“To young artists, I always say, ‘Do not give up,’” Howardena Pindell told the audience at the American Federation of Arts’s 2025 Gala in November, where she was honored with a Cultural Leadership Award. The lesson is one Pindell learned the hard way, working as a Black woman in a largely white and historically male-dominated art world, facing hostility and racism throughout her career.

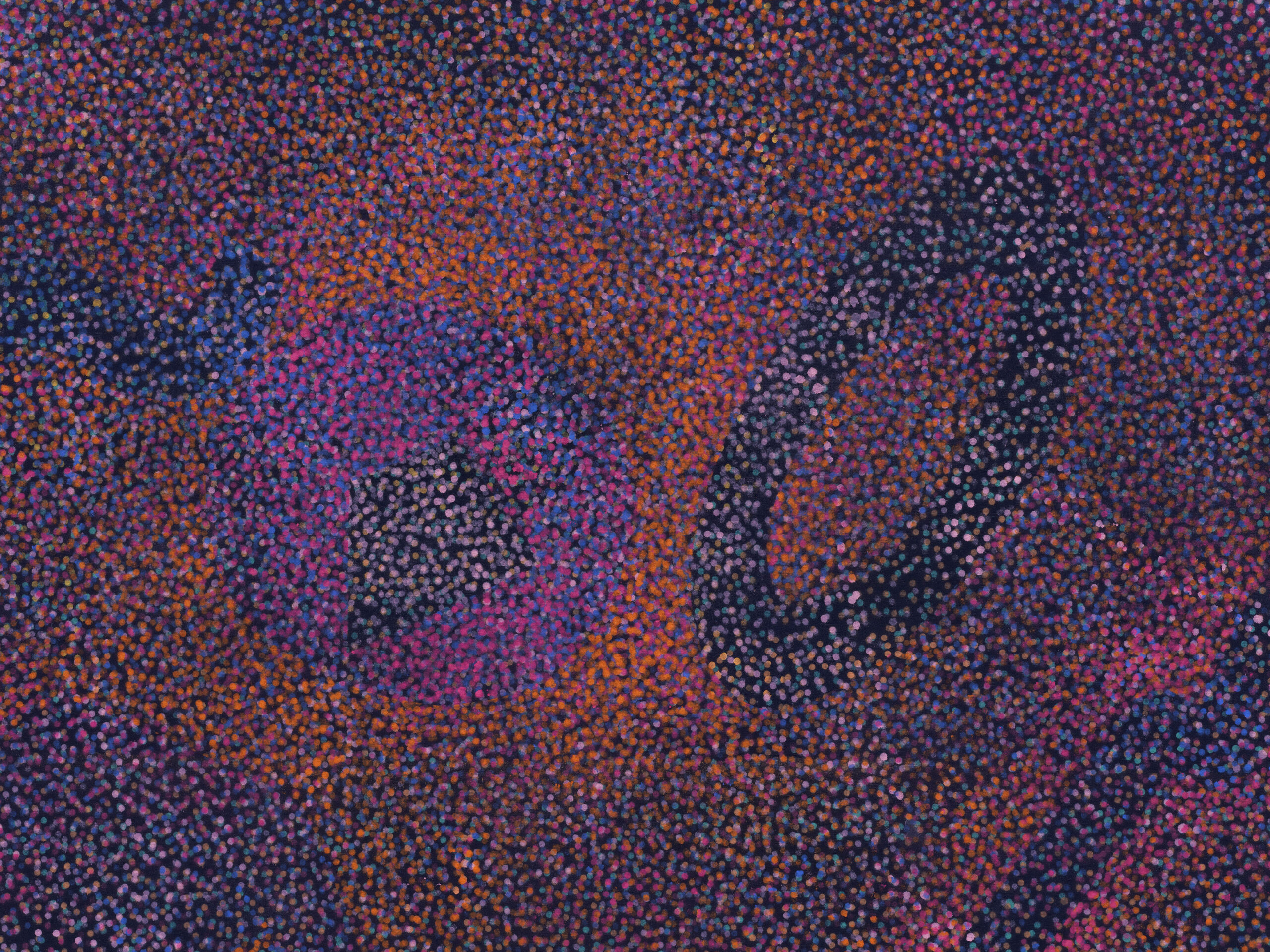

The dots that are so prevalent in her work today are based on a memory from her childhood, when she stopped with her father at a root beer stand in Kentucky and the bottoms of their mugs were stamped with a red circle, to distinguish them from those used by white customers. She was the only Black student in her BFA program at Boston University (1961-65), where she trained as a figurative artist, and among just a few Black students in her MFA program at Yale (1965-67).

When she moved to New York after her studies, she had trouble finding teaching work due to discrimination, but she was able to get a job as an assistant curator at the Museum of Modern Art, where she worked for more than a decade. Again, she was the only Black woman in the role, and left the museum in 1979 to focus on her art practice and teach at Stony Brook University.

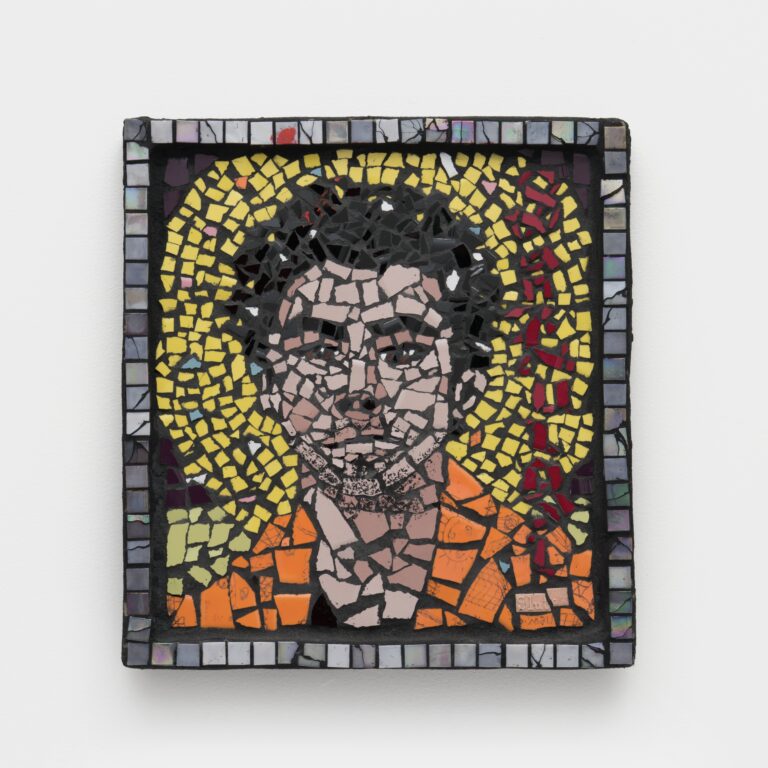

Her landmark video, Free, White and 21, 1980, encapsulates her experience of everyday racism in the art world and throughout her life, from the kindergarten teacher who tied her down with bedsheets to prevent her from using the bathroom, to the well-coiffed white women who called her “paranoid” and “ungrateful” and discounted her work. None of that made Pindell give up, and today, at the age of 82, she is widely recognized as both an incisive artist who takes on challenging subjects, as well as a master of color and form. Her oeuvre navigates fluidly between more figurative and narrative work and pure abstraction, raising questions about why the art world insists on siloing these approaches.

White Cube currently has a show dedicated to her decades-long career, “Off the Grid,” on view in its Bermondsey, London flagship through Jan, 18, with earlier work hanging alongside new abstract pieces. She has also been commissioned by the University of Texas at Austin to create a 50-foot-tall stained-glass mural for its College of Education’s new George I. Sánchez building, opening next spring. Dia Beacon acquired a suite of her works that will go on long-term display at the end of 2026, and Pindell is also the only living artist in the AFA’s nationally touring exhibition Abstract Expressionists: The Women.

We caught up with the artist from her home in the Bronx about the podcast that keeps her up to date on the news, a formative studio visit with Helen Frankenthaler, and why she would be terrified to win a Nobel Prize right now.

How did your show in London go?

The show seemed to have gone well, there were some pieces I wish they had, but then they showed some of them at Art Basel [Miami Beach] down in Florida.

Which were those works?

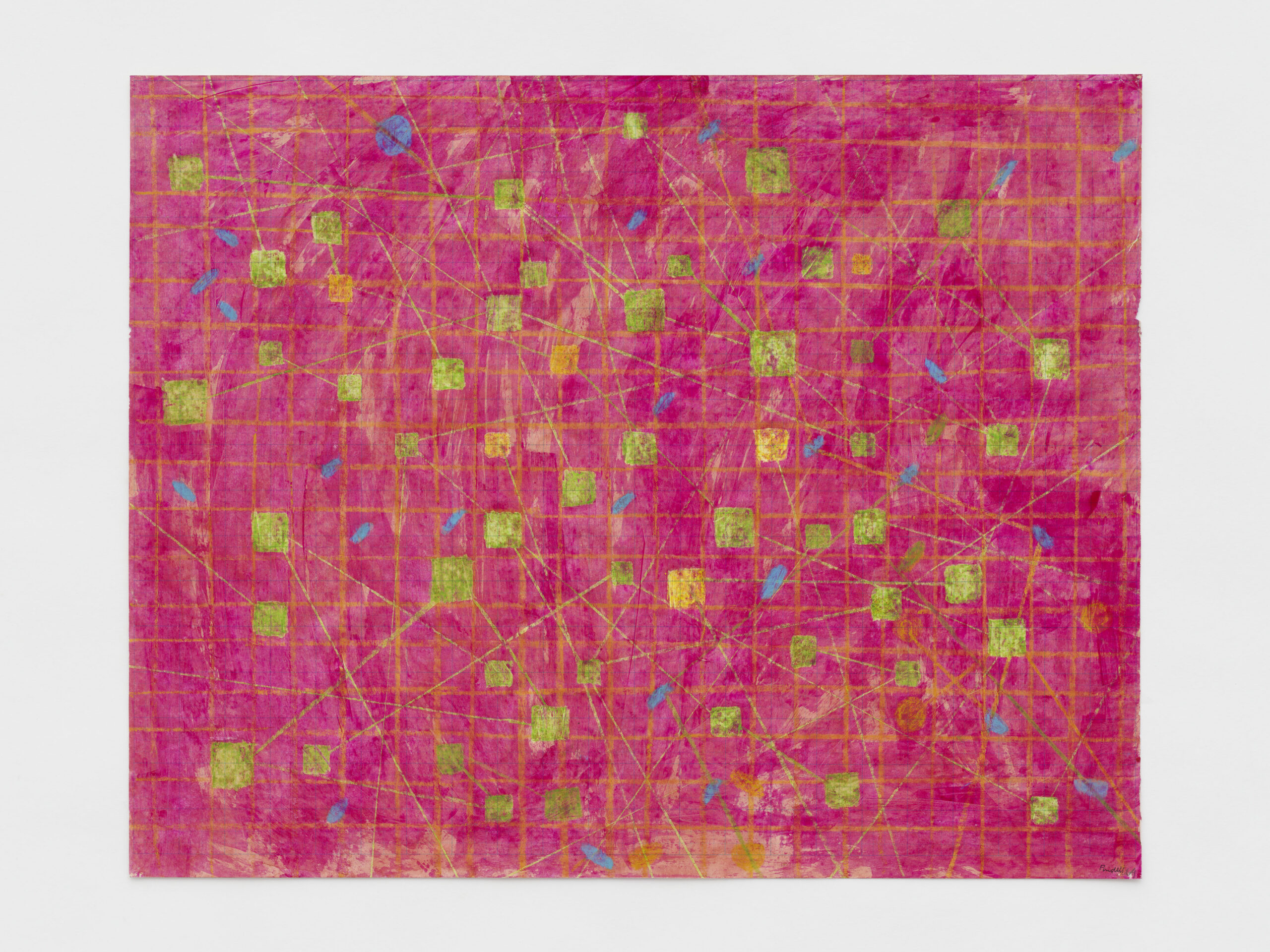

Well, the one work that I really, really wanted, I call it a Tesseract [#29, 2024]—geometric shapes floating in the cosmos. It has pinks and yellow, it’s very pastel, and it’s so unlike the other pieces. Otherwise, the show covered a lot of stuff. It was amazing to have it all spread out like that, that was great.

They also showed three of my films—and there’s some tough ones. Rope/Fire/Water, which is about lynching, and Doubling [which is about war atrocities]. Especially if you think of what happened to those people on the boat [destroyed in the Caribbean Sea during a U.S. military strike on Sept. 2].

I think under Trump, it’ll be hard to find a venue willing to risk [displaying work like Rope/Fire/Water], because it’s about lynching, and he doesn’t want to think about lynching. It’s so funny, this is going to sound so strange—because I have gotten a fair number of awards, but I thought to myself, “Oh, my God, suppose they gave me the Nobel Prize, he’d have me killed.” I mean, I’m not going to get a Nobel Prize. But anybody actually, especially someone Black, if they got a Nobel Prize, and he doesn’t get it, I can imagine just all the horrible things that will happen to them.

It’s difficult to have somebody in power with such a fragile ego.

Do you ever listen to MeidasTouch [the progressive podcast and news program started by lawyer Ben Meiselas]? It’s very good. He gives daily reports about whatever he feels like talking about, and then sometimes he’ll interview people. But mainly it’s him touching stuff that most people would be afraid to.

You clearly stay very connected to what’s going on, politically and socially.

I am not someone who can turn away. MeidasTouch keeps me in contact with some of the more current things. But I also watch Trump’s cousin [Mary Trump], who’s a psychologist who analyzes him. And then there’s Robert Reich.

How do you process what’s going on in the world as an artist?

I haven’t done an issue-related piece since Rope/Fire/Water, I’ve mainly concentrated on the abstract pieces. I just do not want to draw attention to my work from the MAGA people. I think the best way I can handle it is to just keep track of my ideas, and then, if ever the black curtain lifts, I can get back to some of the issue pieces.

You faced so much resistance as a young artist, and you’ve persevered for so long. What’s it like getting recognition at this stage in your life?

I don’t feel it. I know that sounds strange. I’m puzzled. When I got up to go on the stage [at the AFA gala], there was a standing ovation. I hadn’t said a word yet. And then when I finished, I said: “Don’t give up. And I think that applies to people who aren’t artists in our current political climate, let us not give up.” And everybody very demurely applauded. I think I frightened them.

You also mentioned at the gala wanting to support a residency for artists with disabilities. You use a wheelchair and a walker after knee surgery. How has your experience with mobility issues affected your view of how accessible the art world is?

I’ve been thinking through it, because I think it’s better that we be in the same facility, like the MacDowell [residency in Peterborough, New Hampshire], rather than be separated. MacDowell was very good. When I was there [in 2008 and 2013], I was using a cane, and I didn’t want to be on the first floor, because they’ll talk to you about bears. I had to go up a long flight of stairs to get to the second-floor bedroom. But I can’t do that anymore.

My dealer [Garth Greenan] wants to buy me a wheelchair-accessible car. Saturdays I normally go to the Met. I take my health aide, and I also take a friend with me, it’s just easier because I have the wheelchair and the walker. And there’s sort of a lunchroom on the second floor. So I feed all of them. We go off for three or four hours.

You have talked about the impact of visiting museums in Philadelphia as a child, when you saw a portrait on an Egyptian mummy that resembled you.

My third-grade teacher, Mrs. Oser, said to my parents, “You need to take your daughter to the museum. She’s very talented. She should meet artists. She should go to the museum and galleries.” My parents introduced me to white and Black artists, male and female artists, and I was sent to Saturday art classes when I was eight. And without that earlier beginning, I don’t know [if I would have become an artist]. I’d love to have been an attorney for the ACLU, but my brain isn’t that bright.

I disagree. You also were really drawn to the work of Marcel Duchamp.

The Philadelphia Museum had a section for him. My favorite, Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? [a 1921 readymade sculpture of a birdcage holding small blocks of white marble resembling a pile of sugar cubes]—I love that work, and the fact that he would dress up as a woman and also take a woman’s name. I liked the Renaissance paintings there. And I kept trying to paint like a Renaissance artist, which, of course, I failed miserably at. Ironically, when I was at Yale as a student in the art department, Helen Frankenthaler was a visiting critic, and she came by my studio, and as she left she said [somewhat dismissively], “That was done in the Renaissance.” I realized later I should have said, “That’s pretty good.”

But years later—it’s even funnier—when I was working for MoMA, I was sent as a liaison to meet her, because we were thinking of doing a joint show of her work. And I thought she’d faint when she opened the door and [was so surprised to see] me representing the museum.

What other projects are you working on?

I applied for an MTA project at the New York Botanical Garden [Metro North station in the Bronx], it’s an outdoor station. So I photographed the garden. I’m very excited about it. When I was much younger, I used to go to the Botanical Gardens or near there, and I would feed the squirrels when it was really cold. I’m an animal fanatic.

The project for the station is stained-glass. I’m really excited about that part of it. I did another stained-glass work for the University of Texas. It’s circles in different colors, some with numbers.

You’ve been a professor for so much of your life, a school environment must be very familiar to you.

Forty-three years. I don’t miss the committee stuff. I liked working with the students. When I first started—in 1979, on Long Island, which is very prejudiced—the students that were the most difficult to deal with happened to be white women. One of our graduate students, who’s Native American, they harassed her, too. But she was a tough cookie, she could manage them. I was so disappointed that you had to watch your back.

And then I was chased by one of the students, a white male, whose father wanted him to go to medical school, and he was demanding that I move his grade from a B+ to an A. He went to the chairman and complained. The chairman said, “I’m not doing anything about that.” I was glad to not have to deal with that sort of thing anymore. But it became less and less prevalent the longer I stayed.

in your life?

in your life?