Once upon a time, before the Covid-19 pandemic—before I was married, before I was pregnant—I visited the painter Loie Hollowell’s studio in Queens, with our mutual friend, Haley Mellin. I was taken with the scale and symmetry of her abstract, geometric works, but also with her ability to wrangle her then-toddler, who was running around the space as we appraised the paintings. At five months pregnant myself now, and grappling with what that means for my identity, I thought there was no better person to speak with than Hollowell, an artist and mother whose entire project explores the female body.

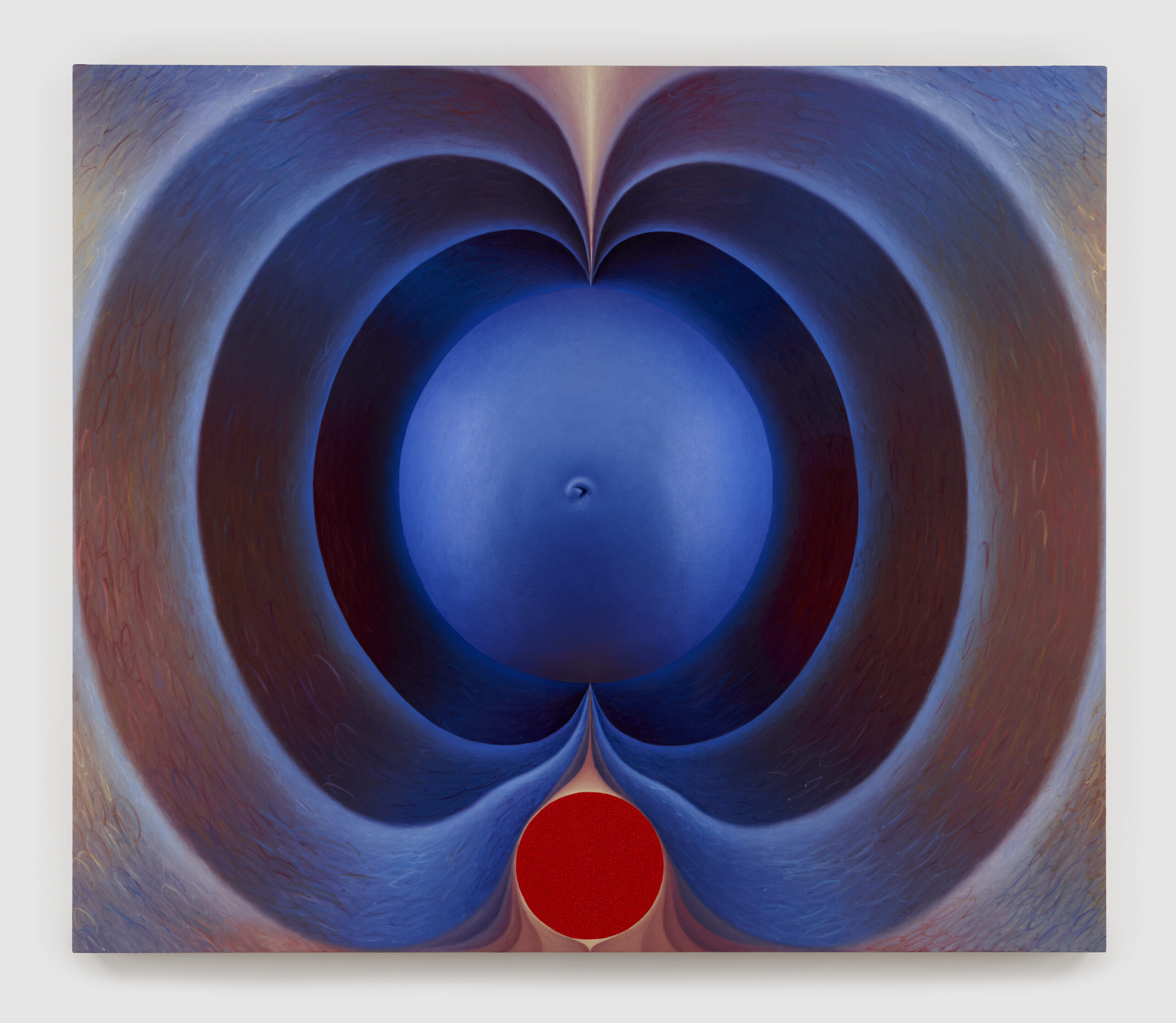

Now a mother of two, the artist paints from her own experiences within her body, drawing on pregnancy, childbirth, and now, perimenopause. Last year, the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Connecticut presented her first museum survey, “Loie Hollowell: Space Between, A Survey of Ten Years,” which mapped the parallel evolutions of her visual language and her body. I spoke to Hollowell about her studio practice and sought her counsel on what to expect while I’m expecting.

Being pregnant has taken over my being. I’m five months pregnant now. I was thinking about artists who have portrayed that, and artists I’ve met who are moms. I remembered going to your studio and your child running around. It felt like a good match for a conversation right now.

It is so important, those early examples of what the future could be, and seeing women who are a little bit ahead, doing it in a way that’s like, “Oh, okay, I can do this.”

And the fact that you had a second is only better for me because it shows that not only can you handle the first, but you decided to go for the second.

Yeah. How old are you?

I’m 32.

Okay. So I had my first at 35 and my second a year and a half later. I’m finally at the place where I could visualize having a third, but I’m already going through perimenopause, so I don’t think it’s in the cards for me.

I don’t know if you felt this way, but pregnancy right now feels like an attack on my body, and my independence, and who I thought I was. I’m having [the thought of], Okay, I’ll never be the same. What’s your perspective on that?

I mean, on a cellular structure, you’re not the same. Your body is physically morphing to make room for this baby to come out between your pelvis, reshifting all your symmetries. Mentally, you’re not the same. The thing I hadn’t expected was the feeling of living in fear all the time: the fear of the loss of the pregnancy. And then when you have the baby, not only are you scared of accidentally doing something to your baby, but also obviously the fear of losing your child.

Do you think that you were expressing that fear and anxiety through your work while you were pregnant?

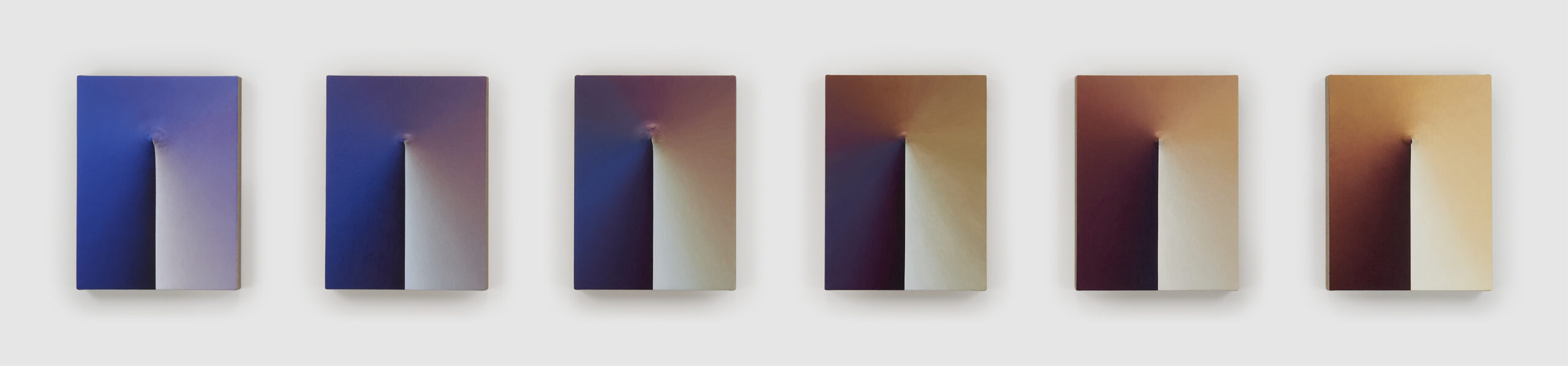

No, I didn’t express that fear through the work. The major shift that was evident in the work was the physical change that happens in the body, the physical realignment. I explored that in the show that I did with Pace [Gallery] in New York in 2019. I called it “Plumb Line.” The plumb line has a plumb bob at the end, and it’s an ancient architectural tool, used to find the perfect vertical. For building a wall, you need a perfect vertical. So I was thinking about that as a reference point for that work, and the falling apart of my body was more present when I was pregnant. Once the baby came, the fear was just so all-encompassing that I haven’t quite figured out how to put it into the work. It’s such a primal feeling.

It feels like that is an experience that a lot of women have, just the focus on what’s moving and changing.

That keeps happening even when the kids are growing. Everything changes so quickly. Their development and the way your brain is restructuring based on your personal history of being a kid with parents, and then how you want to parent. You’re constantly grasping for a new identity and a new relationship that you’re trying to build between you, your partner, and your baby each day. There is almost no time to sit and analyze it theoretically or conceptually because you’re grasping for each day to go well. And I think only now, when my kids are 5 and 6, that I feel like I could really look at that feeling of fear that I had.

You’re just coming out of the grasping-for-breath phase.

Yeah, to actually look at it objectively and make art about it. But the physical things I’ve always made work about at the time. The work that I did at my first show at Jessica Silverman two years ago, with these big pregnant bellies—those were physical explorations. But exploring the mental stuff is really tricky. We’re both lucky that we have partners. But that creates a whole other dynamic.

You have such a specific relationship with the baby before your partner meets the baby. Two becomes three, but the two have had so much longer together. That is also something that I’ve been thinking about a lot.

There’s something beautiful in watching your partner become a parent in a real way. But there’s also, for me, little bits of jealousy, and I know best. Letting go of that was when the really beautiful things happened.

Is there any art that has triggered or inspired some of your ideas of motherhood?

Before I met my partner, I really wasn’t thinking about having kids. I had thought about it, actually—I got an abortion, I didn’t want kids. I didn’t have a lot of role models who were artists and parents. There was one major one: Robin Hill. She’s a professor at UC Davis, where my dad taught. She made that visual possible. In grad school, there was a woman who was a tenure-track professor who was a few years older than me, who had a kid, and ended up really having a hard time. She did end up leaving. So that was a scary example. But once I got pregnant and was trying to grapple with the emotional state of it, there were a lot of people that started coming up for me. The fear element was visualized for me with Käthe Kollwitz. From the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th century, she made woodcuts. Do you know this work?

I don’t actually, but now, I’m curious.

Also, Monica Sjöö. She made these political paintings in the late ’60s. There’s one called God Giving Birth from ’68. This will make you feel very powerful. Also, a really good show right now is “Designing Motherhood” at the Museum of Arts and Design [in New York]. It’s about designs that help facilitate the female reproductive system—birth, pregnancy, abortion, birth control—like the first birth control pill, the first pregnancy test, the speculum.

Do you find that there’s a pre-motherhood you as an artist, and then an after?

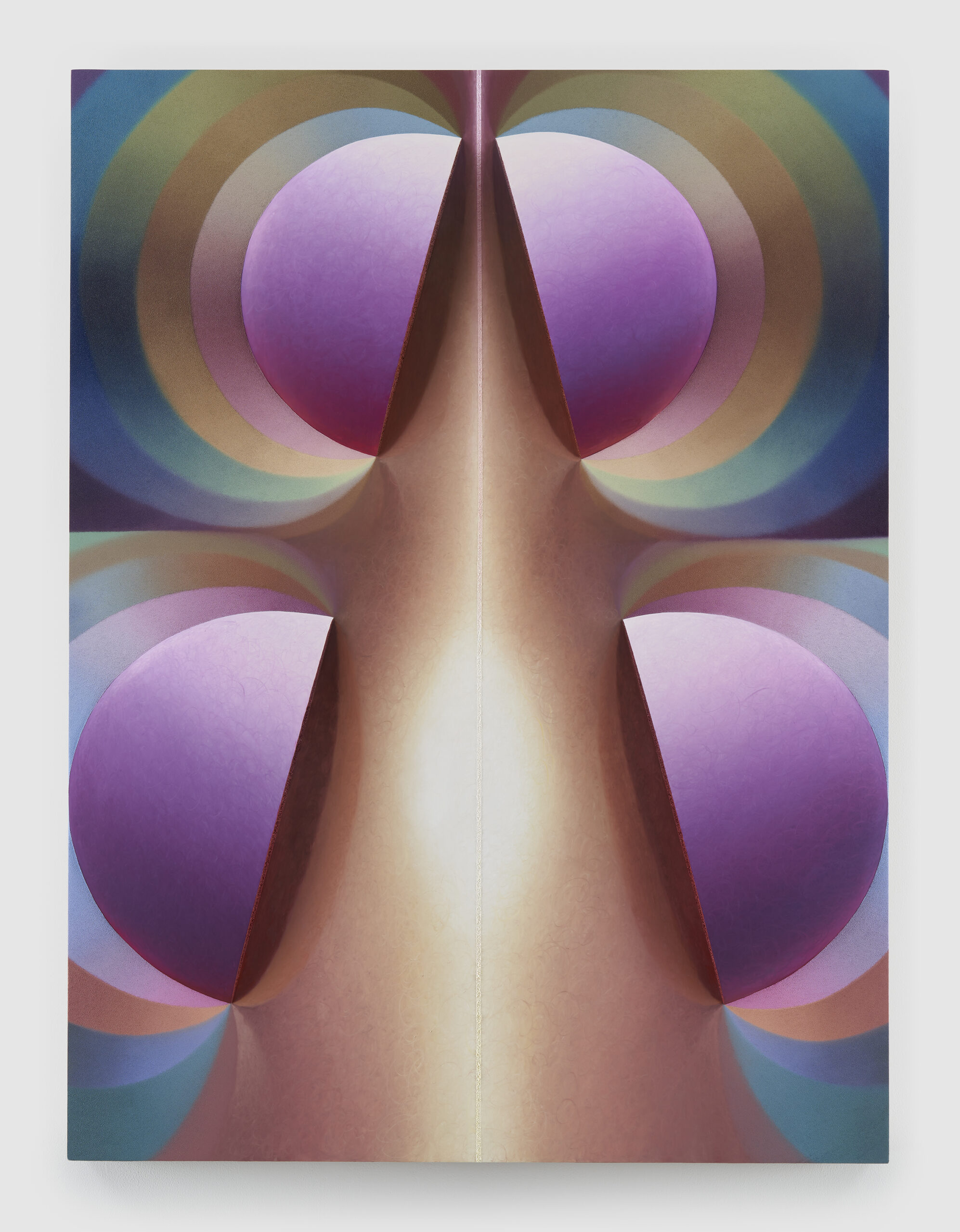

My whole project is exploring the body. There are endless amounts of changes in the female body, even when you don’t have kids. As you age, there are beautiful, cyclical things that could be explored. How can I make work about perimenopause? And the loss of a cycle, the unrhythmic-ness of a new uncertainty in the body? It’s a new identity, almost.

When you look at your work, you see such a dedication to understanding the body.

If anything, [motherhood] complicated my relationship to my practice. I had this really structured, tight visual aesthetic. And then when my boobs were just pulsating in pain with mastitis and milk goo everywhere, and the bigness of the belly, and the flabbiness of the skin—there was something so physical about that experience that I had to capture it physically with body casts. Putting those cast elements into the work took it out of the realm of geometric abstraction and into the physical, the didactic. That was just so different from what my practice had been.

It sounds like it’s not the idea of having a child that has influenced your work, but just the natural ebbs and flows of the female body and the female experience. So now that you’re in the perimenopause phase, that’s still such a personal experience.

Unlike pregnancy, over 50 percent of the population will go through menopause. With pregnancy, we theoretically have a choice, but menopause happens to us. That’s something that is very exciting for me to create art about.

How have you personally experienced being a parent in the art world?

I have to say, not so different from just being a parent in the world. I love hearing people’s birth stories, pregnancy stories, and child-raising stories. I probably wouldn’t have had those conversations [in the studio] if I weren’t making work about it.

If you could give one piece of advice to a new mom, what would you say?

Oh my God.

It doesn’t need to be profound. It can be very silly.

Don’t beat yourself up. Any way that you have to make stuff happen is okay. If you have to give your baby formula, that’s okay. If you need to sleep separately from everyone, that’s okay. Just figuring out how to make your brain feel less like you’re going crazy is the most important thing. And don’t let idealized parenting stuff get in the way of finding any form of self-care.

My mom gave me the exact same advice.

Oh, really? With the first, they said he had a tongue tie. And I happily started pumping, and I went to a separate room every night, and I pumped, and I put my milk in a fridge in the hall. My husband came and fed the baby at night, and I therefore got sleep. My husband had an experience being this crucial feeder. Before, I was pushing myself: I have to give him the milk from my breast. And then when the milk wasn’t coming in, I was too scared to give him formula because I had so much stigma around that. And all of those things were fine.

Thank you for this. I’m nervous, but excited, and I think professionals in my world make it all seem a little bit more possible.

The time just really does go so slow and so fast. And in the hardest moments, tell yourself you’re going to get through it. It literally, the next day, could be totally better. The next hour could be better.

in your life?

in your life?