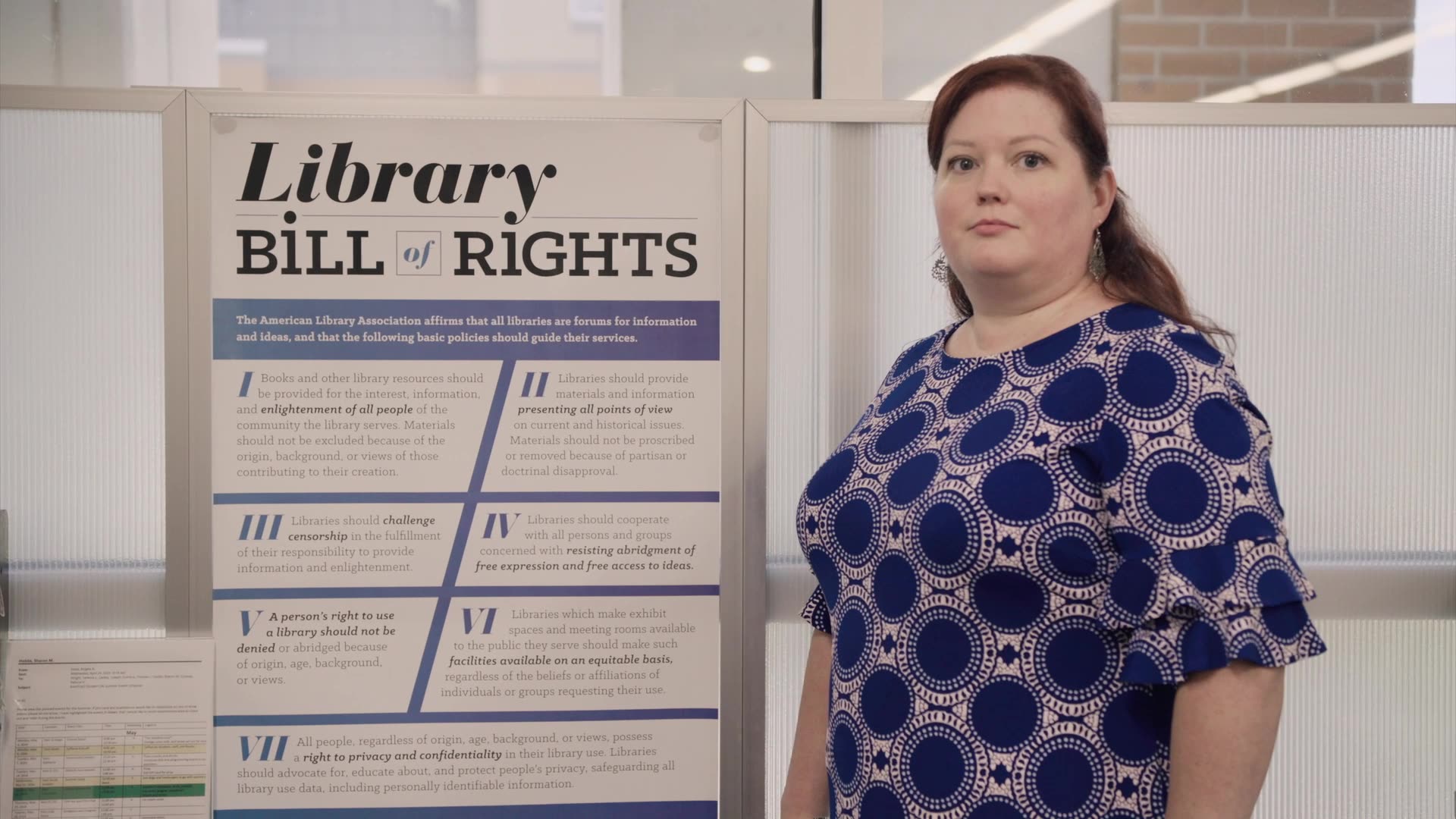

“A student’s mother was calling me a pornographer, pedophile, and groomer of children,” says New Jersey librarian Martha Hickson, in The Librarians. The smut she’s accused of peddling? The 2019 staple How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi, Harvey Milk: The First Openly Gay Elected Official in the United States by Barbara Gottfried Hollander, We Were Eight Years in Power by National Book Award-winner Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Amnesty International’s We Are All Born Free: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Pictures. These titles, along with about 850 others, were handed to schools by Texas State Rep. Matt Krause in 2021, as a formal inquiry into the holdings of their libraries.

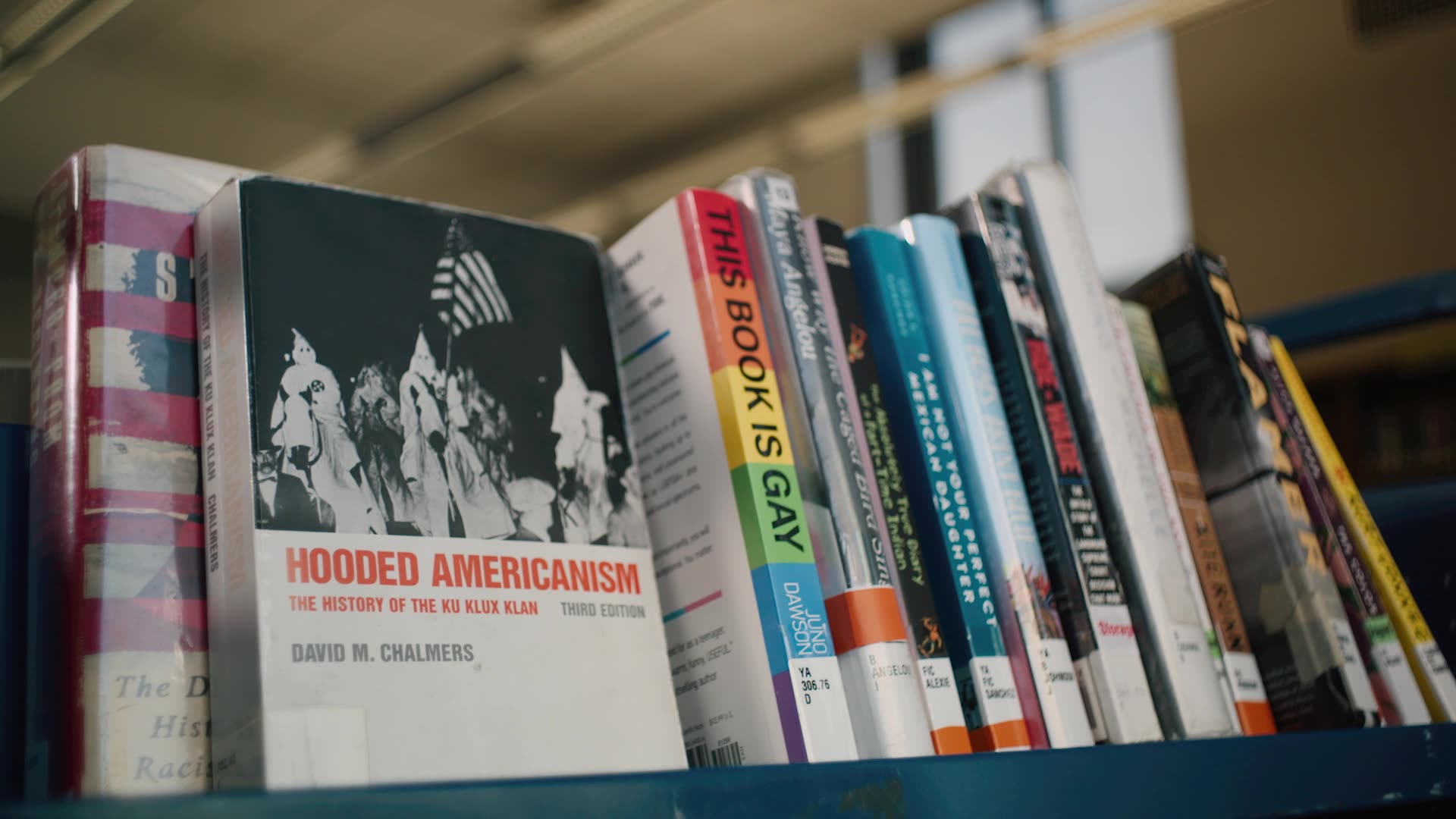

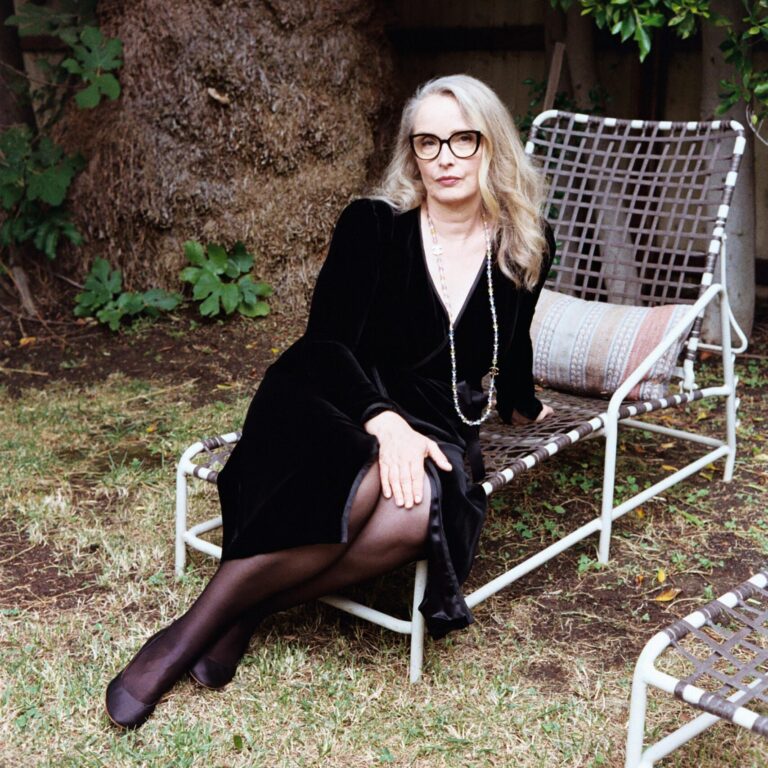

In The Librarians, filmmaker Kim A. Snyder follows the sweep of book bans across the country that followed, accompanied by organized attacks on school staff that led to threats, harassment, and in a number of cases, firings. “Here we are four years later,” says Snyder, when we talk ahead of the film’s theatrical release. Over 60 percent of the books initially targeted focused on LGBTQ+ subjects, followed by race and sex education. Since Snyder began filming, governmental support for this kind of censorship has only increased, with officials as high-ranking as the president calling for the removal of exhibitions focused on race from museums or fighting to ban oppositional reporters from the White House press pool.

Snyder’s film focuses on an unlikely group of rebels, librarians, who face down screaming parents, well-funded religious groups, and targeted hate campaigns with unwavering confidence in both their rights and their students. Here, Snyder offers a look behind the scenes of going out on the road to capture this uncertain moment in American history.

CULTURED: In your work, which includes documentaries focused on the Parkland students and other school shootings, you keep returning to what school kids are going through. What keeps you coming back to that age group?

Kim A. Snyder: My last films, Death By Numbers and Us Kids, were chronicling the youth movement that sprung up out of the school shootings in Parkland, Florida. I was so inspired by and honored to tell the story of some of those activists. Thousands of youth across the country were so understandably traumatized and angry about gun violence becoming the number one killer of youth in America. With the idea of an assault on freedom to read, there’s a commonality there about a fundamental lack of respect for human beings, for youth and their rights. The age group we’re talking about, middle schoolers and high schoolers, are at that really tender age of coming into being as young adults.

What’s striking a nerve about this film and this issue is an emotional connection. A lot of us have early experiences of those first stories in libraries. People argue all the time that kids don’t even read anymore. What’s the big deal about book banning? But we know it’s about so much more than the books. It’s about an assault on diversity, an assault on representation of all kinds: of people of color, or queer people. Part of being human for anybody is sometimes feeling alone and misunderstood. Being able to relate to a character in the book—whether it’s because the character reminded you of yourself because you’re a girl or because you’re Latina or because you’re Black or because you’re queer, or because you share personality traits—is so important.

That’s where this story became so poignant. There were these brave librarians who are so committed to the rights of kids and understand these books do save lives. I came to a part of the story where Amanda [Jones], a librarian in small, one traffic light town in Louisiana, told us that she has lost 12 students to suicide because of feeling othered. When you’re going after the books, you’re really going after those kids. And they feel it. They understand that if you don’t want those books on the shelves, you don’t want them.

CULTURED: Did you grow up going to libraries? What were your first stories?

Snyder: My father was an artist, and my parents had an art gallery. I remember being as young as seven, and they would leave me at the library. It was a very safe space, metaphorically and literally. It was in Princeton, New Jersey, where just yesterday, the public library requested my new film, not knowing that I actually spent all those years in that beautiful space. I was a kid that was thirsty for knowledge. I remember learning the Dewey Decimal System and compulsively going through every book I had in my bedroom and making my own little system so that I could have a legitimate library. As I got a little bit older, I loved Slaughterhouse-Five, the [Kurt] Vonnegut book which was later banned. And I loved Toni Morrison’s books, which also appear on banned book lists now.

CULTURED: The film does a good job of conveying the shock that curiosity and spaces for learning are not considered American values anymore.

Snyder: There’s deliberate misinformation that there is obscenity in the schools and libraries. There’s all of this use of language like “indoctrination” about asking for pronouns in the classroom. That’s not what this is about. This is really about representation. We need to reclaim phrases like “parental rights.” Librarians never had a problem with certain parents saying, “I’m not so sure that I want my 10th grade kid reading this book that has sexual assault.” They could have a conversation. There was a process. Now the process has been brazenly broken. Librarians once had zero challenges to books on the shelves—now they have hundreds.

There’s that age old quote: First they burn the books, then they burn the people. When we take certain books off the shelf, what does that mean for our democracy? Many of us feel that the freedom of expression has gone beyond the libraries. It’s in the museums now. It’s in our institutions of higher education. It’s on our late-night talk shows. Freedom of expression is under threat.

I’m hoping the film reminds us that the values that our nation was founded on are not a partisan issue. One of our librarians was brought up staunchly Republican and Christian. The two things that she was taught to stand up for were First Amendment rights as a Republican and to love thy neighbor as a Christian. And she said, “I was attacked for upholding the very things that my household and my community told me to fight for.”

CULTURED: What kind of response has the film gotten so far?

Snyder: We’ve had this incredible festival run both here and abroad. It’s been almost all positive, but now we’re going more public. Much to my surprise, in a time when there’s not a lot of theatrical distribution for a little independent doc, our trailers had over 1.3 million views. We are now booked in over 70 cities throughout the country. That was way beyond what I was told to expect.

But I know that online, there’s new concerns about our security as we travel with it. I never thought I would have to worry about that. It’s not like I’m covering the Taliban. Yet a couple weeks ago, the day after the really tragic shooting of Charlie Kirk, one of our librarians and I were meeting in New Jersey for a screening and some of her opponents went online and started to threaten that they were going to show up and disrupt the event. I don’t think you have to take all these things seriously. But there’s such a concern about normalized violence. An old friend provided security, and I immediately told the librarian, “If you feel uncomfortable, do not come. You need to feel comfortable.” These are all things that we’re gonna have to decide as individuals.

CULTURED: In the film, one librarian does mention, “If you had told me a few years ago that there would be security at a conference for librarians, I would’ve said that you were insane.”

Snyder: I said for the last few years to friends, if you really wanna get a pulse of what’s happening in America, go to a school board meeting somewhere in the middle of the country. You’re not gonna get it just hanging out on the Upper West Side. Making these films has made me believe that there is a way of reaching the middle. Part of being a good citizen in the moment we’re living in is to be open to having conversations with people who might not have the same beliefs.

That’s part of the healing that needs to happen right now. I do it in every opportunity I can: outside of the city, in cabs and Ubers, as I travel across the country with the film. You learn a lot. With the gun debate, I know it’s possible to have conversations with people who have really different political beliefs than you do. You can agree to disagree and still have respect, unless someone’s really spewing hate. We clearly have a dysfunctional system right now. If our politicians can’t reach across aisles, we have to try.

in your life?

in your life?