It seems wrong to sugarcoat the year and unnecessary to belabor the bad news, from the tectonic upheavals and wanton destruction to the chef’s kiss insults from on high (i.e. Truth Social posts). But looking back through my photos and notes, I see that—for art—2025 was not bad at all. Stunned, 2016-style topical responses are long gone for the most part; the most meaningful work is characterized instead by a steely, head-down focus on being one’s self and doing one’s thing, undeterred. The (art) world may fall apart, but artists seem a psychic bulwark still. And while there were some let-downs, more memorable were the big moves and great shows. There was even some good news.

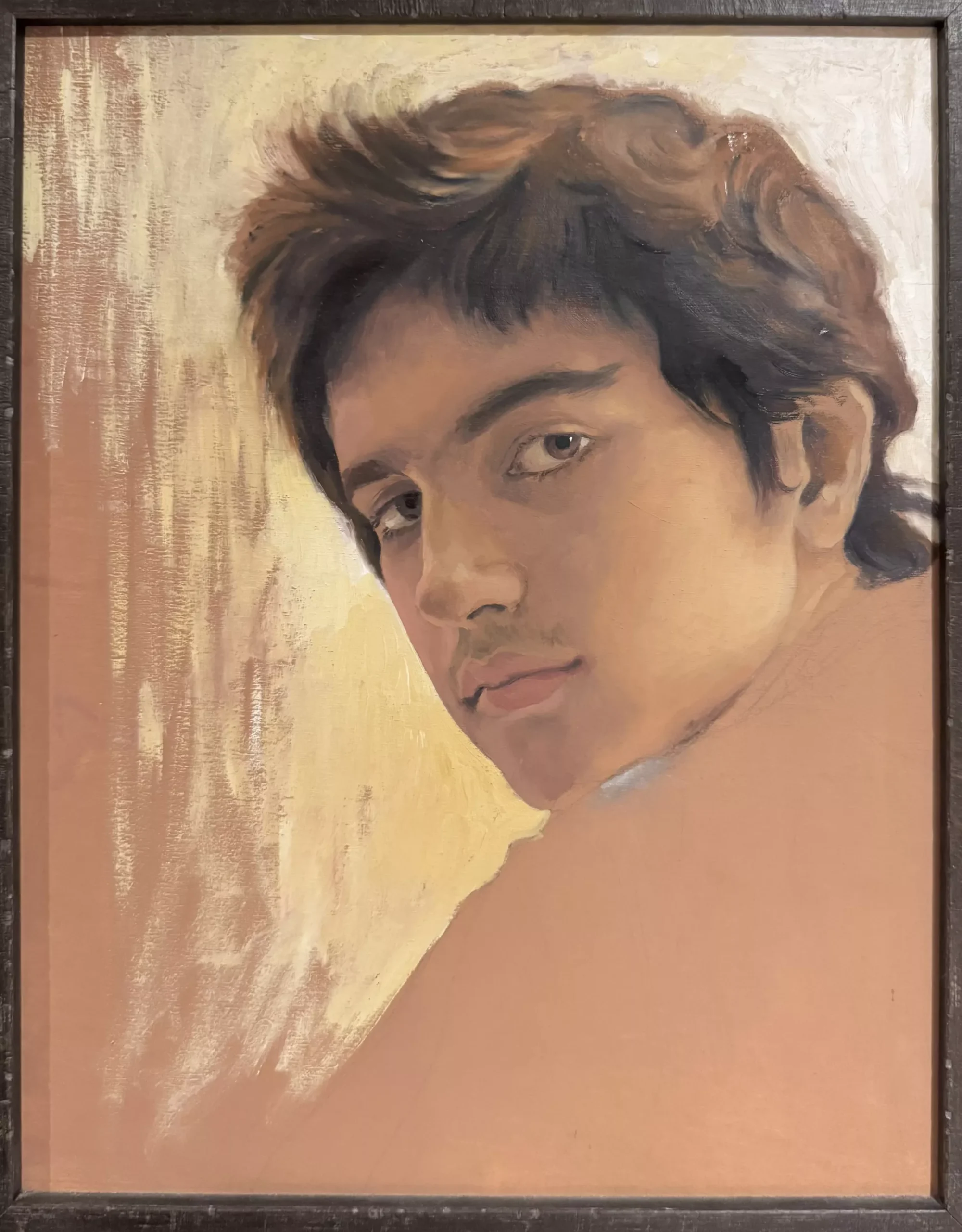

Maybe you’ve seen the Time cover collectively naming “The Architects of A.I.” as the person of the year, with the tech-billionaire usual suspects shown together, perched on a steel beam—House Harkonnen restaging Lunch atop a Skyscraper. But here in New York the person of the year is—hands down—our mayor-elect. When a 2007 portrait of Zohran (then 14 years old), by none other than one of this year’s most celebrated painters Salman Toor (then a Pratt MFA student), surfaced on social media last summer, it clinched the sense of destiny surrounding the young politician’s meteoric rise and underdog victory. It did for me, at least, as a fan of both artist and subject. (See below for more on Toor’s bravura two-gallery presentation, which opened in May.)

With a transition committee that includes Legacy Russell of the Kitchen and MoMA PS1’s Ruba Katrib among its esteemed members, and—over the weekend—such pre-inaugural stunts as a durational listening session at the Museum of the Moving Image in the spirit of Marina Abramović’s 2009 MoMA smash, a Mamdani administration seems promising for the arts, though perhaps that’s overthinking things. What’s good for the cost of living, for immigrants, for childcare, healthcare, housing, etc., is good for artists, art workers, and an art world that’s more than a pleasure garden for the ultra-rich. And can’t you just see Toor’s glowy headshot-composition of Zohran framed by the Time’s signature red border?

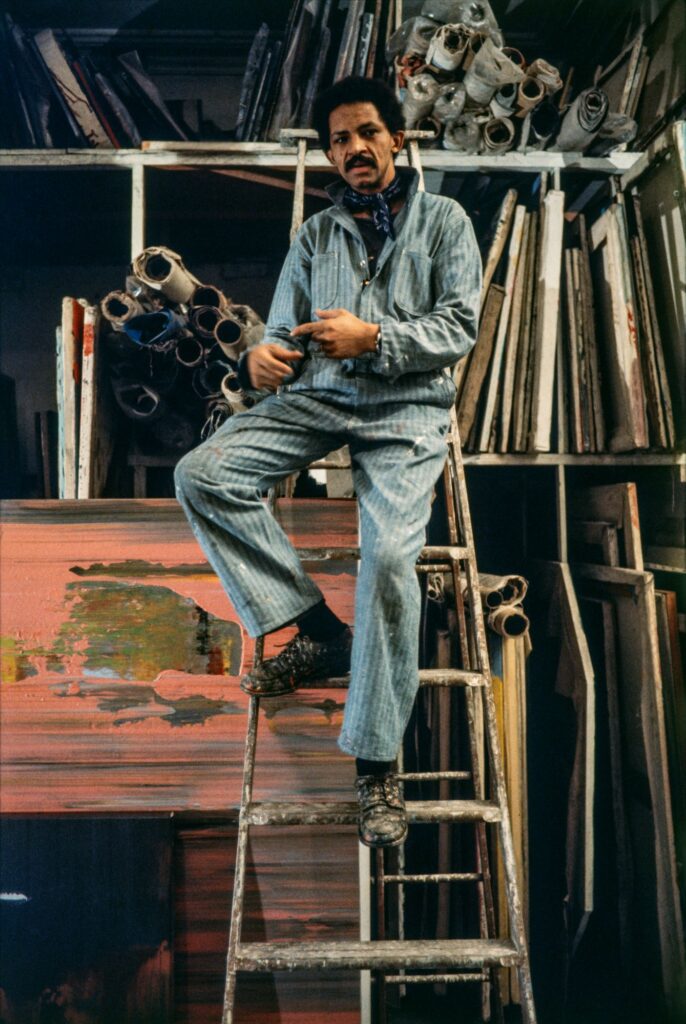

“Jack Whitten: The Messenger” (at the Museum of Modern Art; organized by Michelle Kuo with Helena Klevorn, Dana Liljegren, and David Sledge)

We all seemed to agree, with fervor and conviction, that Jack Whitten’s survey was perfect—except for its timing, of course (some seven years after his death). A procession of superlative, tough paintings that cite jazz as a formal model for material experimentation, and Black history as a muse, showed his visionary scope and tenacity; archival materials, including his tools (such as the enormous rake-like “Developer” that he dragged across canvases) and his studio journals granted insight into his process and his restless self-reflection as he pushed himself into new artistic terrain. As a long-ago painting student of Whitten’s, I found the show to be both very beautiful and pretty shattering. Only a small portion of this tremendous—and, until recently, under-sung and under-shown—body of work was visible to me when I knew him in the late ’90s.

Anne Imhof, DOOM: House of Hope (Park Avenue Armory)

In part, it was the lack of consensus here that made Imhof’s epic production so compelling, its afterimage prolonged for me by a series of chaotic, vacillating text-thread analyses and opinions exchanged with fellow attendees afterward. Unfolding over three hours in the Park Avenue Armory’s drill hall amid Jumbotrons and a sinister fleet of Escalades, with a cast of 60 or so (ballerinas, skaters, models, actors, and more) and an intricately collaged reverse-Romeo and Juliet story arc, it was a commitment—an investment of time that seemed to breed grievance if you weren’t hit with that final-act euphoria many of us felt. Some were fatigued by the rough-around-the-edges spectacle, and then by the parade of takes. Not me, I loved talking about it.

Laura Owens (Matthew Marks)

The Los Angeles-based artist’s return to New York was another notable big swing, much discussed (though not nearly as debated as Imhof’s) in my circle. In room-blanketing installations across the gallery’s two 22nd Street spaces, Owens layered 19th and early-20th-century-inspired wallpaper prints, accompanying them with tall, neo-Orphist canvases in Laura Ashley hues and an arsenal of trompe l’oeil techniques. The 360-degree designs were studious and painstaking, but also, in flashes (or cartoony splashes), they recalled—strangely—Katharina Grosse’s forceful, environmentally scaled gestures and improvisations. Arriving as Owens’s show did toward the beginning of the year, in February, I thought it might be a harbinger of things to come for abstract painting. Not so much. More notably, a few established figurative painters upped their game

Salman Toor, “Wish Maker” (Luhring Augustine)

The Pakistani-American painter’s new work has progressed from tighter, more narrative work that casts queer immigrant characters, like himself, in contemporary scenes—in apartments and bars or on the street, bathed in absinthe light, in a style equal parts Rococo and Van Gogh—to something still recognizably his, but with a murkier beauty and depth. My favorites: Skinny Boy, 2025, whose slightly goofy and apparitional subject holds a phone up, FaceTiming maybe, or taking a selfie, his image reflected in a bathroom mirror; the hazy, lemon-sepia picture Mommy’s Room, 2024, which shows an interior from a curious, astral-projection perspective, similar to the vantage in the also figureless, vertical image of an Islamic cemetery—a place for the dead recalled through a child’s eye maybe, quietly gutting in another year of genocide.

Jennifer Packer, “Dead Letter” (Sikkema Malloy Jenkins)

Mourning and memory lend Packer’s breathtaking show its slowed, otherworldly temporality. (“Dead Letter” is still on view for another moment, until Dec. 20.) The painter grapples with the loss of her partner, the poet April Freely, in a suite of variously legible, sometimes devastatingly effaced, figurative scenes, punctuated by small still lifes—bouquets alternately fading or bursting with fresh-cut vivacity. In the high-key red-and-blue Warp, Weft, 2025, with its veils of paint thinned with turpentine, the drip seems a metaphor for something (or everything) slipping from our grasp.

Vaginal Davis, “Magnificent Product” (MoMA PS1; organized by Jody Graf and Sheldon Gooch)

You have a few months left to see the living legend’s triumphant retrospective—make every effort to get there! “Magnificent Product” tracks Vaginal Davis’s production from early performance work and zines to her makeup paintings, bread sculptures, and installations, showcasing her ever-expanding, louche and frilly, queer-Black cosmology of pop-cultural detritus and fantastic invention. At the opening with a group of buoyant friends, who’ve likewise watched Davis’s progression from punk royalty to queer-theory darling to whatever formidable and fêted force she is now, one whispered to me, looking around, “This is almost… too good.” And perhaps that sums up 2025: When good things happen, we hold our breath, waiting for the other shoe to drop.

And now for the disappointments. Well, there was that Taylor Swift album; I realized I’m just not into Caspar David Friedrich; and, in truth, Time is not wrong—the so-called architects of A.I. did define the year in many ways. If there’s an artifact of visual culture that says it all—emblematizing the state of national discourse, the unmasked gutter-racist flipside to MAGA neoclassical aesthetics, and Silicon Valley’s fascist turn—it would have to be that deepfake the president posted. You know, the one where he wore a Burger King crown to dump shit on protestors from a fighter jet. The medium is the message indeed.

While artists employed the technology inventively and critically (I don’t mean Beeple’s red chip spectacle of billionaire-faced dogbots at Art Basel Miami Beach, but rather, work like Tishan Hsu’s hyperreal post-corporeal show at Lisson, or Sarah Friend’s performance-based investigation of consent in the era of the prompt, both covered by the Critics’ Table), others didn’t engage with the paradigm shifts—sometimes at their peril.

Flora Yukhnovich’s site-specific, wraparound mural at the reopened Frick, reinterpreting François Boucher’s Four Seasons, fell flat because it looked like A.I., an immersive, decorative “riff” on something, which is one of the technology’s familiar fortes. Luc Tuymans’s work, which once felt so eerily trenchant in its observation of our mediated reality—with its faded, unstable, straining renditions of photos—hits differently now. In the painter’s most recent show at David Zwirner, his approach to the image seemed outpaced by new modes of filtering and recombination, and a post-truth perceptual baseline—though I loved the fresh, allegorical character of his maggot. So, maybe I take my thumbs-down back. The flaccid phallic parasite with its cloudy Harkonnen vibes is an apt mascot/memento mori for a mostly revolting trip around the sun. Scroll back to the top of my list for a better image to get behind as we start the new one.

in your life?

in your life?