RISD XYZ is the kind of magazine that you neither purchase nor subscribe to, but which arrives anyway. Most universities have their analog: glossy alumni nostalgia in periodical dress, cheerfully keeping the post-grad umbilical cord intact. My copies usually go straight in the bin, and I’ve made a minor sport of dodging requests from the university to update my address precisely to save myself the trouble. But Alexandra called me up with an assignment: to make sense of how a contingent of Rhode Island School of Design graduates, my peers from a decade and a half ago, helped to define the look and feel of a certain new cultural mainstream. So here I am, knuckle-deep in my stacks. The particular issue I’m looking for features my friend Martine Gutierrez on the cover, decked out in indigenous jewelry against a field of chroma green.

Coming up short led to a two-month stint in my little sauna of an office in Madrid on the phone with former classmates. We reminisced about the 14-foot trampoline that dominated our shared loft, our mercifully un-Google-able dorm-room art-pop EPs, and an unsanctioned dinner at a New York design gallery that culminated in our frantically obscuring the cigarette burns on a lauded designer’s piece with nail polish. These memories became a reservoir to plumb for insight into why a particular institutional, cultural, and economic moment produced a cohort that went on to exert disproportionate influence on American material culture over the past decade.

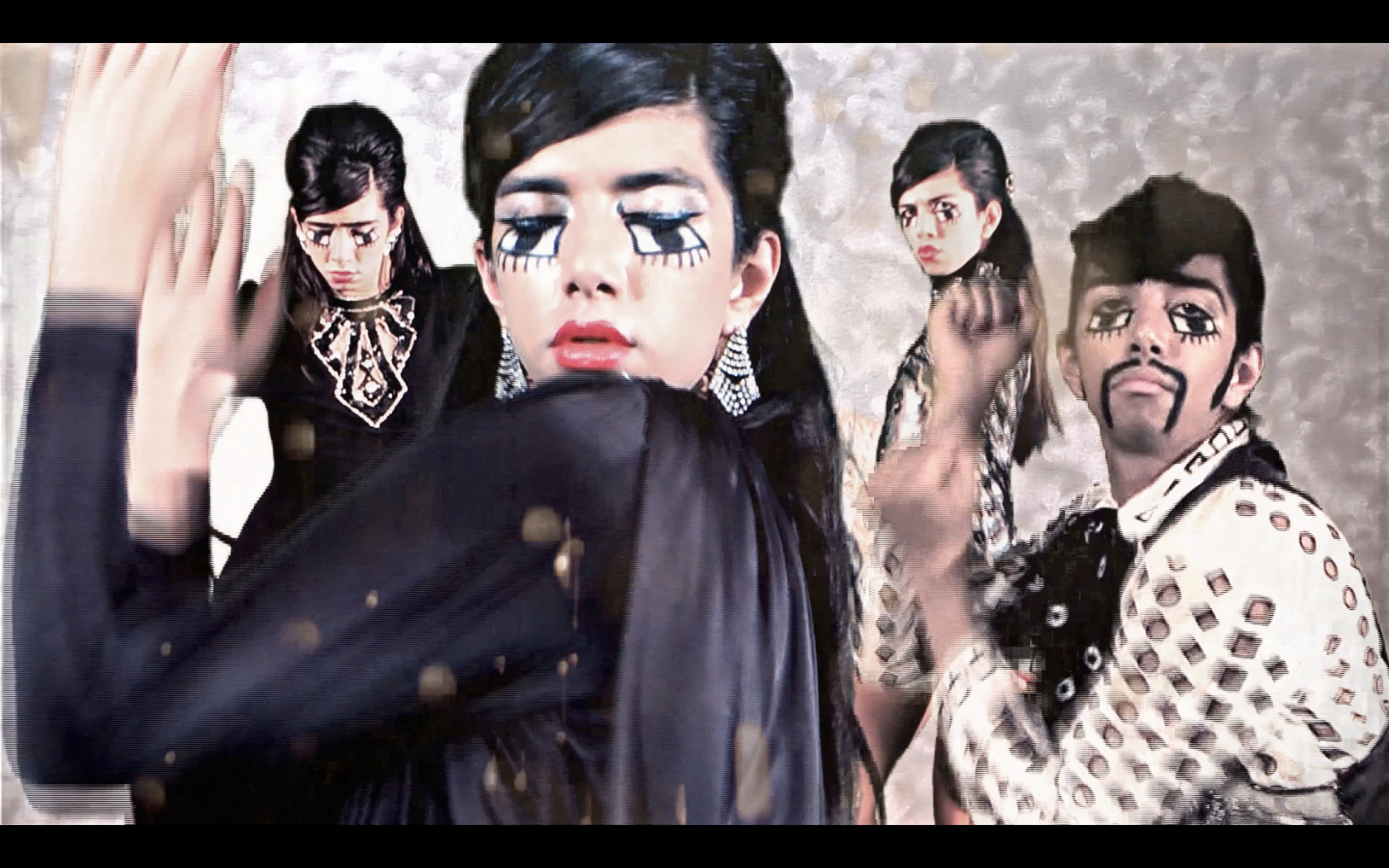

Among them: MIKE ECKHAUS (Sculpture 2010) and co-founder with ZOE LATTA (Textiles 2010) of the independent fashion brand Eckhaus Latta, which anticipated a zeitgeist shift around who gets seen, how, and why. Their approach landed them among a handful of designers to receive solo exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art. ADAM CHARLAP HYMAN (Furniture 2011) runs the eponymous firm Charlap Hyman & Herrero with ANDRE HERRERO (Architecture 2012), a practice that traverses architecture, decoration, scenography, textiles, and furniture. Within a few years, the office has notched five consecutive AD100 nods, an AIAILA Emerging Practice Award, and a Vitra collaboration. KATIE STOUT (Furniture 2012), MISHA KAHN (Furniture 2011), and F TAYLOR COLANTONIO (Furniture 2013)—who operate between design and art, distorting scavenged elements of folk craft, domestic kitsch, and historical ornament into works by turns grotesque, tender, and strangely new—regularly shown in museums and at design events internationally. MARTINE GUTIERREZ (Printmaking 2012) has built a formidable career across art, music, and film, probing race, gender, and media through stylized self-performance, earning a Guggenheim Fellowship, an Artforum cover, and a starring role in HBO’s Fantasmas along the way.1

We overlapped at RISD during a time of institutional entropy and financial collapse. It was 2008: The global economy was cratering, and the school was wracked by internal politicking and bureaucratic inertia. In constant tension between its reputation as one of the best art and design schools in the country and its internal dysfunction, RISD clung to traditional expertise even as the world outside its classrooms was rapidly changing. Departments struggled to hire faculty who had both contemporary relevance and a capacity to teach, and struggled even more to retain those who did. The presidency turned over twice: A famed technologist intent on “STEM-ing” the curriculum was removed in a vote of no confidence. His interim replacement was too busy stabilizing to provide meaningful structural reform. Tuition, meanwhile, continued to creep higher than most graduates could plausibly repay, and the school developed a reputation for lean financial aid.

I’ve come to think of this period as mired in curricular drift—wherein the absence of agile instruction, market preparation, or coherent pedagogy inadvertently created the conditions for autodidactic rigor and experimental range. In the Furniture department, for example, the studio furniture ethos of the 1990s still had a stranglehold on the faculty and curriculum. For most of the professors, woodworking was both fetish and religion. Katie calls it “vocational school.” I call it “carpentry school”: hours spent cutting dovetail joints and studying the splendors of domestic hardwoods, blissfully unaware of the systems and industries shaping contemporary design. But for what RISD lacked, it also offered time, tools, and unstructured access—conditions increasingly rare in contemporary higher education. It was this permissiveness that enabled many to find their own routes. Mike followed his interests to the Textiles department, where Zoe taught him to use the knitting machines. Martine used an independent study as a pretext to produce videos. (The resulting work, Clubbing, was recently acquired by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.) Adam spent his evenings in the library scanning his way through issues of Domus, Casa Vogue, and World of Interiors, accumulating an expansive understanding of design history.

Martine says our school days were opportunely situated just before the dawn of “Regurgitation Nation,” her term for the collapsing of culture into a feedback loop where everyone has the same five references because they’re fed the same five references. We were, arguably, the last generation to experience the Internet before algorithms calcified it.

Misha describes it as “a time when cultural style was a void,” when aesthetic consensus seemed less conceivable. In that moment, digital abundance briefly outpaced its prescriptive practices. Curiosity, rooted in self-knowledge, was crucial to discovery—online or off. The search for relevant material to corroborate interests led to radically different understandings of the same fields of study. Adam consumed Josef Frank and Carlo Mollino’s articulated interiors while obsessing over 1950s Vogue editor Niki de Gunzburg, for whom he built a fictional apartment as his thesis project. Taylor’s allergic reaction to Modernist austerity fueled his immersion in the Baroque. Katie became a John Waters disciple.

While cultural inputs diverged, professional options narrowed. By the time we graduated, most of the traditional routes into design departments that promised long corporate careers were stymied by economic downturn and downsizing. This same sense of constriction and desolation sparked the startup boom of the 2010s, producing the countless MBA-helmed, millennial OTC darlings plastered ad nauseam across every subway station. In business and labor economics, there’s a tendency to call this necessity entrepreneurship: Graduates across the board, faced with a lack of conventional prospects, bootstrap alternatives.

In that context, the notion of “just starting something” didn’t feel quite as delusional as it might have in other eras. As Adam puts it, “I feel like I would’ve been as well suited to starting a magazine as a design firm… Which is to say, I wouldn’t have known anything about how to do it, but I would’ve had the capacity to organize my thoughts, understand the intricacies of getting things made, connect hand and mind in nuanced ways, and see the end in the beginning.” The ability to make things—literally, physically—produced the conviction that you could make anything. This distinctly American cocktail, made of equal parts naïveté, privilege, and individualism, combined with an elite studio arts education, gave many the energy to moonlight their practices into legitimacy.

But beyond the stints in fashion and galleries that parlayed into independent studios was what Martine calls the “phone tree,” perhaps the most dependable asset of the post-RISD world. There were so many alumni in New York City that resources circulated promiscuously and without pretense—tools, spaces, introductions—an economy of favors reflective of, if you’ll pardon the cliche-thinned term, a true sense of community. Katie landed her gig at Johnson Trading Gallery through a friend of Adam’s. Misha’s first show, a two-person exhibition with Katie, happened at that same gallery. Martine made regular pilgrimages to the city from her mother’s barn in Vermont, crashing on Kate Fox’s (Printmaking 2012) sofa and borrowing samples from Alexa Day Silva’s (Apparel 2012) office at Calvin Klein for job interviews. She paid it forward by modeling for Katie’s early furniture shoots and walking Eckhaus Latta’s first runway show.2 Andre, an architect and a photographer, shot the lookbook for that show in a shower stall backstage. Misha collaborated with Mike and Zoe on a collection of shoes a few years later. Katie gave Taylor the commission (a mirror for her bedroom) that pushed him to refine his polished cartapesta technique. Adam commissioned, and continues to commission, all three of them for his curatorial and interior design projects.

More than networking or any other closed system of favor-trading, this was collaboration in its most unbridled, non-institutional form. Each individual had their method of working and brought a novel perspective to their field(s). Ultimately, that exchange of ideas and resources,3 cultivated at RISD and fueled by the economic crisis and pre-algorithm Internet, edged those fields outward toward a new aesthetic language: willfully unpolished, borrowing indiscriminately from history and pop kitsch, conflating white glove opulence, craftwork, and gutter scrap. The effect was dissonant but energetic.

The impact of this cohort has been felt across the visual and material language of contemporary American art and design. The work that comes from it has been copied widely and critiqued just as often: dismissed as dilettantish or opportunistic, or else flattened into trends with little regard for its internal logic. What gets noticed is the provocation; what gets overlooked are the material fluency and technical specificity that underpin the output. Critics may bristle at its theatricality or inconsistency; that discomfort can reflect how its qualities resist prevailing taste frameworks, and is inherent to what made the work legible in the first place. Harder to dispute is that it emerged from, and remains tethered to, a shared set of conditions too specific to replicate, and that its influence continues to circulate.

“In retrospect,” says Adam,”The transdisciplinary nature of so many of the practices that emerged from RISD at that time prefigured the wider explosion of dialogue that was coming in our society, pertaining to all things ‘in between,’ multidimensional, and outside the binary.”

Whether a cohort like this could crop up today is uncertain. The early Internet’s promise of cultural decentralization has largely given way to cultural atomization ; shiny fragments lacking the coherence of a common language. The cost of living has spiraled in places once considered key lines of influence, unstructured time no longer exists, and institutions have become more risk-averse than ever. The foundation back then was a shared physical context, a common set of tools and limitations, and an open exchange. Those conditions feel nearly impossible today. If anything, this account suggests that culture-shifting cohorts are most likely to surface in moments of shared constraint—when proximity and cross-pollination can determine the work as much, if not more, than ambition.

- Together, these characters represent just one visible node in a broader network of influential RISD graduates from the period. Zoom out too far and the network dissolves into a sprawl of connections that defies any approximation of tidy cataloguing: [1] Mike and Zoe lived in a Bushwick warehouse with [2] Jessi Reaves (Painting 2010) and musician [3] Alex Field/DJ Richard (Printmaking 2010). Alex co-founded the label White Material with [4] Quinn Taylor/Young Male (Sculpture 2002), which released early records from [5] Alvin Aronson (Furniture 2008) and [6] Chris Sherron/Galcher Lustwerk (Graphic Design 2009). Chris started the trend forecasting ground K-HOLE, famously known for coining the term normcore, with [7] Greg Fong (Sculpture 2009), [8] Sean Monahan (Painting 2009), Emily Segal, and Dena Yago, and later co-founded the creative research platform Are.na. Are.na regularly collaborates with [9] Laurel Schwulst (Graphic Design 2010), a writer, artist, and designer in her own right… You get the gist.

- It’s worth noting that the show likely wouldn’t have come together without the extended RISD universe. Among those involved: producer Erica Sarlo (Furniture 2010); musician Alex Field/DJ Richard (Sculpture 2010); model and multi-hyphenate May Hong (Printmaking 2010); and Raffaella Hanley (Painting 2011) of Lou Dallas.

- This ingrained interdependence is why no definitive list of ‘successful’ RISD graduates ever quite holds; pick out a few and the connecting threads among a seemingly endless stream of contenders quickly unravel the premise.

Order your copy of CULTURED at Home for more stories like this one here.

in your life?

in your life?