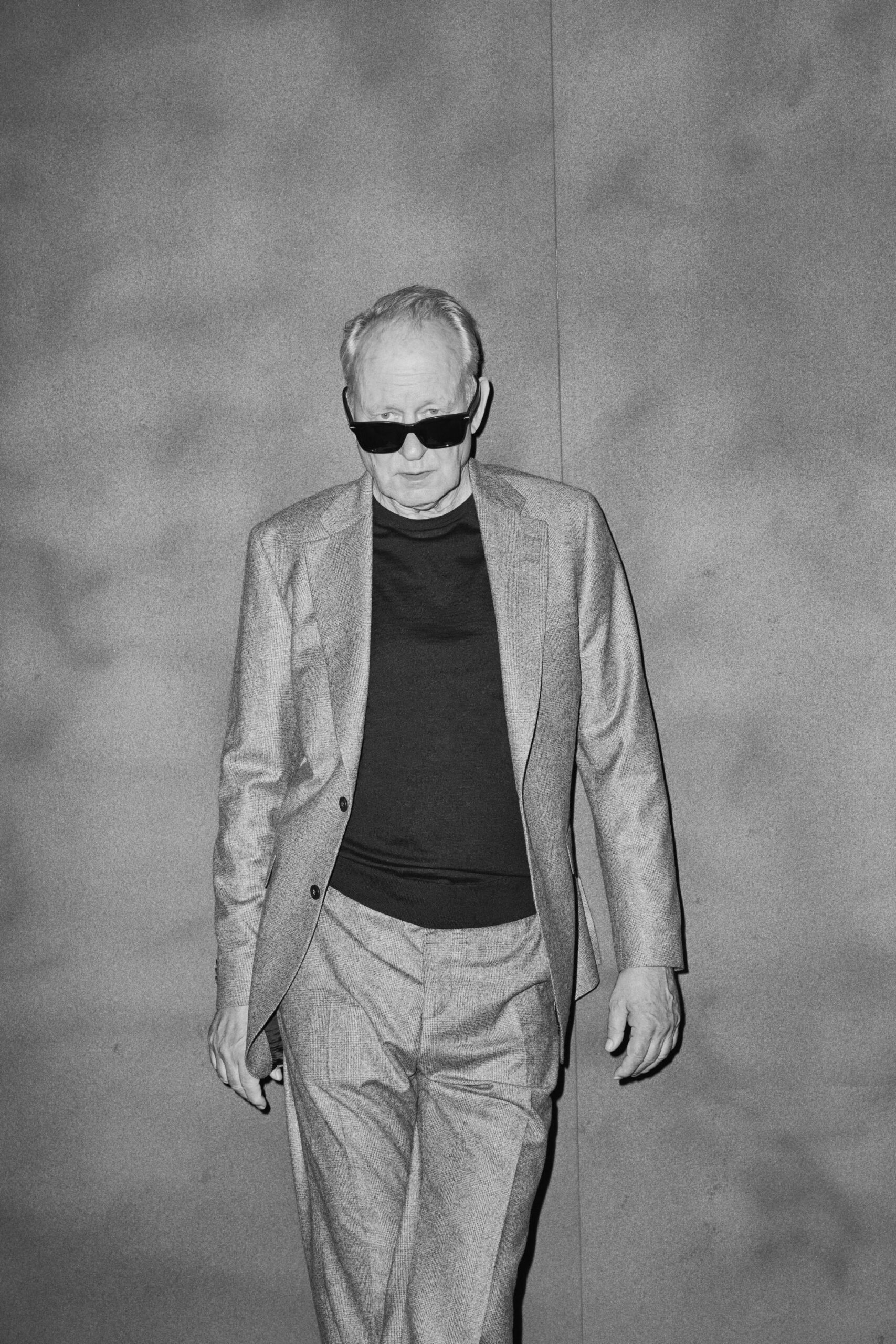

A frigid Scottish oil rig. A sun-drenched Greek isle, awash in a sea of turquoise. An antiques gallery in an alien megacity. Stellan Skarsgård has a gift for fitting in, no matter where he is.

For the last six decades, the Swedish actor has brought a metric ton of gravitas to every role, whether in his taboo-breaking turns with Lars von Trier or levitating from a pit of black ooze in Dune. Despite his willingness to stare into the abyss, Skarsgård has a wry, paternal side. His latest film, Joachim Trier’s Grand Prix-nabbing Sentimental Value, puts his sensitivity on full display, and may just win the 74-year-old performer a long-awaited first Oscar nomination.

Skarsgård, it turns out, also has a strong sense of civic duty. Unlike many others in his position, he speaks with clarity about corporate monopolies and systemic injustice. To the actor, film can be a form of resistance. “Art,” he says, “should be automatically radical.”

So strong is Skarsgård’s commitment to this assertion that, for this Artists on Artists conversation, he asked to sit down with Robert Reich, the former U.S. Secretary of Labor and recent high-profile opponent of the Trump administration. Reich, an economist and academic who has served in the administrations of multiple presidents and built his career on addressing income inequality, has flexed some creative muscles himself. Last summer, he was the subject of The Last Class, a documentary capturing a professor’s struggle to reckon with his own mortality and the broken society that his students will inherit. In August, he released Coming Up Short: A Memoir of My America, which weaves the public servant’s childhood experience of bullying into American narratives of corporate greed, wealth disparity, and political extremism.

Here, the pair discuss the wave of conservatism and demagoguery that has swept across the U.S. and toward Europe—and why there might be a way to turn the tide.

Robert Reich: Stellan, you are very much an internationalist. Sweden has always been a beacon for the notion of common good and social justice. I’m very interested in how you see what’s happened in the U.S.

Stellan Skarsgård: Well, it’s not only in that country—it’s what happened all over the Western world. The big changes started in the ’80s, but the foundation was laid before that. To me, it was unbelievable that people could support the new Chicago school of economic thought [emphasizing free markets and minimal government intervention] and believe that it would work. You’ve been warning them, but politicians went with it. Even in Sweden, the Social Democrats went with it. We had a prime minister at the time who said, “What’s the point? The market rules.” That was a defeatist way of seeing things.

Reich: Obviously, the market is a human creation—very much a creation of government. The question is, How do you create the market?

I was under the impression that Sweden understood this better, even in the ’80s. There’s an easy, straightforward explanation in the United States: You had big money, mostly from large corporations, begin to infect the entire political process, and change the rules of the game and how the market was organized. It created a doom loop in terms of widening inequality and the corruption that comes from it. But Sweden didn’t suffer the same doom loop, did it? Is money in politics as much of a problem there?

Skarsgård: It’s a global world we live in. The moment America gave up and gave in to the market, Sweden did as well. We started privatizing everything.

Reich: I’m old enough to remember the optimism after the Second World War that came with a very large middle class and the idea of a country dedicated to some degree to humanitarian values. The goal was to continue widening the circle of prosperity, so more and more people could ascend into the middle class. The irony is that prosperity may have blinded us to the difficulty of maintaining a democracy.

In other words, you can’t maintain democracy if all you have are individuals whose goal in life is personal acquisition. Democracy requires a lot of attention, a lot of work. It requires a great deal of preservation, particularly in a society where large corporations are becoming even bigger, where there is monopolization, and where labor unions are shrinking. That’s the story of America in the postwar era.

We became too confident. We stopped noticing that the institutions we took for granted were fragile. Donald Trump is the culmination of decades and decades of this carelessness. We allowed the working class in the United States to become understandably cynical and angry.

Skarsgård: I think you point that out very well in your book. When Trump was first elected, I read a book called Strangers in Their Own Land by Arlie [Russell] Hochschild. That was an eye-opener for me. She lived for five years alongside the Tea Party movement in Louisiana. You understood that they felt left behind. It’s frightening reading.

Reich: From here, it looks as though the stresses in Europe are very much about immigration: Immigrants have been used as the vehicle for dividing European democracies, allowing authoritarian groups to gain ground. I think Trump is trying to do the same, but he’s finding that most Americans disagree with the techniques he’s using.

Skarsgård: Sweden is one of the most Americanized societies in Europe. We’re all eating American culture, including me—I love American culture. It’s the non-culture I don’t like. We have a right-wing government now. Already, schools and hospitals were underfinanced, and now we have increased military spending. We are struggling to keep up the welfare state that we created after the Second World War. Even in France, [far-right politician] Marine Le Pen said that there are things that the market can’t take care of: infrastructure, healthcare, education. It’s what the Social Democrats should have said, but they were silent.

Reich: The silence of the Social Democrats, and the Democrats here, has been deafening. The goal of a society must be to reduce fear. One of the great advantages of a country that is investing in its people is that people who are not afraid are less susceptible to a demagogue.

Maybe we could talk about where we go from here. I would like to think that American culture is still very healthy. I visit so-called red states, Trump voters, and most of the time, they’re very kind. They’re not bigoted or hateful. I think people are feeling at the community level a degree of solidarity that I haven’t seen before.

Skarsgård: That’s very optimistic. I’m not that optimistic, but you know more about it than I do because you’re meeting more students and young people. I was very optimistic about Black Lives Matter—it was a force that was unleashed. But at the same time, what did it come up with?

Reich: I think they were co-opted by other groups. Social movements take a great deal of time. Black Lives Matter is still here, it’s just gone a bit underground because the second Trump administration is so punitive. He wants confrontation, and people are smart enough not to give it to him.

In a parallel way to Black Lives Matter, #MeToo went underground. It’s not as active as it used to be. I don’t think the time is exactly right now. But it’s still there. The young people that I deal with every day have absorbed these movements. If I can give the entire structural movement a name, it would be “no more bullying, no more brutalization.” The powerful are no longer going to exploit and oppress the weaker.

Skarsgård: But how do we make concrete demands that are not divisive?

Reich: What progressives need to say over and over again is “childcare, healthcare, housing.” These are human rights. This is what a nation does. The United States is the richest nation in the world. It’s richer than it has ever been. If it means higher taxes, particularly on the wealthy, so be it. If they don’t like it, they can move to another country. Corporations have to pay their fair share. That’s not a complicated message.

Skarsgård: Do you think art and culture play a role in this? What can art do?

Reich: Art gives people a common language. It draws people into a community of common emotion and common insight. I first became aware of your work, Stellan, in Good Will Hunting, but I really remember River with Nicola Walker. That was such a powerful series. It gave me an insight, not only into your character but into culture, into the things we value and things that we don’t. The moral authority of a culture really depends on a fundamental agreement among people about what is right and what is wrong. And I think that what you do and what art does is it gives people those kinds of illustrations of public morality.

Skarsgård: Art should be automatically radical. Art is good at expressing the human condition, especially the parts you can’t express in words. It’s like science. You need science, even if you don’t know what you will use it for. Paintings, film, and music don’t need to be especially didactic or tell people what to think. But they should explore something new.

Reich: Great art gives you a sense that you are embedded in a culture, in a community.

Skarsgård: When I did theater, you could feel a moment on stage when suddenly the whole audience breathed at the same time. It was almost like their hearts were beating together. It’s a fantastic feeling.

in your life?

in your life?