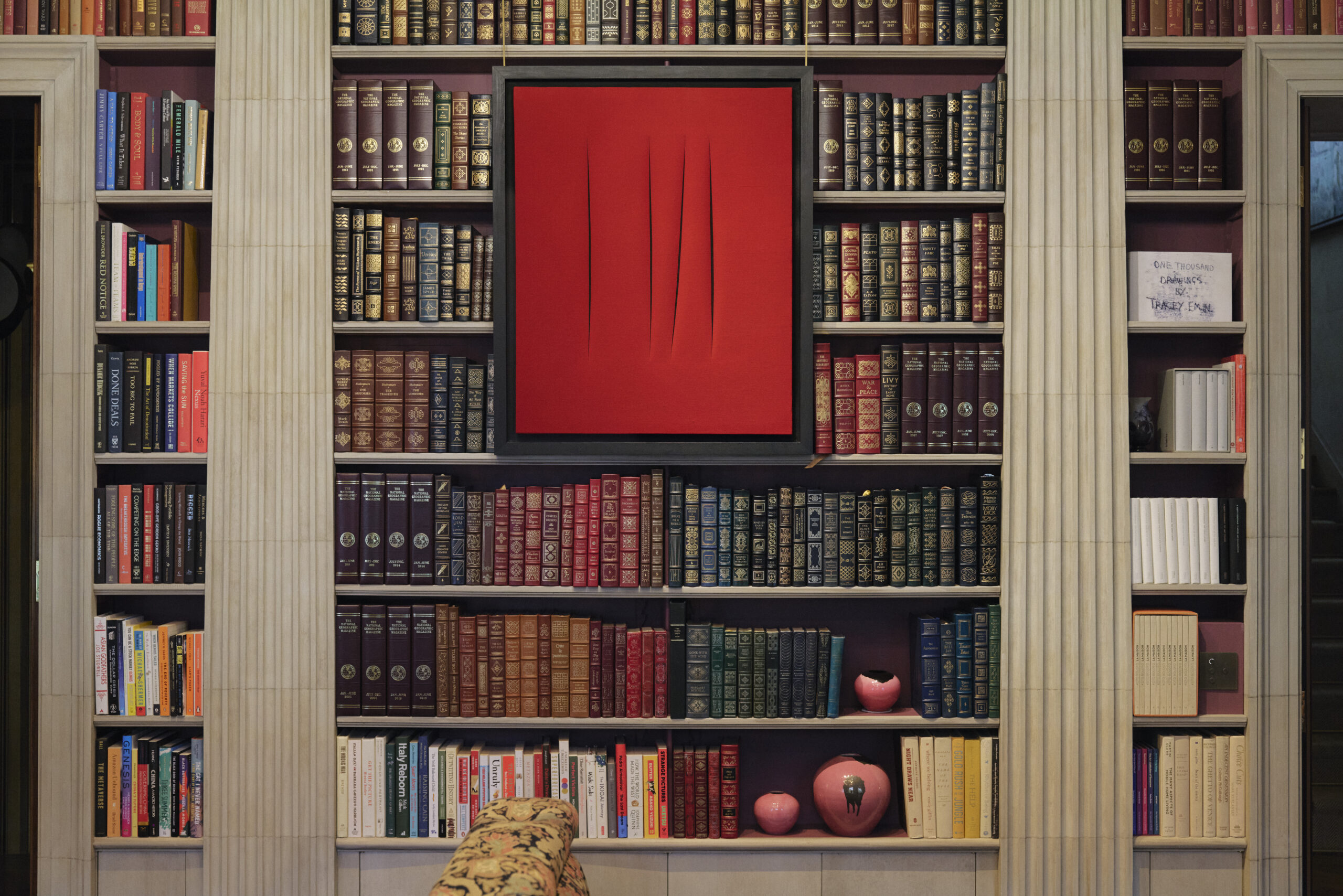

It is clear, from the moment you step inside Belma Gaudio’s London home, that she delights in contrasts. “We mix eras and styles,” she says, “From traditional Italian to modern French to contemporary, taking the best from each and putting them together in new ways.” Born in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Gaudio and her family fled the country when she was 8, living on multiple continents before eventually settling in the U.K.. Perhaps as a result, Gaudio has an eye for friction—between worlds, eras, and strains of creativity. As founder of Koibird, the London fashion, homeware, and wellness boutique, she’s built a platform where art and commerce meet and re-meet in continuous tête-à-tête. Koibird’s interiors are made over twice a year, allowing for continuous aesthetic evolution—an extension of Gaudio’s ethos writ large. As her home city ramps up for a busy Frieze week, Gaudio offered CULTURED a peek at her sprawling art-filled home, and explains how a childhood penchant for gathering anything from Barbies to cast-off snakeskins evolved into a formidable eye for collecting.

What, in your opinion, makes the London art scene distinct from other art epicenters?

I love its mix of historical and contemporary art. On one hand, you are surrounded by centuries of artistic heritage in institutions like the National Gallery and the Royal Academy, and on the other, you have the dynamism of East London’s emerging galleries, artist-run spaces, and great fairs. London also manages to support both blue-chip galleries and experimental collectives.

Which aspects of the art world are most interesting to you?

I’m fascinated by how certain artists suddenly become the “hot commodity.” Out of so many talented emerging artists, why do some skyrocket overnight—or why do we let them—while others build slowly? I’m intrigued by that dynamic, how market forces, perception, and narrative can create a kind of inflated value that isn’t sustainable, and how quickly it can all shift when the market corrects. It then destabilizes the whole system: artists get hurt, collectors lose confidence, galleries struggle, and the ripple effect feeds into the wider volatility that we see in the market today. It’s very dangerous for speculation to overtake substance, and it raises a bigger question about what value in art really means, which is a subject my husband and I are very interested in.

What was your relationship to art and collecting in your childhood?

I wasn’t surrounded by art growing up, but I was surrounded by culture. I come from Bosnia and Herzegovina, which I left when I was 8 years old and essentially became a refugee due to the war. I then lived in Bratislava, Germany, and settled in Kuwait, until I moved to the U.S. in my last year of high school. I loved collecting things at an early age, whether it was snakeskin scraped off the dead snakes found in the garden, or very special Eastern European paper napkins that looked like they were made of lace, to stickers and pictures [which came] for free in chocolate bars. I hoarded stuff. And I collected Barbies. I always collected and always loved interiors. In my first studio apartment in New York, I had the walls painted black, the rug was zebra, the coffee table was a lucite trunk, a four-poster bed was in the middle of the room, and then I had these fake Frida Kahlo portraits that added a pop of yellow and orange to the black walls. I always loved beautiful things that came together as if they were always meant to be together.

Describe the relationship between your work as founder of Koibird and your art collection. Do the two inform each other?

Koibird’s interiors have changed 16 times in the last 8 years, always inspired by art. Our first interior design of the store was like a millennial pink “De Chirico meets Magritte” painting, then we had a bright ombré redo à la Ugo Rondinone paintings, and we also had a Mexican mural artist, Rafael Uriegas, paint the whole store into a mural. Inspiration for Koibird interiors always starts with a piece of art or an artist. Looking at product through a creative lens influences everything I do, from the fashion to the homewares, and everything in between. Living and working with art gives you a unique perspective. Does art influence fashion or the other way around? It depends on the occasion!

Have you discovered a city or local artistic community in your travels that has sparked a collecting obsession?

I have travelled around Asia a lot, and I would say that’s when I really started getting into collecting objects, furniture, and design pieces. Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, and China all had a big impact on my collecting habits, and going to those countries really made me start collecting. I would never come home empty-handed—I remember one of my first furniture purchases abroad. I may have been 25 years old, and I was in love with a very large, teak coffee table from Bali that I had to send to London. It weighed so much, but it successfully ended up in my living room in Chelsea.

What feelings would you like your collection to inspire in the people who experience it?

I would love for people to walk into our home and feel the personality, the love, and the creativity that went into it, without ever feeling like they are in a gallery or a museum. It’s about making art a part of life—eclectic, inspiring, and approachable. Our collection is woven into our family home. At the same time, I hope it inspires them to see how unexpected combinations can create something unique. I have always been inspired by merging ideas, visuals, eras, and themes. We mix eras and styles, from traditional Italian to modern French to contemporary, taking the best from each and putting them together in new ways.

You’ve said that Koibird is about introducing and encouraging a sense of discovery. How do you discover new artists?

For me, discovering new talent (whether it’s fashion designers or artists) isn’t about following trends or chasing the hype. I’m drawn to artists who are in dialogue with what’s happening—whether in the industry, in the wider world, or within their own creative communities. I like work that doesn’t just exist in isolation but actively contributes to the evolution of ideas. The most exciting discoveries are artists who make me see something differently, who challenge my assumptions, and spark an unexpected perspective. I am also very lucky that I collect with my husband, who has similar ideas about what and how we should collect, so the dialogue between us is also a valuable one. I also have some “love at first sight” moments with certain artists, which makes me pull the trigger.

Which work in your home provokes the most conversation from visitors?

Probably the Michelangelo Pistoletto dining table he created for us, called Mar Mediterraneo, with all the different chairs around it that I have collected over the years. The table is in the shape of the Mediterranean basin, surrounded by chairs from multiple foreign countries, and the table is the first of its kind, while a smaller coffee table version was presented at the 2003 Venice Biennale. The idea of it is to love your neighbour no matter how different they are and how uncomfortable it is to sit next to them—you have to make it work, and love the differences!

What factors do you consider when expanding your art collection? And how has your collection changed alongside your home?

The number one factor we consider when expanding our collection is love. That has always been the guiding principle. As a result, we have ended up with quite an eclectic collection—pieces that may seem random side-by-side, but each one means something to us. Some experts in the art world insist that collections should follow a certain logic—by movement, era, medium, geography—but I don’t come from an art background, so I don’t feel bound by those rules. For me, collecting is not about fitting into a narrative; it’s about following instinct. And yet over time, patterns naturally emerge. You realize you have been drawn again and again to certain themes, so even a collection built on love and instinct reveals threads of continuity. When it comes to how the collection fits into the home, there is definitely a purpose and plan to what I buy. I buy with intention, and I do buy for specific walls, rooms, décor. Not always, but I generally have a plan for where a certain piece will go and how it will fit into the full story.

Describe your art fair uniform.

It’s all about comfortable walking shoes for me at a fair, so usually some kind of cool sneaker. And then I will challenge my otherwise comfortable outfit with an artistic piece: either a jacket, a top, or sometimes it’s the trousers that stand out. Last year at Frieze, I wore a top from Koibird that was like a black-and-white, mirrored Pistoletto painting, and it changed color in the sun. I have worn Issey Miyake artist series pleated dresses, and anything with color, paint, or something special about the garment. I like to jazz it up a little bit at the fairs. I am not the one all in black.

Which book changed the way you think about art?

I really enjoyed reading Linda Nochlin’s essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, where she dismantles the myth that greatness in art is purely about individual genius, and instead explains the institutional, social, and educational barriers that kept women from having the same opportunities as men. It’s not that women lacked talent or ambition, but it’s the systems and institutions that excluded them. It shifted how I look at both contemporary and historical art. It made me pay attention to whose work was overlooked, is missing from museum walls, whose voices are being heard, and who is pushing against those barriers today. Our collection, as a result, has become very heavily skewed toward female artists—but not because I was trying to hit a quota; it just so happens that a lot of the work we loved over the last years has been painted by women.

in your life?

in your life?