When you walk into the Air de Paris gallery in Romainville, a northern Paris suburb, you don’t see much art. Instead, the first thing you see is people working at their desks.

“It seemed interesting to show our office and the way we work before going into the exhibit, but the employees don’t always like it,” says Florence Bonnefous, 66, the gallery’s co-founder. Sometimes visitors “force intimacy,” which is bothersome; at the same time, “it makes you question,” which she likes.

Bonnefous, who peers out from behind large, round glasses framed by a bleach-blond mullet, has made a career out of pursuing uncomfortable questions. In the process, she has become one of France’s preeminent gallerist-curators.

In the 35 years since she opened her gallery with the poet Edouard Merino, 64, in Nice, Air de Paris has become a sandbox for underground conceptual, challenging art and an incubator for emerging talent that might be considered too irreverent for more corporate outfits. Money “was never the goal,” asserts Bonnefous. Instead, she is interested in how art and life can “stimulate” one another and how to maintain integrity in an increasingly “corporate” art world.

“Florence occupies the rare position of being able to think like an artist while also representing artists commercially,” says Flint Jamison, whose exhibition featuring portraits of executives from Twitch, YouTube, and Spotify is on view at the gallery through Oct. 31. “Her unique form of empathy ensures that the questions and ideas at the core of each artwork are always prioritized—and these questions are weird and diverse.”

Air de Paris is exhibiting works by artists including Jef Gays and Monica Majoli at Art Basel Paris this week, but its relationship with the company soured slightly after the gallery publicly withdrew from Art Basel in Basel in June in protest of a substandard booth placement.

Yet Air de Paris has never minded being on the periphery—as long as it is on their terms. The gallery relocated to Paris in 1994, but then moved to a large industrial space in Romainville in 2019. Merino, the gallery’s co-founder, lives in southern France. He and Bonnefous met studying contemporary art at Ecole du Magasin in Grenoble, a program that trained a generation of forward-thinking dealers and artists, including Esther Schipper.

Air de Paris—named after Marcel Duchamp’s readymade vial of Parisian air—hit the art scene running in 1990 with a now-legendary exhibition featuring Philippe Parreno, Pierre Joseph, and Philippe Perrin. The artists spent a month in the gallery completing a “wish list” of things to do, from cooking classes to scuba diving in a collector’s pool. Although some accused Air de Paris of making “art for surfers,” according to Merino, the show put the gallery on the map. It also helped shape critic Nicolas Bourriaud’s theory of “relational aesthetics.”

“Even after one exhibition, the gallery already had a reputation,” said the artist Liam Gillick, who has shown with Air de Paris since its early days. In a testament to the close bond Bonnefous maintains with her artists, Gillick responded to a request for comment for this story with an email-meets-artwork listing 35 “points” about her.

Bonnefous has been “looking into ways of telling the history of art that is not linear, and that opens alternative pathways to writing what art history may be,” observes Donatien Grau, the curator in charge of the Louvre’s contemporary programming. “She epitomizes the curator-as-gallerist.”

The gallery has also been a staunch defender of avant-garde female artists Sturtevant and Dorothy Iannone early in their careers; it still represents their estates. “When no one got it, [Florence] had no question” about Sturtevant, the artist Trisha Donnelly said. (Donnelly has been represented by the gallery since 2002.)

Today, Air de Paris continues to push limits. Instead of participating in the last Art Basel in Basel, as the gallery has for 25 years, it withdrew via public letter after the fair moved its booth to an out-of-the-way location, a placement “which discredits us.” The “trend towards a more corporatist model has given priority to managerial efficiency, leading to new structures and new behaviors,” the letter added.

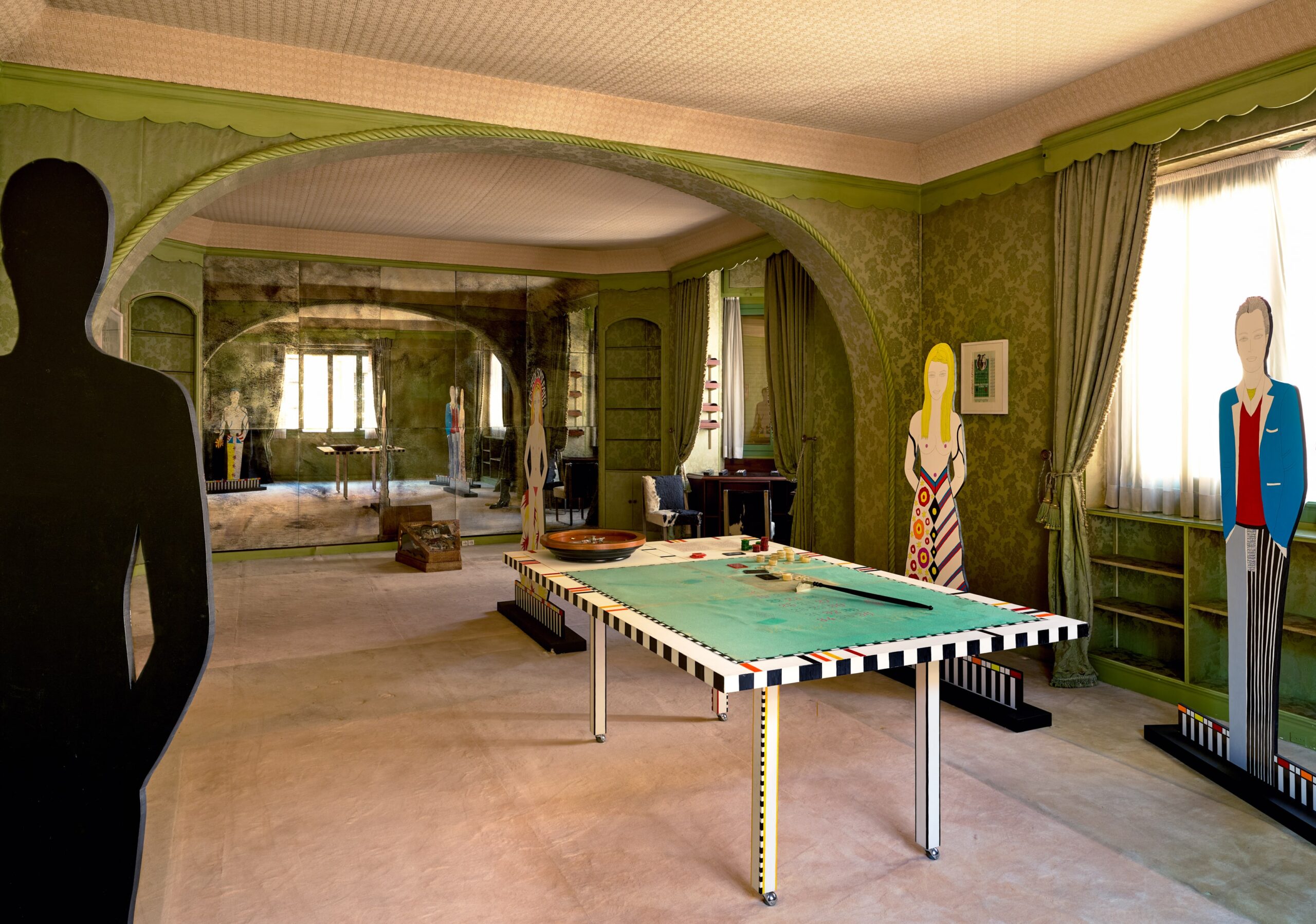

In lieu of the fair, the gallery mounted two summer shows, “More Just” and “Just More.” The latter took place in a velvet-draped flat near the Casino de Monte Carlo and featured a roulette table by Iannone, a Duchamp dolly, and the artist Michel Aubry dressed as a casino dealer.

But the corporatization of the art world is not limited to art fairs, according to Bonnefous. Many galleries “feel the need to resemble a predefined, corporate image,” she says. “It’s the white cube with an added ‘project room,’ to make it less white. If one is interested in art, they must abandon the idea that if a space is designed by a renowned architect, or Ruinart champagne is served at the opening, it means it’s a good gallery—it’s just not true.”

Still, Air de Paris has lost artists—including, most recently, the Portuguese artist Leonor Antunes—to galleries that have the means to finance larger projects. Two galleries also left the gallery’s Komunuma collective of four dealers—designed to lessen overhead and turn Romainville into an art destination—for Paris. But Bonnefous’s team is holding on, thanks to steady relationships with public institutions and loyal collectors.

Upstairs at the gallery, with her chihuahua DjoDjo in tow, Bonnefous walks me through the gallery’s exhibition of abstract paintings by Emma McIntyre. “It’s the first time I’m experimenting in such a strong way with the pleasure of beauty and contemplation when faced with a painting,” she says. The spaces hum with instrumentals from a Ben Kinmont film playing nearby, about the Northern California commune inhabited by a 1970s theater troupe.

As Bonnefous speaks, the rhythmic beeping of an oxygen-converting machine on her back keeps time. For two years, she has been living with COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease). While physically limiting, it has given her a new perspective—and inspired her to ask new questions.

She has been exploring crip theory and disability studies, and this spring, Joseph Grigely, a Deaf American artist who shows with the gallery and makes work about communication, will be featured in a show at the Palais de Tokyo. “I’ve come to realize to what extent people look at you differently,” Bonnefous says. Fittingly—and perhaps inevitably—“I’ve recycled this into a new point of interest.”

in your life?

in your life?