Nayland Blake

Matthew Marks Gallery | 522 & 526 West 22nd Street

Through October 25

Just before sitting down to write about Nayland Blake’s “Sex in the 90s,” a retrospective curated by Beau Rutland at Matthew Marks Gallery—the most major of the presentations in the artist’s three-part event this fall—I went back for a last look with a young gay artist whose work in some ways unknowingly calls back to Blake’s. (Maybe figurative painting isn’t exactly in eclipse, but it’s not quite the inevitable redoubt of identity anymore. And as it wanes, a recurrence of postconceptualist sensibilities c. 1992 is perhaps unavoidable.) My friend remarked in an anodyne tone, “Cool group show.” Is it a lieu commun that a Nayland Blake show tends to look like a group show? Their exhibitions rarely read as unified by style or form; instead, they operate like polyphonic theatrical stages wherein disparate objects, moods, and references rub against one another. For Blake, that multiplicity is not an accident but a principle: queerness itself enacted as an aesthetic method.

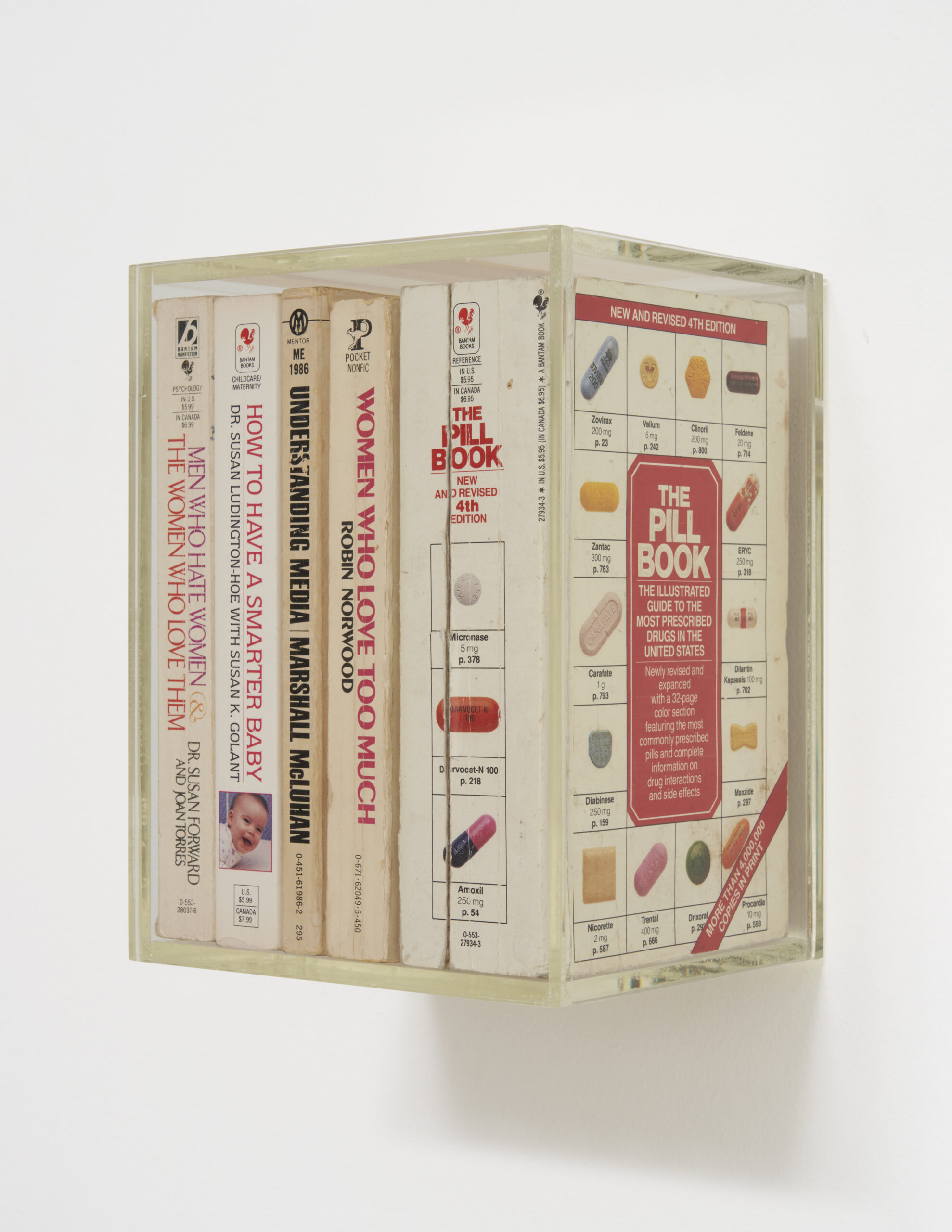

On view in the focused survey (at the 522 West 22nd Street space) are things as varied as wall-mounted plexiglass boxes encasing groups of mass-market paperbacks (Women Who Love Too Much, Helter Skelter, and Myra Breckinridge among them); a cluster of framed graphite-and-colored pencil drawings; a yellow stuffed bunny with pom-pom Kaposi sarcoma lesions (Go, AIDS!); a David Hockney quotation silk-screened on a chalkboard and reeking of Joseph Kosuth and pedagogy; sculptures composed of steel enclosures resembling small animal pens; a canvas strait jacket-like garment, mocking and adopting “formalism” à la Richard Tuttle.

The through line here isn’t visual consistency but subject matter and attitude. Blake’s work propounds resistance yet admits subterfuge, as well as evincing an interest both poetic and anthropological in the conventions and paraphernalia of something that an ancient friend of mine used to call “the leather and fetish lifestyle,” his tone streaked with acidulous sarcasm. (This friend had his own dungeon. It looked like the Eagle re-done by Roger Corman.) Lifestyle sounds so retardataire—is Blake’s radicalism to restore it to the center? I mean, that is the truth of many of our preoccupations, Toril Moi aside.

In the second, smaller gallery at 526 West 22nd, in the back room (appropriately), an installation of new sculpture, titled “Session,” most explicitly draws upon a kink lexicon. Artisanal implements of pleasure/pain and roleplay accessories, both plausible and absurdist, even folkloric, are clipped to wall-spanning lengths of black chain—like Sadean, Brobdingnagian charm bracelets. And, like real, wearable charm bracelets, these too have the air of personal narrative, sentiment, autobiography. It’s almost impossible for your art not to if you’re gay or queer or trans, etc. However fanciful, fiendish, abstract, vitriolic, or assiduously distant it may be, if it engages the realities of your life, the art inevitably touches upon autobiography—or lifestyle. Francis Bacon went to extremes. Still, for all the fancy gilded frames, his booing Princess Margaret at Lady Rothermere’s ball, the endless dinners at Wheeler’s and vomiting drinks at the Colony, Bacon painted a pretty quotidian reality too, viz., his lover George Dyer’s suicide as it tattily was, with Dyer seated or rather crumpled on the toilet. It’s this kitchen-sink and from-the-actual-life grotesquery that gives Bacon’s art its certain savor; otherwise, Surrealist and/or Expressionist disaster looks as predetermined or scripted as the characters of commedia dell’arte.

Meanwhile, in the front room, Blake has assembled a group show that serves as both homage and, in a way, prolegomenon to his own oeuvre, including mostly small-ish wall-mounted works, reliefs as much as drawings and paintings, with telling standouts by Betye Saar, Joseph Cornell, Richard Foreman, and Nancy Shaver. Lots of boxes: perversely, Blake’s group assembly looks at first glance like a monographic exhibition.

Blake has always understood their art less as a set of objects than as a way of staging relationships—between viewer and prop, history and parody, sex and humor. And, yet another way to describe the work is to foreground how insistently it engages with art history. In “Sex in the 90s,” the references come fast and thick: Dieter Roth’s decomposing chocolate sculptures and installations—he did chocolate bunnies too—Jeff Koons’s finish fetish, PC Richards & Sons vacuums, Pictures Generation-style album-cover art, etc. But what’s remarkable is Blake’s fast and knowing recapitulations of really recent precursors, like, people who are maybe only a half-art-generation “older:” Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Liz Larner, Robert Gober, Christian Marclay, and on and on and on. I made a list for “Sex in the ’90s”: 40-odd names. Walking through the show, I saw these echoes before I “saw” sex, insistently, irremediably. Frankly, I prefer Blake’s work the first way— though I know they’re genuinely and profoundly engaged with sexuality and alterity as a real-life thing, not as a dog-eared copy of Yale French Studies. (I love Yale French Studies and I’m sure Blake knows the special issue edited by Shoshana Felman, Psychoanalysis and Feminism: The Question of Reading: Otherwise, 1977.)

That delay in finding the eros here is revealing. “Sex in the 90s” calls up a decade of AIDS panic and safe-sex campaigns, feminist sex wars, protease drug cocktails, and Madonna’s Sex book—not to mention MTV’s documentary series of the same name. For Blake personally, it was the decade of writing porn reviews, co-curating the landmark queer exhibition “In a Different Light,” and forging the rabbit-prop and dungeon-studio vocabulary that remains central to their work. But the exhibition doesn’t simply illustrate that history. Instead, it filters the ’90s through the formal strategies of Blake’s contemporaries, producing objects that are haunted by both sexual politics and art-world memory.

This is why it would be a mistake to boil Blake down to manifest content. They are too smart, and frankly too gay, for such a straightforward reading. Their work thrives on the slippage between minimalism and dungeon, plush toy and fetish object, pastiche and sincerity. The bunnies and the chains all operate as props, placing the viewer in a scene that is never quite stable. You think you know what you’re looking at, then the script changes.

If a Blake show feels like a group show, it’s because their practice insists on porousness, on the way queer culture builds itself out of appropriation and recoding. They make art that looks plural because its subjects are plural and fluid: Desire, identity, and history refuse to stay in one place. And, of autobiography, the relationship between art and life, the artist explained in a 2013 interview, “If you look at that work as a way of mapping a simplistic relationship to identity it’s not useful. I think what we need now is incoherence. The drive to narrative closure is one of the things that is incredibly debilitating at this moment.”

in your life?

in your life?