Life as an underground comic book artist in the 1970s was as freewheeling as you imagine—just ask Robert Crumb and George DiCaprio. The two men, now in their 80s, had the kind of meet-cute that only old-world New York could conjure: DiCaprio offered his illegally inhabited loft to Crumb’s crew.

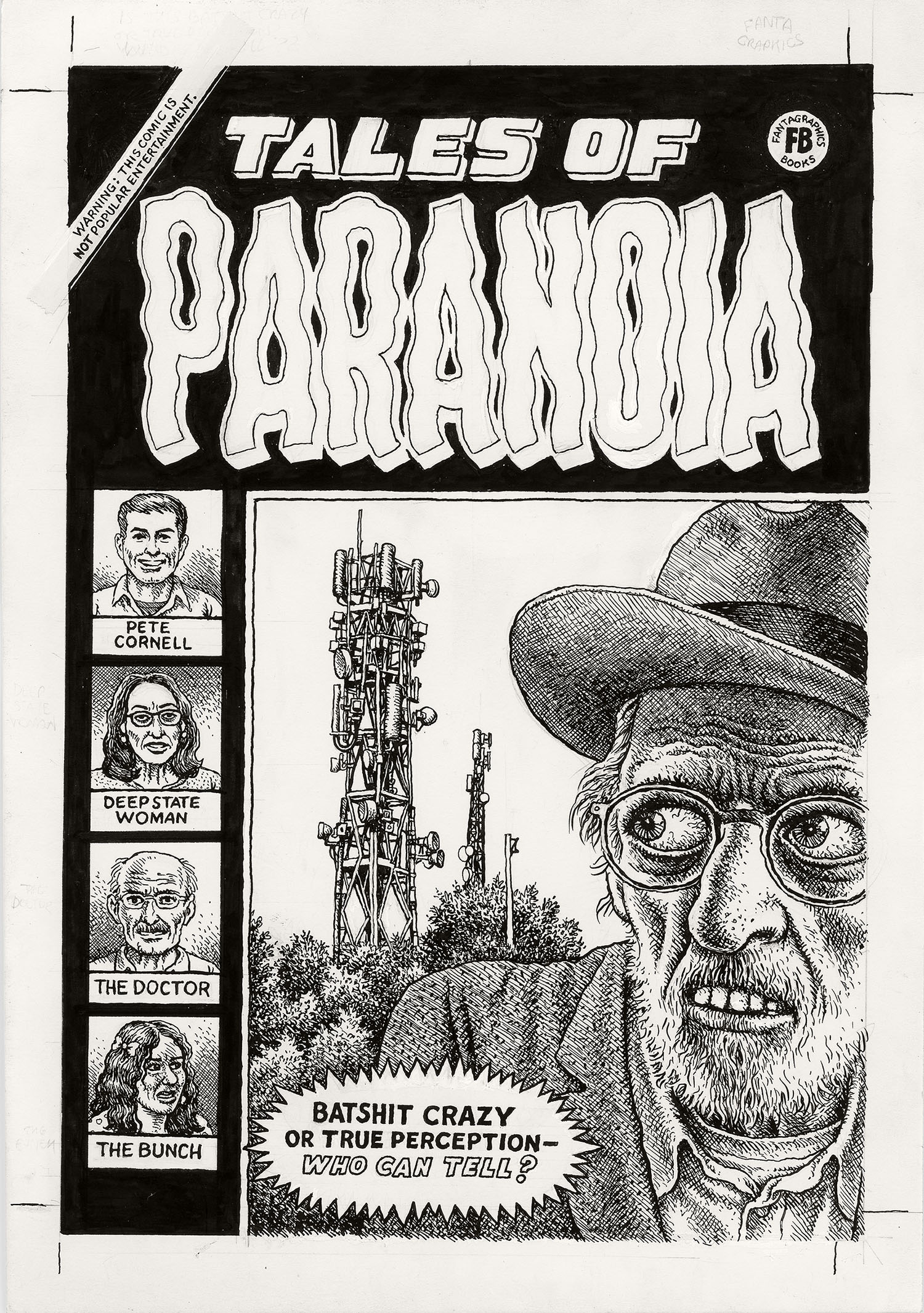

The encounter was fortuitous. Crumb got DiCaprio the animation job that led him out West, where he ended up working as a comic book distributor and became the father of celebrated actor Leonardo DiCaprio. Meanwhile, Crumb emerged as one of the leading satirists of American culture. In November, he released Tales of Paranoia, his first solo comic in 23 years, published by Fantagraphics. Coinciding with an exhibition of new drawings and prints at David Zwirner in Los Angeles, on view through Jan. 10, the book explores personal and mass paranoia—particularly surrounding illness and disease.

To revisit the bad trip that inspired Crumb’s new book, the creative scene that formed them, and the future of their art form, the two friends connected with cartoonist Sammy Harkham—a member of a younger generation shaped by their work—for a sprawling Artists on Artists conversation. Conspiracy theory, autoerotic asphyxiation, escaping jail astrally—nothing was off the table.

Sammy Harkham: How did you two meet?

George DiCaprio: Bill Skurski, an East Coast underground comics guy, told me you were in town, and I said, “I have this loft that can put up the Cheap Suit Serenaders.”

Robert Crumb: We were always looking for some place to mooch, and we had no money.

DiCaprio: This was an illegal loft, which meant you couldn’t sleep there at night. There was an elevator in the middle, and supposedly, the fire department would ride up and look around to see if anyone was living there. All we had to do was find places to sleep that they couldn’t see.

Harkham: And then you came to LA?

DiCaprio: I came in ’73. Luckily, Robert did me the big favor of mentioning my name to [American animator and filmmaker] Ralph Bakshi, who was putting together a movie called Heavy Traffic.

Harkham: What was the job?

DiCaprio: I was an animation assistant, which was almost like slave labor back then. You had to punch the holes in the vinyl, and it all had to be perfect—otherwise, it didn’t line up. I remember staying in that studio for four or five days at a time and just sleeping on the floor.

Crumb: There was very little financial reward in comics in those days. You had to do it for the love of it. A lot of people would dabble in it and say, “What’s the point? Hardly anybody reads it. It’s a lot of work.”

Harkham: It’s still the same.

Crumb: Well, that kind of keeps the comic business pure because the bullshitters that go for the money and success and fame take one look, and think, Eh, not here.

Harkham: What are your current obsessions?

Crumb: I’m conspiracy-obsessed. I probably shouldn’t say that publicly.

Harkham: You’ve been interested in paranoia and conspiracies for a long time. What sparked you to actually put it on paper in Tales of Paranoia?

Crumb: It took me a long time to figure out how to do that in a comic. Comics are all about action; conspiracy is very abstract. My worst fear was that it would just be me talking, panel after panel, which is not everybody’s favorite thing.

Harkham: George, what about your big inspirations these days? What do you collect?

DiCaprio: Underground art. I have one especially incredible piece: a letter by [cartoonist] Vaughn Bode to Leonardo [DiCaprio] before he was born, about how wonderful his life was going to be. Poor Vaughn passed away two weeks after he wrote it. I keep the letter because people say he committed suicide. The letter to unborn Leonardo is not the kind of letter written by someone who has suicide on his mind. It’s an artifact that I cherish.

Harkham: What was the official cause of death?

Crumb: Well, I heard that he was sexually kind of odd. He was doing one of those strangulation things.

DiCaprio: Autoerotic asphyxiation. It was an accident, I’m convinced of it.

Harkham: Recent books like Flamed Out: The Underground Adventures and Comix Genius of Willy Murphy help me realize that even through that era that has been so romanticized by cartoonists of my time, it was actually a horrible, awful existence.

Crumb: People had a good time, though. A lot of dope smoking and a lot of fucking going on. And you could scrape by in those days. Rents were cheaper.

Harkham: At that time, comics were permeating the culture. Now it’s a lot more difficult.

Crumb: Did I hear you say permeate? No, comics didn’t permeate the culture. It stayed on the fringe. It was never mainstream.

Harkham: I guess I’m thinking about stuff like East Village Other, and those free papers—how it just seemed to be all over because of the press syndicate.

Crumb: It was strictly in the hippie youth culture. The rest of America knew nothing about it.

Harkham: George, you and Robert lived in San Francisco and worked for [San Francisco underground comic publisher] Ron Turner.

DiCaprio: We did a comic book with [American psychologist and psychedelics advocate] Timothy Leary called Neurocomics. He had written a book called Neuropolitics, which was so complicated. Neurocomics was an attempt to simplify some of the very good ideas in there. I know that you have a different opinion of him.

Crumb: I admired Leary when I was taking LSD, then I made fun of him in a comic, and he was very angry. He cursed me out in print. He said I was one of the most dangerous people in America, and I’m proud of it.

DiCaprio: He once claimed that if we were able to inhabit outer space in a no-gravity situation, our evolution would speed up geometrically. That’s an interesting theory.

Crumb: That’s around the time when I thought he was getting kind of unhinged. We’re a long way from overcoming the gravity issue. Long-term, being in space is not good for the body. The other way to overcome gravity is astral travel.

Harkham: You have studied that?

Crumb: I’ve studied the out-of-body thing and experienced it. It’s not that hard, but it was too time-consuming to practice. I wasn’t especially gifted at it.

Harkham: George, have you ever dabbled in that?

DiCaprio: There’s an interesting cousin to astral projection.

Crumb: Remote viewing? I studied that too.

DiCaprio: Then right after that, acid came along—another form of astral travel.

Crumb: The thing about LSD is that you’re a complete amateur when you’re 22 years old. You take this drug, and suddenly you’re in a world that’s basically made for professionals to travel in.

DiCaprio: Leonardo did a movie called Inception that deals with dream states and stuff like that. After that, people started sending me material about how to induce a dream where you’re flying. I started gathering information about it, and suddenly, a lot of people were writing me as if I knew a lot about it. Then, I discovered that everyone who was writing to me was in jail. I had to leave that chat room.

Crumb: Huh, that’s interesting. A couple of people that I was corresponding with in prison were writing to me about how to escape physically, not astrally.

Harkham: George, when did you first discover Robert’s work?

DiCaprio: It was a big book called Head Comix that my friend showed me. It wasn’t a comic book. Then, you surprised me by recommending me for that job. Inadvertently, you were an agent of change.

Crumb: Well, I’m not sure getting involved with Ralph Bakshi did you any favors.

Harkham: But that turned out to be a great job in terms of what it taught you as an artist.

Crumb: In those days, you’d learn by mistakes, a lot of them. When I saw the first printing by Rip Off Press of Big Ass Comics, I thought, Oh no, what a mess, oh my God. It’s a lot to figure out. That to me is still my favorite format—the simple comic book—what they now call a pamphlet.

Harkham: Final question. What can art do?

DiCaprio: Wow. What can art do?

Crumb: It can express, entertain, confuse, disturb. And it can fill a space behind your couch.

You can purchase a copy of the Artists on Artists issue, featuring this conversation and many more, here.

in your life?

in your life?