Chelsea is flush with heavy hitters and historical shows, doing what the neighborhood does best in its warehouse-scale galleries this month. While the most efficient walking tour based on these picks would start on 22nd Street and end on 26th (or vice versa), it’s not a bad idea to get your steps in, as they say, by beginning and ending at Louise Bourgeois’s jaw-dropper at Hauser & Wirth. Tip: to map our picks and plan your route, enter the Critic’s Table hashtag #TCT in the search bar of the See Saw app.

Louise Bourgeois

Hauser & Wirth | 542 West 22nd Street

Through April 18, 2026

Wailing fills the darkened first room of “Gathering Wool,” a two-floor exhibition of the artist’s work, most of it from the last three decades of her life. Grainy black-and-white video footage, from 1978, of actor Suzan Cooper’s pacing delivery of the song “She Abandoned Me” (from Bourgeois’s 1978 performance A Banquet/A Fashion Show of Body Parts) is projected against the gallery’s back wall, providing the moving-image and aural backdrop for an immense, motorized sculpture. Twosome, 1991, is constructed from a pair of black-painted steel tanks on a Stygian track. The smaller of the horizontal capsules slowly moves away from, then retreats into, the body of the other, while a red light strobes within. Here, a signature Bourgeoisian theme of (un)coupling is enacted at a terrifying industrial scale, in keeping with the artist’s anything-goes (yet totally controlled) scenography of the unconscious. Cooper’s singing adds an edge of desperate recrimination. Throughout the exhibition, curated by Philip Larratt-Smith, less severe objects (made from glass, marble, bronze, and all manner of found materials) are just as eerie, angry, sexual, and exquisite. In the next room, the wall-mounted fountain Mamelles, 1991/2005, never before shown in New York, spouts water from more than a dozen breasts.

The skylit fifth floor—day to the ground level’s hypnagogic almost-night—is host to Bourgeois’s more abstract works, a somehow-uncrowded embarrassment of riches (among them, a tower of weathered-wood open-storage boxes concealing two marble eggs, and cantilevered sculptures holding globes of blue liquid, rusty weights, and a spiky abstract charm). There are too many standout moments to list, but the exhibition’s most moving, lasting takeaway for me might be related to its opening curatorial gesture—that unhinged performance that greets you at the door. As, year by year, we grow more distant from a sense of Bourgeois as a living force and local personality (the artist, whose home and studio are preserved in Chelsea, just blocks away, died in 2010), the video underscores the social dimension and unprecious, wild qualities of her art. The show’s title work, Gathering Wool, 1990—a ring of seven mushroom-sprouting, boulder-size wooden balls positioned before a black, freestanding screen—is a somber, gnomic vignette, but it once functioned as a set: Another video, on the gallery website, shows the legendary actor-writer-painter Rene Ricard reading poetry, standing at the work’s center, the artist beside him. When he begins to unbutton his shirt for effect, Bourgeois encourages him to strip.

Milton Avery

Karma | 549 West 26th Street

Through December 20, 2025

Jumping ahead to 26th Street (I’ll circle back), another show to file under both “bananas” and “museum-quality” is “The Figure,” an expansive survey of Milton Avery’s still-jolting paintings, spanning the 1920s to 1964. The American artist is best known for the compositions of flat and simplified interlocking forms in seriously piquant and moodily unexpected palettes—the “Avery style,” a distinct approach settled on in the ’40s, was shared by his wife Sally Michel and later his daughter, March, both painters (as well as frequent subjects). The unchronological burst of canvases that kicks things off at Karma proves Milton didn’t always work this way, as do the wildcards peppered throughout, but his color sense always gives him away. In works from the ’30s, the “whites” of a man’s eyes are painted bright cerulean in a portrait otherwise rendered in sand and plum; a giant baby, of blaring bubblegum, is tended to by its blue-green mother against a ground of pea soup, and so on. While there are flashes of Picasso and Matisse everywhere, Avery borrows from them specific tricks and freedoms, not a logic. And because he painted without fealty to a movement (even as the New York School blossomed around him) his work remains hard to place in history. It’s the deep, unaffiliated eccentricity of his jigsaw-puzzle, out-of-scale compositions (including many curiously lovely domestic and seaside scenes) that make the canvases feel almost contemporary.

Tishan Hsu

Lisson | 504 West 24th Street

Through January 24, 2026

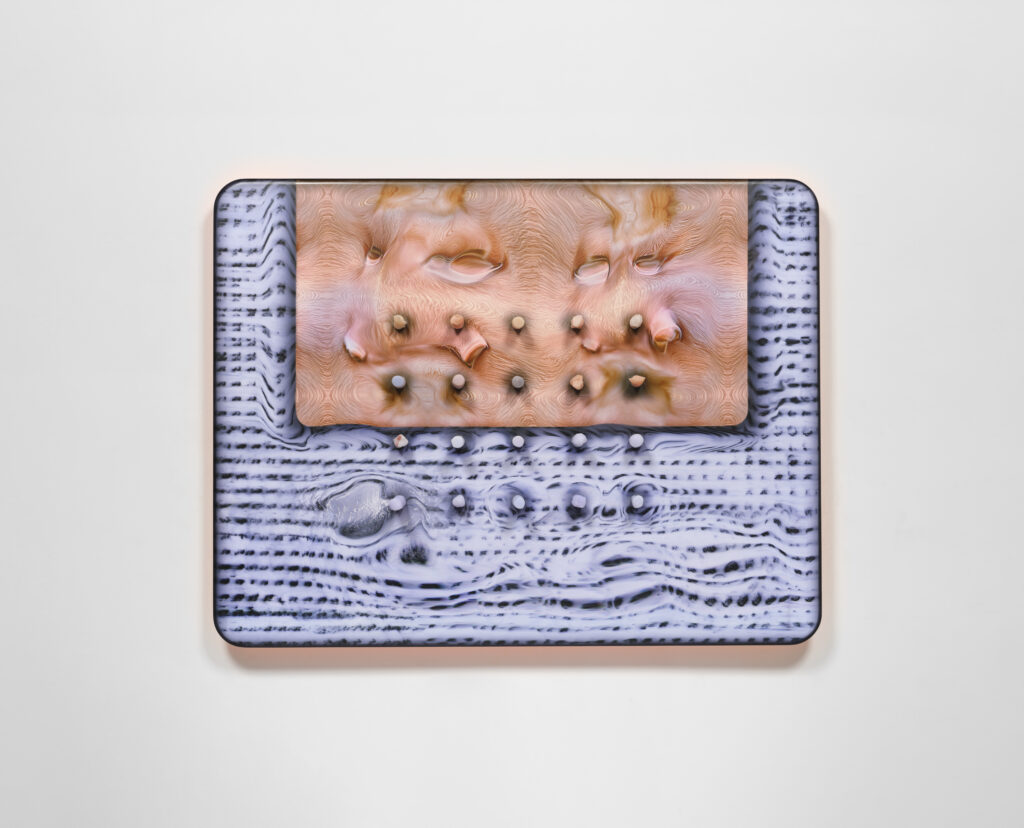

Backtrack to 24th Street for Tishan Hsu’s “emergence” at Lisson, which feels very now in a very different way. The artist, who came up in the East Village scene in the mid-1980s (showing with Pat Hearn and Leo Castelli before slipping from the New York art world’s view for a few decades), is often called prescient for his visualization of the interface between human and machine. Now, collective self-fulfilling prophecies abound, and Hsu’s woozy surfaces of circuitry, morphing orifices, and garbled protheses detail a future foretold by science fiction and body horror tropes that has more or less arrived. The work doesn’t wallow in or fetishize creepy aesthetics—Hsu’s commitment to his subject matter over time is palpable in the considered craft and material heft of his UV-printed, mixed-media painted reliefs especially. In these new panels as well as in a wall-spanning mural, fleshy pastel, grisaille, and lemon-lime iterations of hybrid organic-mechanical imagery (as well as silicone appendages) join op-art illusions of rippling space, while a billboard-size wall of LED tiles plays a digital abstraction generated in real time by a game engine. There’s an overwhelming vision, sensually dystopian and disturbingly familiar, at play. The body as data, the slippage between skin and screen, biomedical surveillance, the uncanny effacements of A.I.—it’s all impressively, viscerally evoked. To what end? I don’t know. But what’s flummoxing about Hsu’s art cannily mirrors the irrational excess of both his medium and subject-matter: oozing, reproducing, cutting-edge technology.

Alex Da Corte

Matthew Marks | 522 & 526 West 22nd Street

Through December 20, 2025

Returning to 22nd, you’ve got to see Alex Da Corte’s transporting “Parade,” which occupies the gallery’s two spaces with a pop-mediated waking-dream quietude. Staged as a series of chambers, populated by Da Corte’s avatars (a house painter in a Pink Panther costume, Popeye holding a pumpkin, and a corpse), the high-key environments tell an exacting, abstract story of psychic development or art history, in which the simplified and exaggerated, hand-rendered world of cartoons becomes a 3-D space of metaphysics or myth. At Matthew Marks’s 522 address, Pepto pink reigns as an animating substance (and embalming fluid) as much as a color, from the storefront “exterior” of the first room to the house-painting scene on the other side of its door, and finally to the breathtaking denouement of The Tomb, 2025. For this reinterpretation of Paul Thek’s destroyed 1967 work of the same name—a ziggurat housing a life-size effigy of the artist—an all-pink environment becomes unironically sepulchral. Da Corte positions what might be read as Barbie camp in a tradition of estranging replication and surreal decontextualization, as employed in the poignant conceptualism of artists like Thek and Robert Gober, as well as—perhaps you can see where I’m going, just up the block, back to the mother of them all—Louise Bourgeois.

in your life?

in your life?