Jen Tullock is quick to throw out a book recommendation for Donna Tartt and then philosophize on why she enjoys books written by misogynists: they tell her something about herself. And besides, the actor’s latest role is a problematic author with a penchant for bending the truth. So call it character research.

Tullock—who plays Devon Scout-Hale, arguably the most normal character in hit thriller series Severance—has ricocheted to the other end of the spectrum playing 12 tumultuous characters in a one-woman play that she co-authored, Nothing Can Take You From the Hand of God. Running through Nov. 16 at the Peter Jay Sharp Theater, the show centers on a best-selling writer whose book about growing up queer in the evangelical South is plagued by accusations of made-up affairs. The production is loosely inspired by Tullock’s own upbringing in the South, and bolstered by her overflowing personal bookshelf, which includes lots of Melissa Broder alongside weathered copies of Lolita and Jonathan Franzen. “That is part of reading,” argues the actor.

As Tullock winds down the run of her play, she sat down with CULTURED pre-curtain call for a closer look at the inspirations behind the two-time extended show. If you disagree with her taste, well, Tullock is more than ready to defend her choices.

How did your experiences weave their way into Nothing Can Take You From the Hand of God?

The impetus for writing the play was my own frustrated response to how tired and stale I find so many queer-in-the-church narratives to be. In the zeitgeist, we often canonize queer people to the point that we end up othering them further and further. The play itself is fiction. There’s certainly safety in the distance of that fiction, but it is loosely inspired by my upbringing in the evangelical South by missionary parents, and having gone to an evangelical school that was unofficially affiliated with a mega church, and all of the cuckoo doctrine one might expect. I realized as a young teen that I was gay and that wouldn’t work within those confines. I hadn’t seen—either in film or in literature—stories of the abuses gay people had suffered at the hands of the evangelical church where the story didn’t typically end there.

So, I wanted to look at how hurt people hurt people and what happens when someone who has suffered greatly also metabolizes that suffering into their own manipulative tactics. It is about a writer named Frances, whom we meet at the beginning of the book tour for her second book. This book details a lot of her upbringing, but it also tells several other folks’ stories that are not necessarily hers to tell. When she receives a cease and desist order, she has to go home to Kentucky to try to prevent litigation. Ultimately, it’s a memory play about the fallibility of memory, especially a traumatized memory, and how fragmented that can be.

Why did you choose a writer to be central to the story?

It felt like the most tangible form of a lie. There’s something about—yes, I’m a screenwriter and a playwright, but because I don’t write fiction or memoir—my opportunities to speak on my own experience are a bit more nebulous. They’re usually compressed. So it felt like a memoirist was the most direct channel to someone lying about their own story.

What do your personal reading and writing habits look like?

I’m always thrilled to talk about what I’m reading because I am an absolute nerd. In the last six years, the most consistent relationship I’ve had with any fiction writer is Melissa Broder. Her work is so sardonic and unfussy, but also speaks to issues in our culture. A lot of writers are precious when they write about disordered eating, sexuality, faith communities, and I just think she’s funny as fuck. I’ve read everything she’s written. I’ve read Death Valley, The Pisces, Milk Fed—I thought it was all incredible work.

I first fell in love with the fiction of Rebecca Makkai when I narrated one of her audiobooks, The Hundred-Year House. I fell in love with her then, but her most recent book, I Have Some Questions For You, I binged it. It reminds me of if Donna Tartt had unbuttoned the top button of her Givenchy blouse and taken a deep breath. She’s really unserious, but she writes about academia in a way that is as urgent and unforgiving as Donna Tartt.

I just bought a new book that I’ve not started. I’ve never read any Arundhati Roy non-fiction. She has a book called My Seditious Heart which is about political activism as a feminist, and her experience as a Brown woman, and her experiences in her home country of India. That’s next on the docket.

What has the transition been like from playing Devon in Severance to playing this character?

In many ways they’re hand-in-hand. The great thing about getting to do a character across multiple seasons of TV is you have the gift of time. You can put that character and her many nuances through a tumbler over and over again. The thing with the new play is that the emotional moments you find are not marbleized the way they are on TV and film. It’s iterative, and so there are moments with these characters that are different every night. I love that in theater writing, you as a playwright have very little control over what happens the way you might in the TV medium.

So many of the things I love about Devon—her warmth and her malleability and her compassion—don’t live in a lot of the characters in this play. It’s a very different world. She’s in an academic East Coast family, upper middle class, and this play mostly takes place in Kentucky with working-class folks who come from all over the world. There’s a Polish woman, an Irish man, and several Kentuckians. It was nice to pivot from that very lived-in, singular experience as her into this fragmented play.

Would Devon and the characters in Nothing Can Take You From the Hand of God have favorite books that they would like to share?

Oh my gosh, definitely. Devon would feel obligated to say her favorite book is The You You Are by Ricken Lazlo Hale, her husband, but low-key, she’s a closeted Franzen fan. That’s what Devon secretly reads. I feel she hides them from Ricken because he’d be, “He’s a bloated albatross,” or something absurd, and secretly she’s, “I know Franzen hates women, but he’s so good.” Maybe that’s just me speaking…

The characters—and I play 12 different characters in the play—most of them would say the Bible is their favorite book. Frances, the writer, is probably obsessed with Christopher Hitchens. In the play, when she’s introduced [at a] book reading, the fictional Terry Gross-type character who’s interviewing her says, “You’ve been compared to Weinberg, Hitchens, and Pinker.” That’s the milieu she likes to think she exists within.

What is one book you turn to when you are starved for inspiration?

I’m thinking of three; let me whittle it down. Etty Hillesum’s book, An Interrupted Life. Etty Hillesum was an essayist who was killed in the Holocaust. She was a feminist from the Netherlands. We couldn’t come from more diametrically opposed histories. I was raised a Christian in the evangelical South in the ’90s. She was a Jewish person in the Netherlands and met such a horrific demise, but her writing about reposing in the sanctuary of herself has been inspiring to me as an artist. She’s also just very funny.

What book was a formative read?

I read a lot of C.S. Lewis as a child, it started with The Chronicles of Narnia. Then, I read Mere Christianity and The Screwtape Letters, which now would not be inspiring to me because I’m not in that faith system, but his acuity for language was really beautiful. He was a deeply problematic person, the extent of which I didn’t understand until I was an adult. I would not say he’s a writer who inspires me now. But when I was a young Christian trying to figure out who I was, I remember thinking, This is beautifully curated prose, never mind the fact that he was a horrific asshole in real life. But, art from the artist, or something like that.

What’s one book that helps you understand the world we live in right now?

This Will Be My Undoing by Morgan Jerkins. There’s a book called Thick, a book of essays by Tressie McMillan Cottom, who’s one of my favorite essayists and commentators. I think she fucking hung the moon. It’s about her experience as a Black woman in a certain body type, and as a woman who has a complicated relationship with the American South and America at large. More broadly than that, she is just such a searing social critic about the bullshit of white liberalism, about the embarrassing nature of white female liberalism, and the pink pussy hat movement. She’s been a beacon for me [in] the way she talks about America and the preciousness of the American experience, especially for white liberals, and having to release that in order to look at our complicity in the current horrors.

What’s a book that’s ruined you in the best possible way?

Middlesex. I’m gonna say it, it’s such a cliche, but the end of that book. And The Borrower by Rebecca Makkai. I might get canceled for this, but I read Lolita when I was 20. Listen, there are all sorts of things to be said about how problematic the angle of that narrative is, but there was still such pain in the protagonist and all of the other characters. That was the first time I’d read a book as a young person and thought, I’m heartbroken over how terrible these people are. It hurt my feelings. I remember being apoplectic when I finished it. Certainly not a proponent of what Nabokov claimed to believe about the world.

That is part of reading. My relationship with literature is not necessarily morally aspirational. I’m as interested in books that say terrible things as I am ones that say things with which I agree. I would rather support the writers I think are trying to better the world, writers like Tressie and Melissa Broder, but there have been books that have moved me that I also morally disagreed with. That’s an interesting conversation we’re having right now in our country at large.

There are books by writers whose personal lives I don’t agree with. Again, I’ll throw Franzen under the bus. I don’t give a shit. Come find me, honey. Come find me at the Strand. His prose is beautiful, and his acuity for storytelling is beautiful, and he’s also a misogynist. As a person who claims to love books and who identifies as a writer, it is also important for me to understand why I responded to someone’s work who maybe believes something I believe is bullshit. What does that say about me? In a roundabout way, enjoying a book that was written by someone I don’t respect has made me look at myself as well.

Is there any book that you stopped reading in the middle and never finished?

I’m gonna be honest, I got about 20 pages into Arguably, and it was a book I was supposed to love, but it was so dense. It’s brilliant and it is Dickensian, but I found it laborious. I’m not a person who’s like, “I’m supposed to read this, so I’m going to finish it.” The idea is for me, but I couldn’t get it.

What’s one book someone should read if they want to get to know you?

God, I’m gonna roll my eyes at myself here so hard that they go back in my head, but maybe Mary Oliver just because I love her so much and I feel like she was such a queer icon with such a tender heart. I heard somebody once say, “Mary Oliver without ever having talked about another person spoke more to the human experience than any other poet because she was often just talking about animals in the natural world.” Growing up in Kentucky and finding solace in the woods, I would never begin to compare myself to her as a creator, but I believe in my heart what she wrote about and how she wrote about it.

And if you are writing a memoir, what would you title it?

My publicist is maybe gonna flick me in the throat here, but I’m working on some pieces that are based on my life, and the rough title is, You Shall Inherit the Earth, which was the name of the stand-up show I did a couple of years ago, and it’s a paraphrasing of a scripture passage. I like the idea of it because it’s about a false promise. It’s about the promise of a virtuous life and what a fallacy that is.

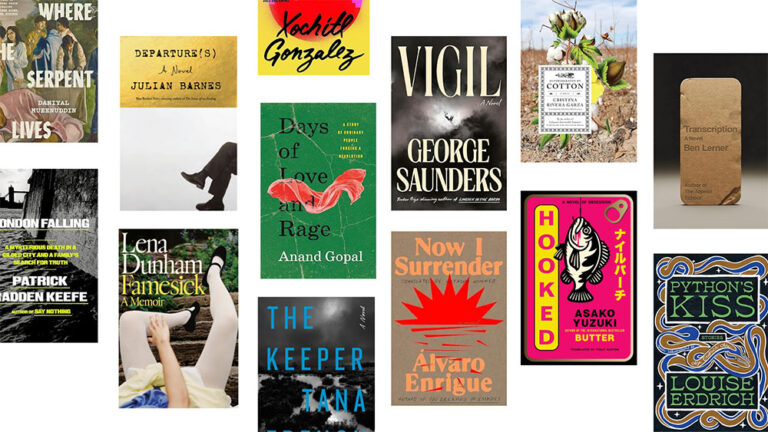

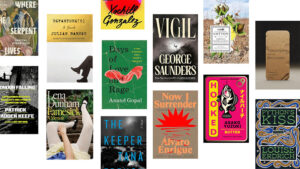

Jen Tullock’s Required Reading

Melisa Broder, Milk Fed, 2021

(Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, Starling Days: A Novel, 2020.

(Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

Rachel Kushner, The Flamethrowers, 2014.

(Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, 2021.

(Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

Jen Beagin, Big Swiss, 2023.

(Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

in your life?

in your life?