Working 65 years apart, directors Jean-Luc Godard and Richard Linklater share a conviction: cinema moves forward when rules are treated as suggestion. After leaping from criticism to creation, Godard moved at a breakneck clip. Twenty-three days of shooting. No permits. No schedule. Just a girl and a gun. He was now a director—an auteur—and nothing could stop the film that followed, Breathless, or the tidal wave of the French New Wave it came to symbolize.

Linklater’s latest film, Nouvelle Vague, tracks Godard’s frenzied sprint toward cinema’s hall of fame. Early on in the movie, actor Guillaume Marbeck’s Godard insists that “the best way to criticize a film is to make one.” It’s both manifesto and dare from the school of the late director. Linklater advances this point as the narrative progresses—and Zoey Deutch is there to help him.

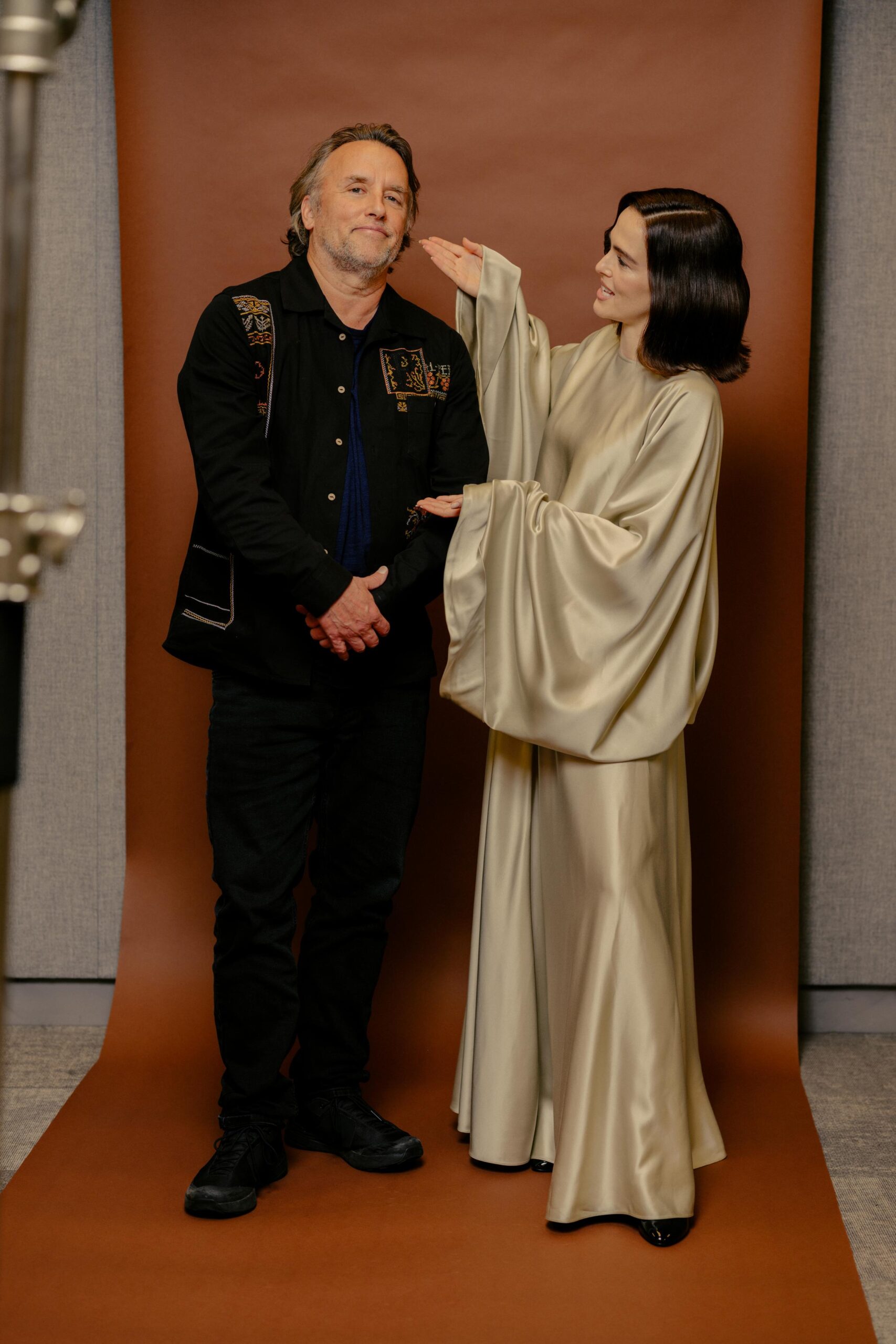

Deutch inhabits the gamine charm of Breathless love interest and French New Wave icon Jean Seberg: blond pixie cut, striped shirts, playful French, long cafe lunches. Her performance has helped Nouvelle Vague earn a Golden Globe nomination. For CULTURED, she led a conversation with Linklater on the serendipity of Hollywood, and the pressure of playing an icon you’ve never met.

Deutch: It’s been almost 10 years since we worked together on Everybody Wants Some!! How does it feel to reunite, and how has your creative shorthand evolved since our last project?

Linklater: It was just so damn different, and it was beautiful that way. It only helps to have worked together before, because you know each other’s rhythms and there’s already a trust there—it’s wonderful. One of my joys is reconnecting with people I want to work with. If I have any pain in this world, it’s when the planets don’t align and I can’t work with the same actors again. I called this a long time ago, Zoey. I told you, “Hey, I’m going to do this thing and you look like Jean Seberg—I think you can do it.”

Deutch: It was such a privilege to work with you at 19, and then when I was 29. Your methodology—the way you like to work and your systems you have in place—didn’t feel any different, but I do. I felt really grateful to get another chance to learn from you, and be a little bit more present than I was when I was a teenager. Oftentimes in life, you look back at opportunities and go, “Damn. I wish I had another shot at that” or “I wish I could have enjoyed it.” It was really cool to have the chance to identify the things that have changed in me.

What aspects of the language or energy of Breathless still feel ahead of their time to you?

Linklater: That film is technically old in cinematic years. What was so fresh and new in 1960 is half as old as cinema now, but that film retains a little punk-rock ethos. It’s so irreverent and does things so differently. It’s still a little startling in a way. When [Jean-Paul] Belmondo [who plays Michel Poiccard in Breathless] looks at the camera and tells everyone to go fuck themselves if they don’t love the country, you don’t see that a lot to this day.

I’m always mesmerized by Belmondo and Seberg. They’re the key there, but frankly, I forget what they look like. For me, you and Aubry [Dullin] are them. I’m still in a nice bubble we created that you are them. I prefer our characters.

Deutch: It’s obvious that you and Godard are very different filmmakers. If anyone ever speaks disparagingly, you oftentimes jump in and defend his honor, his artistry, and his character.

Linklater: The truth is, Godard’s so different from everybody. I think I’m in the more normal spectrum of how you make movies, whereas I think that most directors have a reputation for being difficult. In the case of Godard, I think he’s just dealing with his own neurodivergence. He’s kind of a critic by nature, and I think he wasn’t attuned to other people’s feelings so well—wherever that landed him on this spectrum of ours. I think he was doing things inadvertently that did hurt people’s feelings. He did have long-term friendships and he was not a dark-hearted guy. He was just a heady guy who saw his point to be critical of everything.

Deutch: What drew you back to Breathless specifically? Why did it feel like the right moment to revisit Godard’s original set?

Linklater: This one’s been brewing for a while. I never considered Breathless even my favorite Godard film. It’s his most unusual film. It’s his first film, but I think he was a little aloof from Breathless the rest of his life. He took a lot of that methodology forward.

Deutch: It’s funny, I asked you the other day, “How many projects do you have right now that you’re working on?” It was quite a few. With a lot of other movies you’ve made in the last decade, it feels like there’s a spiritual kind of cool, collective unconscious thing that happens when they’re supposed to. I have loved that as a positive, not a negative, to this craft: that you work on all these things, and if it doesn’t happen, that’s not a death to the piece, that’s just not the right moment for it.

Linklater: Almost every film I’ve made has had some gestation. I sent Nouvelle Vague out years ago to a few producers and a guy who was the head of a company. I just thought, I’m ready to make this. It’s really satisfying to get something made that you did work on for that long.

Deutch: Can you talk about the experience on set for Nouvelle Vague?

Linklater: It was so different for me, but in the best way. Zoey and I were the only Americans nearby. We had a French crew so it put us in a little bit of a bubble, but I loved that bubble. When you’re the director of a movie, you’re in on the buzz of every problem. This time, it feels like I was left out so much. If someone told me in English what was going on, then I could help them. It seemed like such a visual art project for me—it was just the world of 1959 that we were creating. Pure joy. How did you feel, Zoey? It was a little chaotic, on the surface.

Deutch: Well, I’m used to chaos as a prerequisite. One of the things I remember is how intimate and small it was. For context, we got ready in whichever rooms were available nearby. It was extremely cold and raining almost every day while we were shooting.

Linklater: We shot it in August—it’s supposed to have a summer feel—but we were wearing coats.

Deutch: It felt to me like the fantasy version of being an actress. At the same time, it was really scary, because I was constantly in my head about the French and her physicality. Seberg was so much more graceful than me, and she moved her body in such a different way, that, in a great way, I felt the least free I’ve ever felt performing. I couldn’t improvise or add little bits and bobs. Though I was the least free I’ve ever been, I felt like I had some of the most fun I’ve ever had.

Linklater: It was all, “What would Jean do?” You are playing Jean Seberg. She wasn’t that good at French—if she mispronounced a word in French, well, you had to do that. We were in a Jean Seberg box, but it was a pretty good box to be in.

Deutch: I love her so much. The pressure of playing a real person became so much more clear when I was in that world.

Linklater: I felt that too, for all of these people.

Deutch: That was a really big transition and realization for me: “If she got to see this, would she feel like I saw her?”

Linklater: From the first time you opened your mouth as Jean Seberg, I knew she was smiling somewhere. No one in this movie is still on planet Earth, yet they were all back together again. As fraught as Jean’s life was at this moment, as traumatized as she had been professionally, here, she’s Jean Seberg. She’s in France, she’s young, and it’s all still ahead of her.

in your life?

in your life?