From the couch, the world comes to me in fragments—murmurs of the future tapping into our collective unconscious. In Neurotica, my new column for CULTURED, I’ll follow a theme I hear from my patients—a symptom, a fantasy, a refrain—through culture and into conversation. With each installment, I’ll also leave you a handful of recommendations for further inquiry.

What counts as human in an era challenged by artificial intelligence? As a psychoanalyst, I was taught to leave the terrain of the human and inhuman rather uncertain because it is. After all, the unconscious is rather inhuman—a little like a large language model. Attune to the anxiety of patients, I was told. Approach what is real and really challenging. But that was then. Now, we all have anxiety in spades, disoriented in such a wildly shifting technological landscape. Down the rabbit hole, we are Alice in Wonderland swimming in a pool of our own tears because we followed the directions that said, “Eat Me.”

I often wonder if I’ll see the new world in my lifetime. Reading about the spate of teen suicides assisted by A.I., the increasing number of cases of “A.I. psychosis,” including a matricide in Connecticut, I asked a fellow psychiatrist if this was portent of madness that would soon flood all our fragile psyches. “Women are also falling in love with their chat bots. A.I. porn will combine with the first external womb, while marriages are collapsing as partners use ChatGPT to diagnose their relationships,” I added with desperation. “Isn’t this the oldest story in the book? Teenagers feel hopeless, women manage arrangements of dissatisfaction, reproductive heterosexuality is growing obsolete, and men are easily adrift and grandiose?”

I do think something is new. It is as if we rang some “strange bell—jubilee, knell” to quote Emily Dickinson. All this technology is celebrated for its increasing frictionlessness, but it is making the experience of real life feel like agitation we can’t process. They do what you want, when you want, how you want it. Where is the pushback? Looking at the technology of his own times—which amounted to glasses, telephones, and trains—Freud thought man looked like a ridiculous prosthetic god. The satisfaction that came from technology was cheap, he said, like sticking your leg out of the covers and pulling it back in to feel warm. Little did he know about googling, scrolling, or swiping. I always think about the rage I instantaneously feel with broken printers. Or my weary patients, worn thin by online dating.

We are in a massive cultural experiment with what Freud called “the pleasure-principle”—the way our bodies organize pleasure and displeasure in life with others. We are being reprogrammed at lightning speeds, downloading this new world into our soma. Where are our bodies being snatched? The question sounds paranoid until you realize how much intimacy has already migrated online. To trace this digital libidinal history—and what it means for pleasure, fantasy, and control—I spoke with Mindy Seu, artist, theorist, and author of A SEXUAL HISTORY OF THE INTERNET.

Jamieson Webster: In your performance for A SEXUAL HISTORY OF THE INTERNET you speak about how sex workers were integral to the development of many digital platforms—chat rooms, e-commerce, webcams—and [how] their work was co-opted by Big Tech. I’ve worked with a lot of sex workers. They’re readers of desire, a bit like psychoanalysts. They take clients where they don’t know that they want to go.

Mindy Seu: With sex workers, there’s a way to frame this as a kind of victimhood: They are pushed into the margins, so they’re forced to innovate. But I like to think of it as a self-selecting model: These existing structures don’t work for them, so those who have more of an entrepreneurial or innovative sensibility end up figuring out new pathways. It’s helpful to see it in this way because they’re gravitating towards the development of certain new technologies like cryptocurrency.

Webster: What struck me a lot in your talk was the radical edge of digital life. Exploitation seems to happen through a seamless integration of tech into our lives, which is exactly what the people who were innovating—people on the margins—aren’t interested in.

Seu: Your point that sex workers are readers of desire is important because it suggests that they’re finding things that clients—and companies—don’t know that they want or need. As these new infrastructures are built, it’s typically done in a very grassroots way. They’re trying to figure out chat services or better bandwidth for streaming or different forms of payment that aren’t policed. Once it’s visible that there’s a marketplace for these things it becomes extremely commodified. This cycle happens over and over again.

Webster: I had dinner with the psychoanalyst Darian Leader last night. I asked if he was worried about A.I., and he said no. If this is a widely available technology that gives [people] someone to talk to, he didn’t see it as a bad thing.

Seu: Chatbots are really a mirror of a loneliness epidemic. But at the end of the day, I think what people need and want and crave is intimacy, and they’re exploring multiple channels for getting that. As the porn historian Noelle Perdue points out, no matter how extreme the ends of pornography are, the most searched position is always missionary. If we look at mainstream interests, general pop culture, it’s all relatively flat and easily digestible. And amidst all of this, culture will emerge on the sidelines for people who want more than this. I wonder if this is how these chat bots will be seen in the future? You hear these stories of people mourning the loss of their A.I. boyfriend or partner when ChatGPT updated.

Webster: People who used Replika call it the moment that their person was lobotomized.

Seu: On the one hand, this must feel horrifying. But on the other hand, it’s almost a safety. When Microsoft released its chat bot Tay, within a few hours on Twitter, it started to spew the most racist statements. It’s because these things are trained on large language models that have a lot of racist dataset points. When YouTube’s algorithm was first released, it was the opposite of what we know now. All the recommended videos would get broader instead of more specific. But then they realized that it wasn’t very addicting. From there, we saw the emergence of the algorithmic echo chambers that we’re very familiar with now. There are clearly a lot of dangers that emerge. But with all new technologies, I feel like there’s this period of people getting accustomed to what’s possible before they’re able to figure out what the breaking points are. And people are good at trying to find how to break the tool.

Webster: Artists always pick up a technology and try to figure out how to break it very quickly. They usually have less moral panic. I don’t know where I stand. Darian Leader didn’t understand why I was so taken aback. I worry a lot about the seamlessness of technology. Life is very agitating and aggravating, and we must work hard to metabolize life. I feel like technology sells us something that’s the opposite: making life feel infantilizing. You yell at your technology and try to make it do what you want it to do. You have a very master/slave relationship with it. It’s the un-rupture that I’m concerned with.

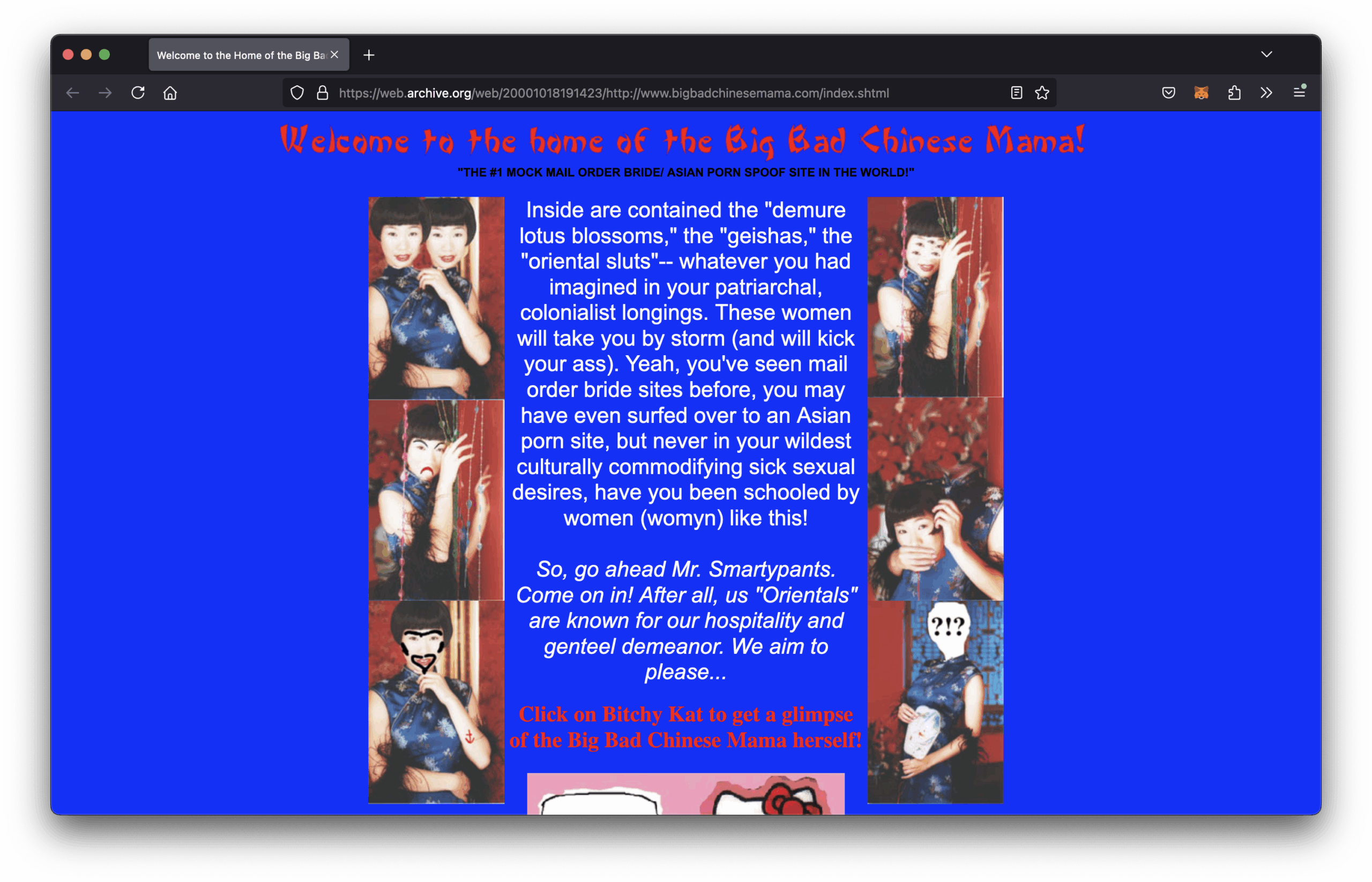

Seu: That phrase “rupturing the symbolic” comes from A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century, by the first reported cyberfeminist collective, VNS Matrix. When cyberfeminism emerged in 1991, two years after the introduction of the World Wide Web in 1989, they were already commenting on this infantilization or seamlessness that you’re thinking about: how cold, sterile, and militaristic these exchanges are. They were trying to inject the Internet with the slimy viscera of the body, especially in visuals and language. It was a very punk ethos. When you look at the evolution of cyberfeminism, you see how this shifted quite quickly since the ’90s. With Web 1.0, you had to know how to code and how to host a website. But in the early 2000s, with the rise of Web 2.0 and the rise of platforms, suddenly you could read anything. You could just put something on a blog or a template. On the one hand, it was democratizing because now anyone could make a website, but on the other hand, you started to lose the piece behind the curtain.

This is intensified tenfold with the platform oligopolies now. I still believe there are ruptures, but it’s so small because the tools have become so ubiquitous. You have these tools that are emerging that are very grassroots, but will they ever compete at the scale of a Google? Probably not, but that’s not the intent. Meanwhile, we’ve seen this return to dark forest or domestic cozy or all of these terms that Internet theorists use to talk about a return to the extremely exclusive, invite-only channels that try to reclaim what a subculture might be again. You’re not going to find that on Instagram.

Webster: I saw Paul Chan’s presentation at [the Aspen Art Museum festival] AIR of an A.I. version of himself, an LLM trained on his own data—writings, interviews, emails, texts, etc. He was annoyed at the way they produce middlebrow language, so he infused it with his favorite romantic, soft porn novels. He wanted it to debate itself constantly in the background so that it wouldn’t just spew certainty. He wanted it to be more pithy, so he trained it on his liner notes. He wanted it to be him, so he wanted it to be wilder.

Seu: You hear this often about rewilding the Internet. Is it possible? With Chan’s project, you’re seeing both of the two points: making something hyper-specific—in this case, it’s him, but it could be a small community—and learning how to use the tools to make something your own. Most people who use LLMs now just use canned data sets where you don’t actually know what’s in it, just that it’s big so it gives you the impression of being quite objective, that it is a neutral data set when that’s clearly not the case. I think understanding how to make an LLM specifically on key data sets that you curate is an important action. There are also the “ethical data” sets of Holly Herndon and Matt Dryhurst created using only public domain data.

Webster: What do you think of the future of Internet sex?

Seu: Mistress Harley coined the terms “Techdomme” and “data dom.” Data doms don’t do any in-person work. No physical touch. She doesn’t do any camming. There’s no nudity involved. It’s only about the exchange of power and humiliation play. She will get remote access to her sub’s machine, and she can control their computer. The sub can watch her move their cursor. She has access to all their hidden folders, their bank accounts. She has been banned from every single platform, every single payment processor, even though she’s quote unquote not having conventional sex. It’s ironic because while she sees what she’s doing as sex, an institution certainly wouldn’t. They understand intuitively that there is a power play happening here, but they’re not quite able to describe why it might be sex work.

Webster: For Freud, all fantasy somehow is a fantasy of being submissive because even if you’re a dominant, you still have a submissive part of yourself somewhere that you’re messing around with. At the end of the day, the hardest thing to do is to speak from the place of the submissive because you’re the object. The object doesn’t speak. The subject speaks. But you experience pleasure more as an object, a body being used as it were. The promise of technology is the opposite. It’s domination. It’s mastery. What a collision of forces, all these people running around online trying to figure out how to submit!

Seu: Before you join a platform, you have to check that you’ve read the terms and conditions, and that checkbox is meant to indicate that you’ve read it all, understand it, and consent to it. No one reads that language. They likely don’t understand the legal speech that’s required to understand terms and conditions. If you look at other models of the BDSM community, for example, that is not how consent works. Consent is an ongoing, enthusiastic social contract that is mutable. You can agree to something, experience it, and then decide you don’t actually like it, and then you change the terms. But all of this needs to be in discussion in perpetuity.

Melanie Hoff, who’s an artist and sex cybernetic assist, says that when you have vanilla heteronormative sex, it’s perhaps the clearest example of non-consensual BDSM because you are just having sex the way that you were trained by a heternormative society without the conversation. Regardless of whether you’re doing anything kinky or not, it’s important to understand how to talk and negotiate the terms of pleasure.

Webster: So basically our whole relationship online is a non-consensual BDSM vanilla sex experience. We’re just doing what we’ve been trained to do.

Seu: Yes.

Webster: That’s where I thought we were, and that’s what worries me. Even if it’s helping with the loneliness epidemic.

For further study…

- A hilarious investigation into whether having several artificial paramours is cheating in The New Yorker.

- My friend and author Fiona Duncan on the woman artist behind one of the first chatbots, ELIZA, and a whole history of A.I. therapy (I make a cameo).

- British psychoanalyst Darian Leader’s new Substack, where he writes about A.I. therapy keeping psychoanalysts on their toes.

- Zoe Hitzig and Paul Chan on A.I. at the recent AIR festival in Aspen.

- A look into how A.I. sycophancy leads into delirium and sometimes psychosis.

in your life?

in your life?