In the winter of 2021, Arne Glimcher, the founder of Pace Gallery, told his son Marc that he had an idea for a show. The younger Glimcher—Pace’s CEO—replied that his father would have to wait three years for a slot in the calendar.

For the now 87-year-old Glimcher, who founded the original Pace in Boston in 1960 with $2,800, this was unacceptable. So he decided to open his own gallery, named after Pace’s first address: 125 Newbury. In the three years since it opened, the gallery has become an essential stop on the Tribeca circuit. Some of the works aren’t for sale; most of the artists aren’t represented by Pace, although the space exists under the mega gallery’s umbrella. A Kiki Smith show followed earlier this month, pairing her nightmarish paper mannequins from the 1990s with recent bronze birds.

CULTURED sat down with the indefatigable dealer for a conversation about where the appetite for risk that’s defined his career has led him.

CULTURED: It’s been about three years since 125 Newbury started. How did you develop the idea?

Arne Glimcher: It was very spontaneous. I’m a curator. I’ve always done these experimental shows that had a great deal to do with scholarship. One day I had this idea to do a show based on the line that artists tread between threat and seduction, like [Lee] Bontecou, [Lucas] Samaras, and Paul Thek. Marc [Glimcher, president and CEO of Pace Gallery and Arne’s son] said we could do it in New York in three years. I said to Marc, “I’ll just have to open my own gallery.”

I brought my team of four with me, and now we work at both galleries—being able to do things that don’t sell, that don’t have our artists in it. Everybody is so cooperative with 125 Newbury. They wouldn’t be so cooperative with Pace.

CULTURED: You signed a 10-year lease, right?

Glimcher: Optimistic, aren’t I? But I don’t feel old in any way. I don’t know if I feel any different than I did 25 years ago.

I called Marc and I said, “I have this space I want to rent. You want to come down and see it?” We took a little walk down Walker Street. “Dad, look at you. You’re a very elegant man. Is this where you belong?” I said, “Yes, this is where I belong now, starting again.” He shook his head, but he was also very proud of me because the gallery has shown very well on us.

I’m interested in what variations are possible at a time of such mannerism. Marc has said, in the 20th century we had our Renaissance, and now we’re in a period of mannerism. There’s some pretty good mannerists that come after the Renaissance, but for the most part, it’s a variation on art that art has already been made. I went to art school, and half of the galleries that I go to—we did all of that in art school. Where’s the connoisseurship? That’s the big thing now that I’m really upset about. It’s something that should be taught. Why is one painting by an artist much greater than the other 10 that artist has made? Other people may think I’m wrong, but I think I’m right.

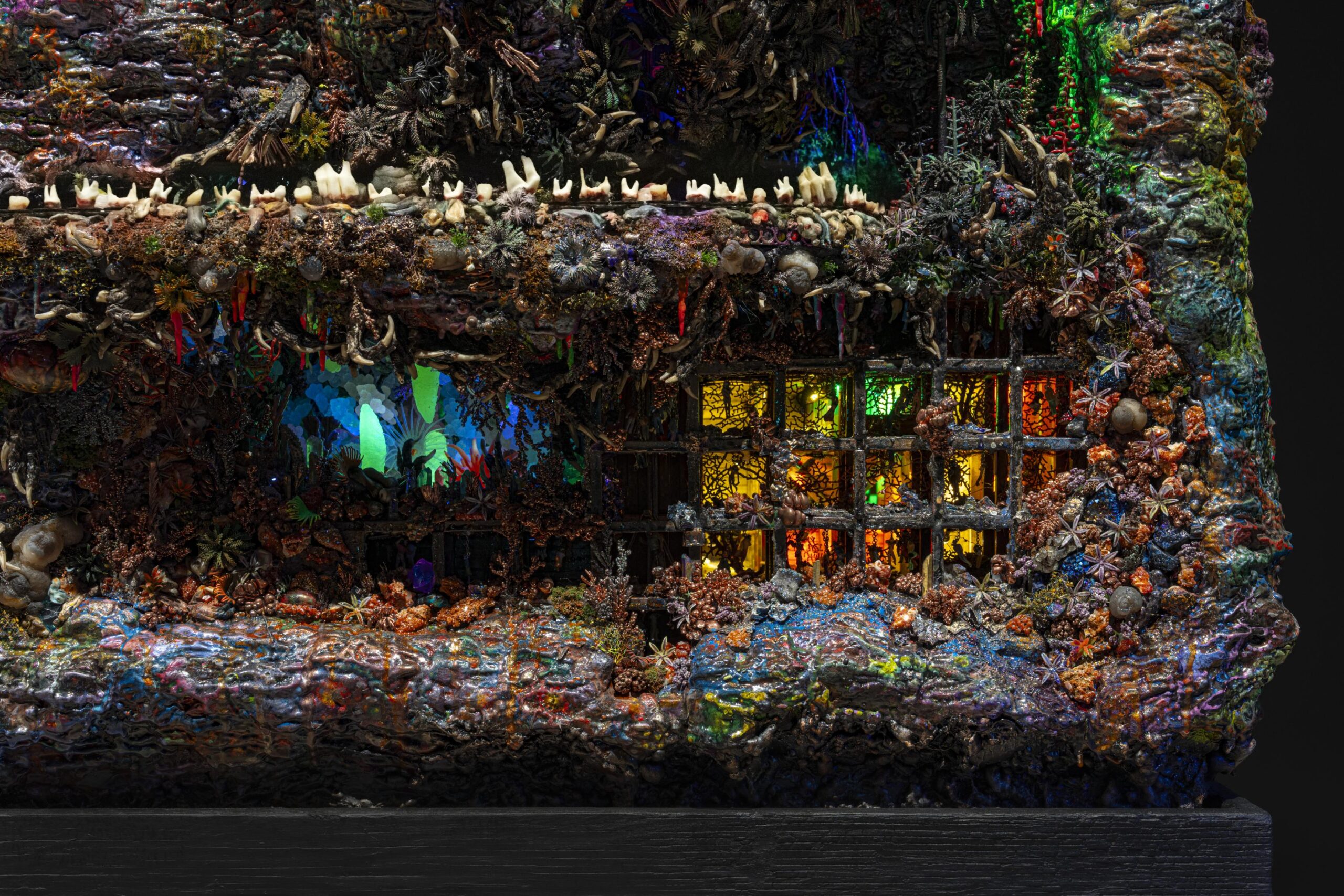

CULTURED: One of the things that I think has surprised and delighted people about the program is that it is this mix of artists who you’re associated with and known for working with for a long time, but also younger artists that maybe haven’t shown in New York, for example Max Hooper Schneider.

Glimcher: Max is a real original. I put a fortune into Max’s show. I built a pond. We cast all of those things. Max could never have done that if I hadn’t supported it. I’m thrilled that I can do that. That’s my role: to help make something original and wonderful happen.

CULTURED: Do you also have to make it pay for itself?

Glimcher: Frankly, 125 Newbury doesn’t pay for itself. I can’t get the audience down there, the people who would really pay the money. I’m very lucky that we’ve been financially successful, but it’s a miracle. Most of the younger dealers today, their friends are bankers. They live a very different kind of social life.

CULTURED: Do you think if you were starting out today in Boston that you would have the same success?

Glimcher: I don’t think you could start out today the way I did in Boston. I had $2,800. I had enough to keep it going for three or four months, and then it didn’t work. Very luckily, my older brother had some success in his work already, and he kept lending me money to keep the gallery going.

Even when we moved to New York, it was just hell. If you sold three or four things from the show, you were lucky. We didn’t have this much overhead. It wasn’t an international gallery. I could never have done that. That’s Marc. He’s on a plane all the time. But I did have that relationship with some artists. I had 30 years with Agnes Martin. I’d take calls in the middle of the night from her. She was having a terrible schizophrenic attack, and the next morning I got on a plane to New Mexico to take her to the hospital. We talked just about every day for 30 years.

CULTURED: Do you think it’s harder for artists now to build the careers they want without that kind of close relationship?

Glimcher: They weren’t building careers. They were making art. They didn’t give a damn about careerism or upsetting the entire art world.

CULTURED: How do you find younger artists now and decide who to invest in?

Glimcher: I was in Los Angeles, and I stopped at Blum & Poe on the way to the airport to say hi. And I asked Jeff Poe, “Have you seen anyone interesting lately?” And he said, “There’s this wacky artist that I think is really good.” He showed me pictures on his iPhone [of Lauren Quin’s work], and he said she lives nearby. I said, “Could you call her? Could I go to the studio?” On my way to the airport!

She had no idea who I was, but I came over and the studio was filled with paintings of such incredible vitality and passion that it knocked me out. It just hit me in the stomach. If I have a somatic response to art, that’s when I know it means something.

CULTURED: Who are some of the artists that you’ve had that response to recently?

Glimcher: I felt that way about Adam Pendleton. I think he’s a really revolutionary artist.

CULTURED: You’ve just opened an exhibition of KiKi Smith, with whom you’ve had a long relationship. How did it begin?

Glimcher: I knew Kiki from the time she was young. I represented Tony [Smith, Kiki’s father], and I remember when Kiki was Tony’s assistant. When he was dying, my partner at that time, Fred Mueller, and I were at the hospital sitting with him.

Kiki was always making things out of paper. This show is early paper works and new bronzes of birds. It is sensational. I thought it would be really interesting to play those two materials and times against each other.

When she was making these things, her sister was dying and all the work had a lot to do with death. Now she’s a married woman. She has stepchildren. Her life has changed so completely for the positive. So you’ll see these flying birds and these creepy characters that are like puppets.

CULTURED: In a letter marking Pace’s 65th anniversary in April, you talked about the fact that freedom to question and debate has been threatened. You said you believe in resisting censorship and embracing open conversation and believe that’s the role of a gallery. How do you think about the work you’re doing now in relation to that mission?

Glimcher: Right now, galleries and museums are being threatened. This Robert Longo show [“The Weight of Hope” on view at Pace’s 25th Street gallery in October] probably wouldn’t be taken by a museum today. It’s all about what Trump has done to our country. I think we have to fight it, and we have to make shows that are conspicuous, that get us in trouble. I was hoping for more trouble for this show than we got.

CULTURED: What kind of trouble?

Glimcher: I would like the agencies in the government to take note of what we are doing here. We have the First Amendment on the windows of this show.

CULTURED: I’ve been surprised by the fact that many museums have fallen into a defensive crouch in a way that certainly didn’t happen during the first Trump administration.

Glimcher: I have a lot of problems with museums today, and that’s part of it. How much money is the government in Washington giving to museums in New York? Nothing. Why not be bold? But they’re afraid.

CULTURED: Some are worried about losing their tax-exempt status.

Glimcher: Yes, but I believe strongly in equality, and I fight with my life for it. It’s just ridiculous the way museums have decided that they have to be politically correct. Installations in museums where things from different periods are mixed. Even at the Met, when you come across a modern thing in the African tribal galleries—I’m not interested in that.

CULTURED: Is that political correctness, or is it trying to engage a different or younger audience?

Glimcher: But how great is the accomplishment of those African sculptures themselves? Who needs something that’s au courant to make you see the other artist in a different way? I want to see a room of paintings from the Renaissance. I want to understand that period of time. I don’t suddenly want to be in a room of Renaissance paintings and see a Brice Marden.

CULTURED: I think it’s different when you’re trying to build an audience that feels more comfortable with contemporary language, and that serves as an access point. With museums, the deck is stacked against them in terms of getting people in the door.

Glimcher: Go to the Met on the weekend. It’s packed. Museums are now a date place. It was a very different thing when I started out. Museums didn’t have so many curators. Alfred Barr [the former director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York] and Dorothy Miller [a MoMA curator] would come to Pace. She’d pick things out: We’ll buy that and we’ll buy that and we’ll buy that. Now, there are 10 curators who have to sit on a committee with trustees. What you get is a fantastic collection of mediocrity because the decisions are being made by committee.

CULTURED: What have you done in a situation where an artist has shown you work that you think is really not good?

Glimcher: It’s not my role to say it’s not good. If I believe in this artist, I show it.

CULTURED: You’ve been very modest about your role as a businessperson, but you did build this into a big mega-gallery. How did you start your international expansion?

Glimcher: I started with China. The expansion to other countries was with Marc.

CULTURED: China is having an interesting moment now because Pace’s Beijing location has closed, and Hong Kong is closing, right?

Glimcher: You couldn’t do business there. Boy, Beijing was great from 2008 to maybe 2015. We did a lot of business. I loved China and had so much fun. But one reason is we didn’t like the space [in Hong Kong]. We can’t show large things in it. And the overhead is like New York. We’re selling to our Asian collectors from here or at the art fairs.

CULTURED: But the artists still want to show there?

Glimcher: The artists do want to show there, but I think they wanna show more here. I’d rather we open in Paris. We thought that London was better than Paris, but that was before Brexit. Then everybody moved out of London.

CULTURED: Do you think you will open in Paris?

Glimcher: We’re looking now.

CULTURED: How do you balance the historical work and the contemporary work at 125 Newbury?

Glimcher: I’m not trying to have a balanced program. I’m trying to make the exhibitions I want to see. If people don’t like the shows, it’s too bad.

CULTURED: How do you cultivate drive and curiosity? If you wanted, at this point, you could just relax on the beach and read.

Glimcher: It’s not what I want to do. For the most part, I’ve never been able to go away for more than a couple weeks. It drives me crazy. Even when I’m doing that, I’m writing. I’m just finishing my memoirs.

CULTURED: How long has that been in the works?

Glimcher: About six years, and I’m now cutting it back from 1,000 pages with no pictures to 625.

CULTURED: What was the process of writing that like?

Glimcher: I can conjure the past and be completely absorbed in it. And at the end of the day, it’s a fabulous ride but also a fabulous fall because nothing is like the times that I lived in. Sometimes I’d be so happy writing and then that evening I’d get so depressed. Sometimes I stopped for two, three weeks and couldn’t write, but then I’d get myself back.

CULTURED: Is there anything you were nervous about sharing or revisiting?

Glimcher: I think some people will be unhappy. But I’m not a mean person, and I haven’t had a nasty life. It’s been challenging, but it’s been a marvelous life.

in your life?

in your life?