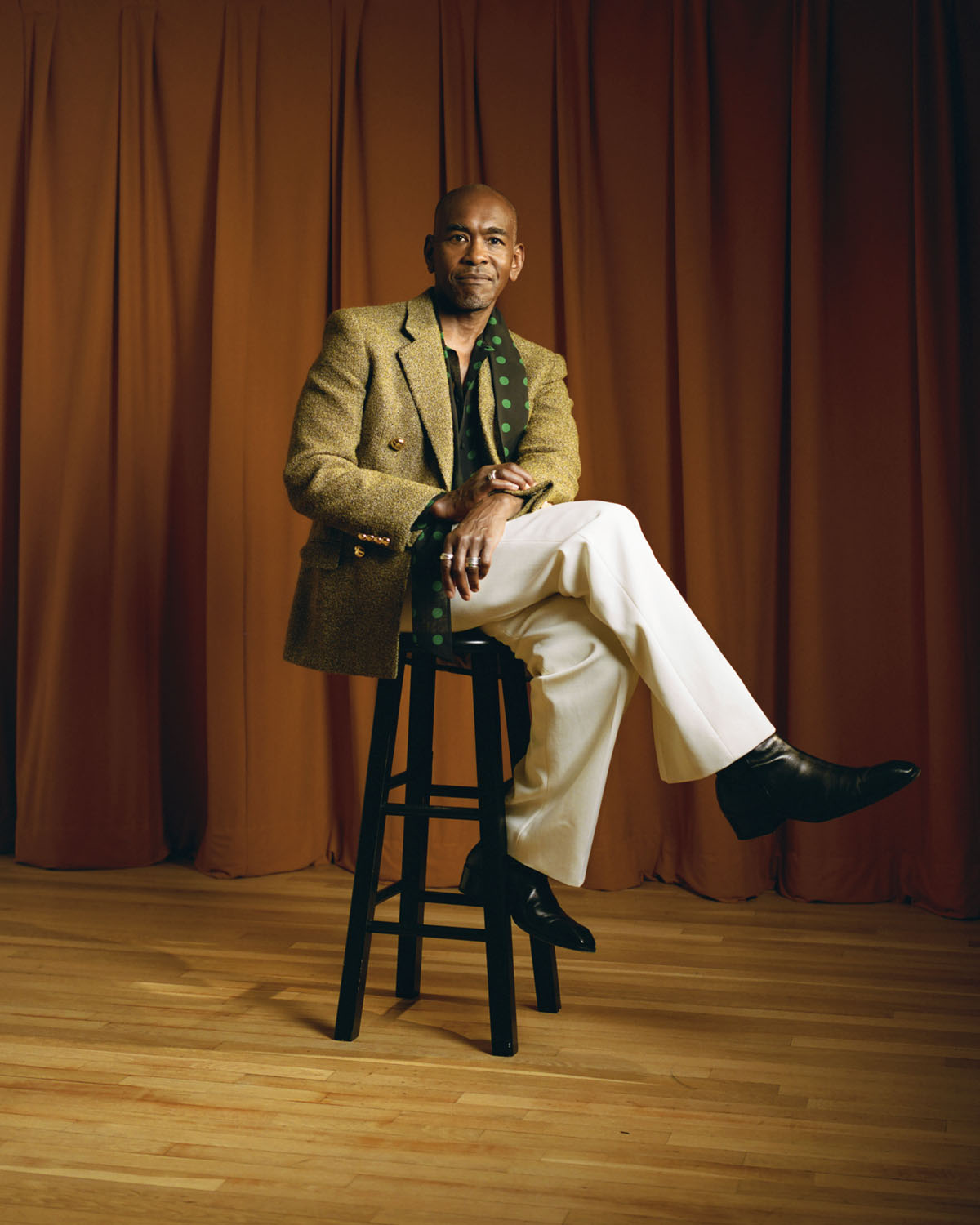

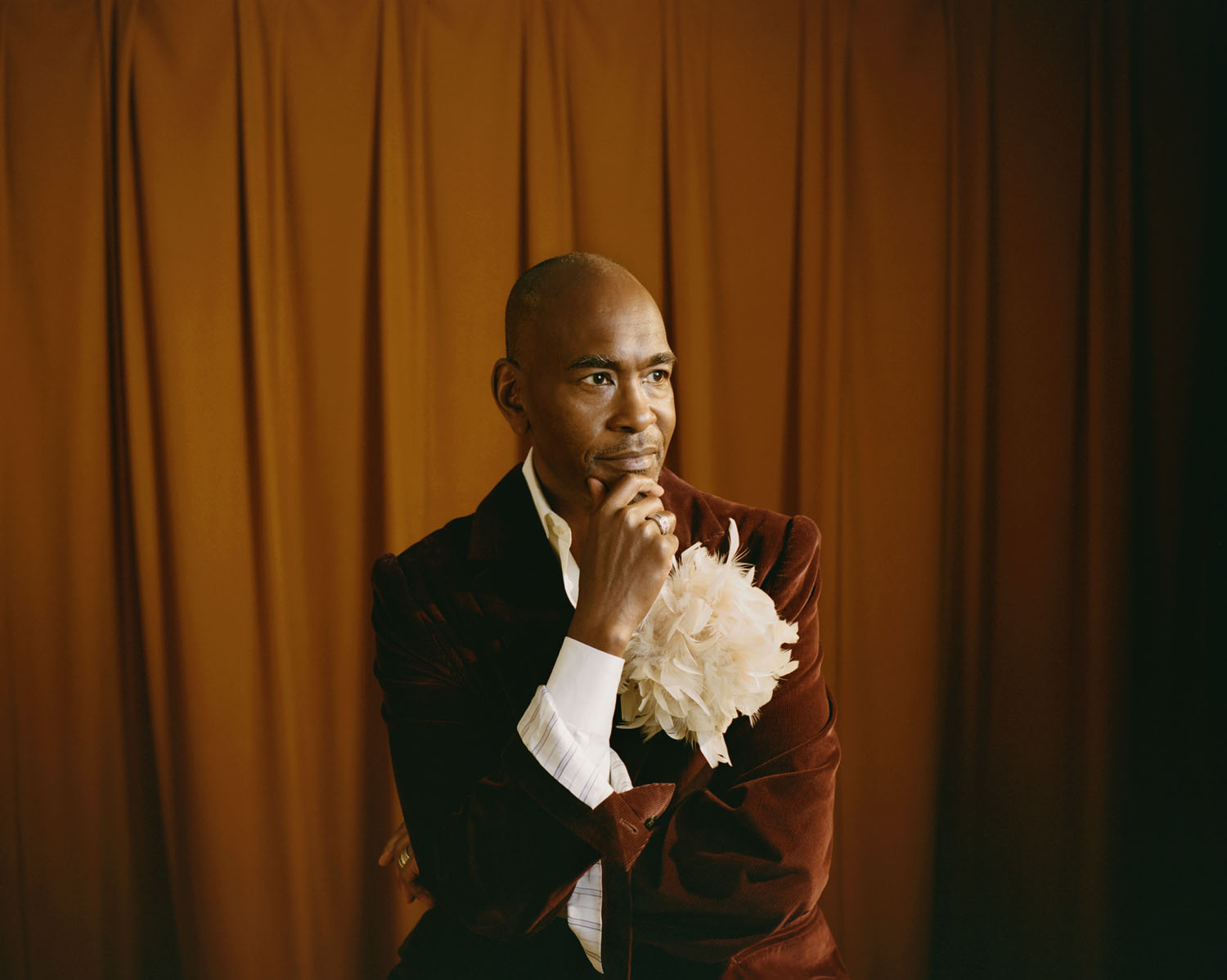

“This is everything,” Paul Tazewell told the audience as he held his Oscar aloft at Los Angeles’s Dolby Theatre earlier this year. In the crowd, the muses he has dressed, from Ariana Grande to Rachel Zegler, rose to give him a standing ovation. That night, the Akron, Ohio, native became the first Black man to win the award for Best Costume Design for his work on Wicked.

Voluminous tailoring aside, Tazewell’s trademark is his collaborative bent—bringing silver screen A-listers and aspiring theater actors alike into the dressing room for long and winding conversations about character direction. “How do you see this role?” and “What are your intentions?” are just two of the queries that have yielded some of this century’s most indelible costumes. There was his Lin-Manuel Miranda one-two punch with 2008’s In the Heights and the culture-shifting 2015 run of Hamilton. A turn at the Metropolitan Opera with Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, based on the memoir of former New York Times op-ed columnist Charles M. Blow. And of course the worldwide phenomenon that is the Wicked franchise. Two short months after his Academy Award win, Tazewell stepped out at the Met Gala to showcase his collaboration with Thom Browne for carpet mainstay Janelle Monáe. “This collaboration is just the beginning,” he noted. “More to come.”

It was on the set of 2019’s Harriet, where she starred as abolitionist Harriet Tubman, that the designer first met his now-frequent co-conspirator, Cynthia Erivo, who chronicles her life onscreen in her new memoir Simply More. They found themselves side by side again when Erivo was cast as the all-green Witch of the West, Elphaba, in 2024’s Wicked. Before they reunited for the release of Wicked: For Good, the pair sat down to discuss how what happens in the dressing room—existential questions, scrapped ideas, and reality checks—lays the foundation for everything we see on screen and stage.

Cynthia Erivo: The first time I met you was in a little studio.

Paul Tazewell: We were in that weird, political building they had put us in.

Erivo: I remember you had so much around you: sketches, fabrics, tulles, everything. Wonderland. And this little space where we would take photos. We were just getting to know each other. It was fast, wasn’t it?

Tazewell: There was a bond that happened. You gingerly walk into it because you’re trying to figure each other out, but then you find a safe space with each other, which happened very easily with you.

Erivo: I remember the first time I saw the sketches—I think it was Harriet’s green dress—that was [like], Oh, you see her how I see her. For a long time, we only had one well-known image of Harriet, quite serious and staunch. But you researched and found that picture of her in that beautiful gown. That’s how I had seen her in my head. That [famous] picture is so far away from the beginning of her story.

Tazewell: Those designs were some of my favorites, because it gave me the opportunity to represent her depth and grief. You said to me that you saw her in the same way that I did: a woman who has gone through the journey of being all parts of a woman. With everything that we’ve done together, I expect that you’re going to invite that kind of journey.

Erivo: You asked me, “What do we want her coat to look like?” I remember thinking, I have a say in this. That’s really cool.

Tazewell: Remember the photo shoot that we did at the very end? There’s one [photo] where you’re in that caped coat—the blue one when she becomes an officer—and it was one of my favorite photos of the two of us. I was adjusting something on the coat, but it was just such a wonderful moment.

Erivo: We have to make sure we get those pictures whenever we can, so that we spot those moments, because I feel like we’re going to be doing this for a while, you and me. When you start figuring out what each character needs for their story, at what point does the sketch happen?

Tazewell: I’ve got to find myself in the story—with Wicked and even with Harriet. When I found that photograph of Harriet, I said, “I can see the depth of who this woman is and I can identify with her. Therefore, I can dress her.” With Elphaba, it was the same. I was listening to the music over and over again. I started to identify with her, with the story, because it made direct sense with my own journey as a Black man, feeling marginalized, all those things. When Jon [M. Chu, the director] mentioned he was speaking to you, I thought, That’s perfect. Why hasn’t this been done before?

I designed the wardrobe [for] Elphaba first, and then the rest of the world defined itself according to who she is. As people are cast, I’m adding in the DNA of those actors—of you and Ari [Grande] and Jeff [Goldblum]. The way that I work is always going to be defined by who’s playing the role. You have to find the reality within the fantasy, because we’re going on this journey and we need to believe it for that moment in time.

Erivo: It has to match both the character and the actor’s DNA.

“I can see the depth of who this woman is and I can identify with her. Therefore, I can dress who she is.” —Paul Tazewell

Tazewell: I get into a fitting and I ask a lot of questions: How do you see yourself as this character, what are your intentions, and how I can bring that out? There’s a beauty in working with you because you are able to articulate where you are with the character.

Erivo: Did you always want to put Elphaba in trousers or did that come along when I was cast?

Tazewell: You were already cast. It was a push to imagine, If she is in control of her evolution, what would she do? All the work that we did with Harriet—I’ll always go back to you running through the field in the grass. It was that kind of athleticism, tenacity, energy that you bring to playing a character, and the commitment to bringing forward that story. It inspired me to open up the possibility of how we can reshape who she is.

Erivo: Is there a different process for working on a play or a musical than a film?

Tazewell: The muscles are the same. I’m always thinking about character and the most compelling way to tell the story. With stage, it is easier to be an abstraction. There’s a suspension of disbelief, and you buy into it. With film, you’re going to have people in real spaces. The costume has to then follow that. And the scheduling—especially for two films shot at the same time—is a nightmare. We had to figure out your whole story before starting to shoot. Except for that last book, which we didn’t talk about. That was perfect, because we were able to spend so much time manifesting who she was together, and then we just knew who she was.

Erivo: I don’t know that many people would be able to roll with the punches in that way. You move through the journey of these characters, these people, the piece, and as you’re learning them and growing with them, you discover a thing that this person might need. I would bring that to you and you would just accept it and say, “That is a good point. What do we do?” How do you make the time to make something completely new in the middle of making what’s there?

Tazewell: You live in the world of “yes.” That’s how I choose to design, especially for Wicked. My priority was to make it as right as possible. You said once, “I think we want to investigate this.” It was important to investigate, and then it failed. If I start to say, “Oh no, we can’t do this,” it sets up a different kind of dynamic that isn’t creative.

Erivo: What I love about your process, because I’ve heard you talk about it before, is the way you draw from the world around you so that everything is still technically connected to what’s outside of us, as well as being a part of what we are on the inside.

Tazewell: I’m a huge analog researcher. I love going through books and being inspired by photographs and paintings. I put all that in the pot and then I pull out of that where appropriate. A lot of it is visceral: I would look at you during a fitting, mock something up, and know that it was the right thing.

Erivo: When did you know that this is what you wanted to do?

Tazewell: When I was in college in North Carolina, we had Ann Roth as a guest teacher. She mentioned that I should pursue costuming.

Erivo: Ann Roth, as in Ann Roth, Ann Roth?

Tazewell: Yes, she was doing Places in the Heart. That was the movie with Sally Field, set in the ’30s on a farm. She mentioned to me that there are very few people that are really studying streetwear and applying that to design. It was a blessing, but then as I evolved—because my love was research and work and classics, the door opened towards those pieces that were very specific to Black culture—it felt limiting.

When I was 16 years old, I designed and performed in a production of The Wiz in high school. I made the choice to step behind the actors, but I also have the spirit of an actor. I realized that I [could] step into the shoes of any character and design for them. I just don’t get to do the performance.

Erivo: You can put yourself in the shoes of the character, but also, once that has been done, you are able to step back and allow whoever is playing the character to influence the work from their end.

Tazewell: A costume on a rack is a dead costume. It only comes to life once you step in and breathe life into it. That is the extra part of design: having the foresight of how you’re gonna move in the costume, and then that becomes part of the design overall. That’s what I love; that’s my joy.

Erivo: If you could design for any director, who would it be?

Tazewell: Gosh. [Guillermo] del Toro.

“I have the spirit of an actor. I just don’t get to do the performance.” —Paul Tazewell

Erivo: Is there a piece of cinema that exists that you wish you could have designed for?

Tazewell: Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. Also, The Leopard, Death in Venice, and A Room with a View, which have amazing designs.

Erivo: I have one last question for you, Paul. What can art do?

Tazewell: Having experienced what we both did… it was everything. It was you, it was Ari, it was Jon, it was all the rest of the cast, everyone it took to make that happen. I hope that it will be epic in some way, and that it will be a really meaningful story that will touch hearts. That’s why I do this: to tell stories as clearly as possible so that people can take something away and make the world better. I don’t know what the next one will be yet, but I’m waiting. And I hope you write it!

Erivo: That really is the heart of it, isn’t it? It’s why we do what we do—we are trying to communicate with the world that surrounds us and simultaneously make it a better place. Both of us are quite lucky that we get to do it together often. And hopefully we will keep doing it often, if you’ll have me.

Tazewell: Anytime.

You can purchase a copy of the Artists on Artists issue, featuring this conversation and many more, here.

Grooming by Leanna McAlpin

Lighting Tech by Mark Jayson Quines

Production by Dionne Cochrane

Photography Assistance by Yashaddai Owens

Styling Assistance by Alana Powell

Grooming Assistance by Emily Disanti

Production Assistance by Brittany Thompson and Thalia Saint-Lôt

in your life?

in your life?