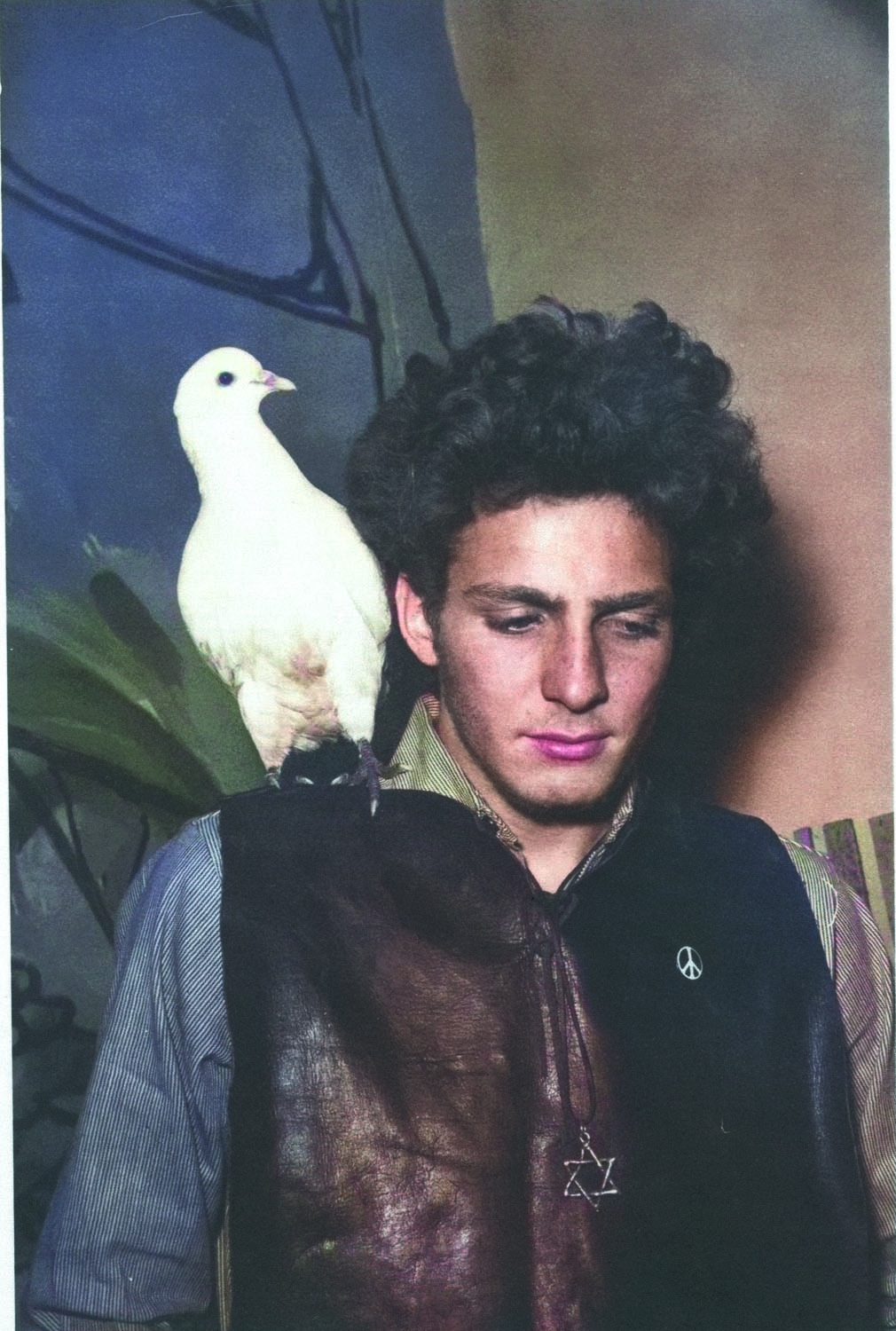

Before the jewelry empire, before the house in Amagansett, before David Yurman was ever a household name—there were two young artists living in New York. David was working under sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, and Sybil was a ceramicist and painter who had been taken under Sho ̄ji Hamada’s wing. On their first date, David showed Sybil how to create patinas on metal, and the first piece of jewelry they worked on together was for Sybil to wear wherever she went. The couple, now in their 80s, have spent over 50 years together, making artwork and jewelry through the decades. It would be a cliché to say that they finish each other’s sentences, if it weren’t also true.

In the 1970s, as the Yurmans’ wearable works caught on among the downtown art set, Sybil—who had been keeping the business afloat by selling her paintings—came in-house, contributing the sharp eye that gave the David Yurman jewelry line its unique identity. These weren’t pieces for a man to buy a woman. These were pieces a woman could choose for herself. Though David and Sybil passed day-to-day management of the now-behemoth business off to their son in 2021, the couple is as busy as ever.

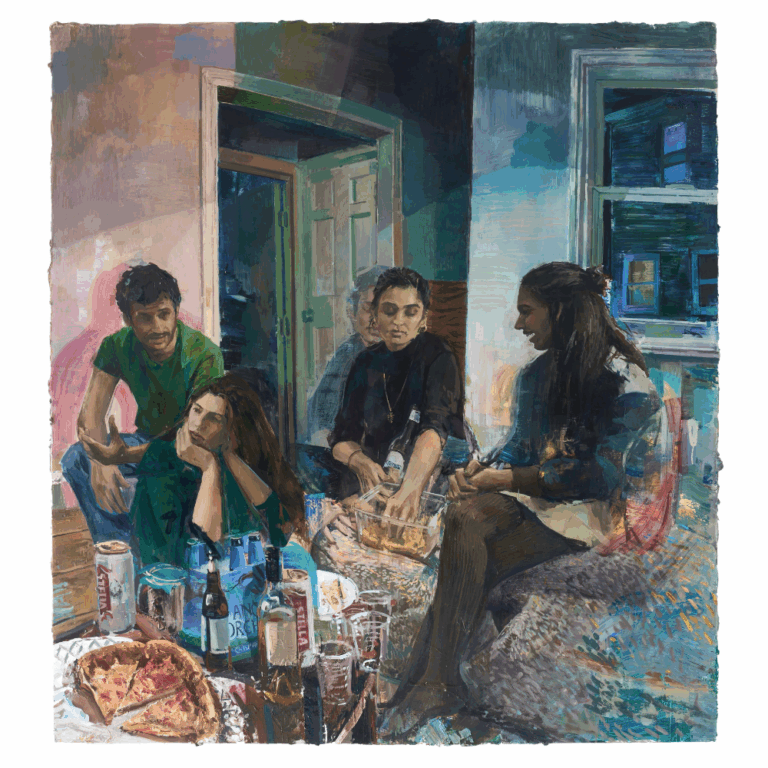

Their personal archive—a treasure trove of paintings, sculptures, photos, and, of course, jewelry—is the subject of an extensive tome, Sybil and David Yurman: Artists and Jewelers, published last month. CULTURED sat down with the couple to reflect on where it all started.

Sybil Yurman: Once I was given the key to Austin.

David Yurman: I think it was San Antonio.

Sybil: At the ceremony, Madeleine Albright, Hillary Clinton, and all these formidable women spoke before me. I was–

David: Intimidated.

Sybil: They even brought in a strategy person to rehearse me, and usually I never need any rehearsing. Probably 1,000 women came to this luncheon to hear me speak. I looked at them and said, “I realize you’re only interested because I’m David Yurman’s wife, but let me assure you, I existed before I ever met him.” Which is a long way of saying I was a person before I met David. I was a ceramicist at Berkeley. I worked in Raku pottery with Shōji Hamada at the Corcoran in Washington, DC.

David: It’s like if you said, “You know that guy Picasso? I was working with him in the South of France for about five months.”

Sybil: I didn’t graduate from high school. At a very early age, I played hooky from school, went to the Museum of Modern Art, saw the Monet paintings of the water lilies and said, “I just have to paint the feeling of what I see. I don’t have to know how to paint.” I started to make paintings and sell them, and I used the money to run away from home at 16.

David: Where did you run to?

Sybil: San Francisco. I lived in a place called the Hyphen House, where a lot of writers lived. Lou Welch and Michael McClure…

David: When he wasn’t drunk, you’d see Kerouac there.

Sybil: In the daytime he wasn’t drunk, but he didn’t wake up ’til late in the day. I met David when I was starting to make jewelry. I got a job working for a group of sculptors, and David was one of them. I was told that he worked for Jacques Lipchitz, the Cubist sculptor, on the restoration of his African art collections, so he knew a lot about patinas, the finishing of metals. I wanted to do more of that with my jewelry. I asked him, “Could I come over and see your patinas?”

David: The best line ever.

Sybil: I thought you liked me. You kept bringing me coffee in the morning, and I don’t even drink coffee. That was the first sense of betrayal: I drank the coffee.

David: Our relationship started with a sense of betrayal. [Laughs] I grew up in Long Island. I was always going to the Village during school to listen to poetry and music. I was a terrible student, barely graduated, but I was a dancer and an athlete. I actually danced in the girls’ modern dance club. I was the only male dancing. What I couldn’t do is what got me to do what I could do. You move towards recognition and praise and things that fill you up. I had none of that at home. I had a very distant and sometimes cruel relationship with my family.

My father lost his belt and trimming business and became a salesman for a friend of his in lumber. In 10th grade, I went to Eugene, Oregon, for two months. They had never seen a Jewish person. They didn’t know why I didn’t have horns. Then I realized that I was free to go anywhere. So when I was 16, I traveled to Provincetown, where my sister was a waitress, and was dating a very interesting sculptor who was making welded bronze sculptures. He taught me how to make fire and move metal.

Artists either have a natural inclination or they don’t. You really can’t teach this—although I shouldn’t say that because schools make lots of money doing it. It’s really the ability to play. I had to play, because anything else was torture. Even when I work with my design assistants for the last 40 years, I play with them. I was always worried about making a living, so I made direct-welded sculptures and turned them into necklaces and bracelets mostly. I learned how to sell, which I liked because it was a connection to people.

When I first saw Sybil’s work, it was something she called “Sky Markings.” They were very airy, totally unforced. I was really attracted to them. I probably told you this, but I may have liked your paintings more than I liked you. The first two years, when we decided to do the jewelry business together, I couldn’t ship a box to the right address. Sybil was organized. She put thousands of dollars into the company to keep it afloat. I still owe her at least $60,000. I think it came out in the wash.

Sybil: I liked David’s work very much. He made these beautiful angels and figures. They were very lyrical. When we started dating, I asked him if he would make me something in his style that I could wear. That started this whole other world of ours.

We went into a gallery, and the woman asked me where I got the piece that I had on. I said, “David made it.” She asked, “Could you make more?” I said yes. He said no. I left the piece with her to show some customers. That’s what started this whole other world of ours. By the time we got home, she had sold four. He said, “Now what? Am I going to sit here and make these?”

David: I made them in the maid’s room in Sybil’s apartment.

Sybil: It’s always been a language between us. Once, we were going on a date. I came down to his loft on Delancey to get dressed, but forgot my belt. He said, “I’ll weld you one.”

David: I have no sense of time management. I thought I could get it done in about a half hour.

Sybil: It took closer to three. I fell asleep, and when I woke up, he gave me this great belt. We never made it to the party.

David: Most of the concepts came from me and were edited by Sybil. She could come in and look and say: “It’s too thin,” or “I would never wear that,” or “I think you did that one last year.”

Sybil: When we first started, women didn’t buy jewelry for themselves. It was only a gift. Can you imagine? Even 50 years ago. A woman would usually be getting her money from her husband, so if she bought herself something it couldn’t be too expensive. Part of our objective was to allow women to express what they wanted, rather than getting that one little ring with a stone in it that didn’t express anything except someone’s affection for them. You asked why I went from art to jewelry. I felt that I could express myself within this other venue.

David: We’re living creators that do art and jewelry. We’re husband and wife, like–

Sybil: Ray and Charles Eames.

David: I thought Ray was the brother for years. I didn’t know that was his wife. Not that he was chopped liver, but she really was the powerhouse that kept their operation moving. I don’t know if Sybil is or I am. Some days I am, some days Sybil is. We’re a good balance.

Sybil: The biggest thing is that we’re both able to receive criticism. There’s a real feeling of self-assuredness and a stability that allows us to collaborate. We don’t have to compromise.

David: No, you don’t compromise at all. [Laughs]

Sybil: Forget compromise. It’s not a good word because it’s not what you really want to do. You really want to collaborate. You want to hear the other person. It’s like dancing. We like to dance. We’ve been together for 57 years, so we’ve learned to work through all the bickering.

David: Our other saying is…

Sybil: “It’s better to be kind than right.”

David: These sayings come out of the things that we have the most difficulty doing.

You can purchase a copy of the Artists on Artists issue, featuring this conversation and many more, here.

in your life?

in your life?