hands on an issue before we talked. Is it somehow connected to the documentary?

Abdouni: The documentary was never planned. At first it was a book, accompanied with transcriptions of oral histories for these wonderful 10 women that we spoke to. A film was a much later thought, evolving from the archives. Where the book de-centers me completely—I’m there as a tool to record these women’s stories—the film does the opposite somehow, centering me back. This documentary is a reflection of why I wanted to do this project, why I felt so much comfort with these women, and what these women represented to me growing up.

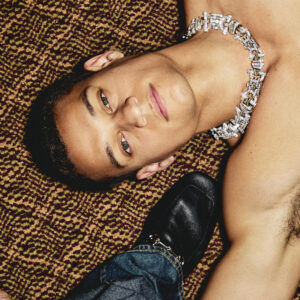

Bailey-Gates: I feel like we’re remaking photography on our own terms. There’s always pressure to lean into traumatic angles that the media wants, but your work resists that. Instead, your stories are colorful, personal, and resonate far beyond a strictly queer lens. I see it almost as looking over the garden wall: it’s deeply personal, but reaches beyond the self. In my own practice, when I focus on the hyper-intimate aspects of my life, they reflect a broader truth people connect to. How do you balance keeping the work personal, while still making it accessible?

“Your stories are colorful, personal, and resonate far beyond a strictly queer lens. I see it almost as looking over the garden wall: it’s deeply personal, but reaches beyond the self.”—Michael Bailey-Gates

Abdouni: I also find a lot of that in your work, and I think the big umbrella word is celebratory. Just celebrating those people, these details, the things that we love. Celebratory is what takes that personal or intimate [moment] and makes it universal. As soon as you’re celebrating something, the attention shifts from trauma to a celebration.

Bailey-Gates: In my own work, I’ve been interested in joy as a form of revolt, and I see echoes of that in yours, especially in how you use home footage and these hyper-personal moments from your childhood. Looking at Cold Cuts and the new documentary, it feels like you mirror that approach when you speak with these women, and by including their childhood photos in the archive. I wonder: how did you approach the histories of the women? Was it the same for every person or did each one lead the way?

Abdouni: They absolutely led the way. What I found fascinating was how every single woman views their life in completely different ways. For example, one of the women, Antonella, sections her life into pre-surgery, surgery, and post-surgery, those being the three main arcs of her life. Someone like Katia—who I would relate to much more in terms of telling my own history—chapters her life through boyfriends and relationships. Someone like Emma Abed just has a midpoint—the accident—that splits her life story in two: pre-accident and post-accident.

Bailey-Gates: Your work resists being categorized, like how we were talking about the evolution of the documentary that wasn’t meant to be a documentary. Where would you categorize this project in 2025?

Abdouni: I think the fact that I don’t go in thinking where the work would be categorized allows me to do the work as freely as I do. Even the film itself is difficult to categorize, in a sense that it has elements of a documentary, but also it’s just a very personal essay.

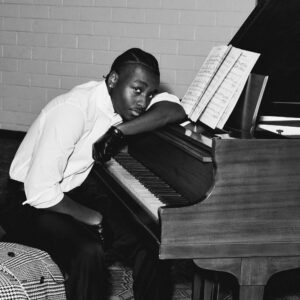

Bailey-Gates: Thinking about my own work, the lines get so blurred. Any time I have, regardless of budget, health, or where I am geographically, becomes time to make work. Fashion, a photo essay, or something intimate with a friend all fall under the same umbrella of my fine art. There’s a theme in your work I love: the pictures of you and this girl—maybe your best friend? I’ve seen a handful of them, you two lying on a couch in the morning light. She has long black hair. They’re so beautiful and timeless that I kept wondering who she is.

Abdouni: That is my oldest friend [Clara]—we’ve been friends for more than two decades now. Geographically, we haven’t gotten to spend a lot of time together over the years, and this is our way of documenting a life that could have been. It’s very beautifully strange to me that those are the photos that struck a chord for you. I don’t think I’ve even shared that many of them.

Bailey-Gates: It’s the way you’re looking at each other in the images—there’s a lot of eye contact and a more editorial look, like when I’m photographing somebody. There were a few images where you were always looking at each other, and I found that so memorable.

Abdouni: She’s a photographer, and most of these images are probably taken by her, or she could have been the one to set the frame and the timer. She also does very different work from you and me. Whenever my imposter syndrome kicks in, it’s because I feel like she’s the true definition of an artist in the traditional sense of the term, in the sense of how they breathe their work.

Bailey-Gates: I’m curious—did the intimacy you’ve learned through photographing your best friend carry into your work with the documentary subjects?

Abdouni: Maybe unintentionally. However, the photos with Clara aren’t something we would think of in an institutional context—they belong to the realm of a personal photo album.

Bailey-Gates: That makes sense. I’ve been thinking about how we learn to make an intimate image, and how those details, like the 1990s backdrops you sourced, carry personal history into new work. I’m always wondering how the patterns from my own life shape what I do, whether it’s with a friend or in an editorial setting. How do you pull those threads into a documentary?

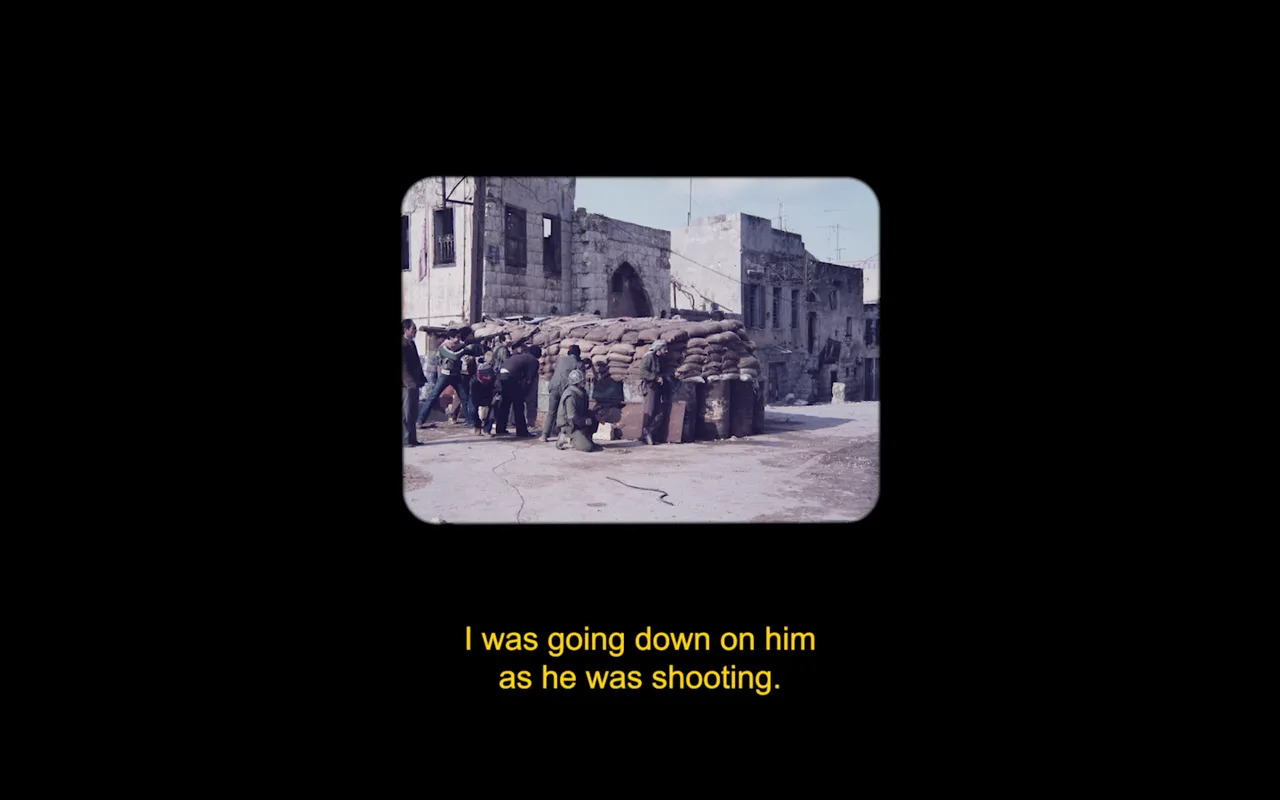

Abdouni: I love these questions because I don’t have immediate answers to them! What comes to mind first are the old studio backdrops from the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some elements feel universal, but others are deeply specific to Beirut. The studio portraits from my childhood were always cold to me: there was no intimacy, no connection to the photographer. It was quick, uncomfortable, and somehow endless. So I took that same setting with the women and inverted it, using something that was sterile in my memory and turning it into something intimate.

The film’s title, Treat Me Like Your Mother, captures that reversal in a way.

Bailey-Gates: Since the film is so personal, tell me your tricks. How do you approach that level of intimacy? And where does the title of the film come from?

Abdouni: The title has layers. “Treat me like your mother” is a loose translation of an Arabic expression that came up in the women’s stories—a plea for mercy, for gentleness. If you come for me, just treat me as if I am your mother. We ended up going with this title because of how much motherhood was present throughout all of our conversations. Whether it’s Antonella, who was a mother in an orphanage for years, or Mama Jad, whose one single wish in this life is to be able to feel the pain a mother feels delivering and giving birth.

in your life?

in your life?