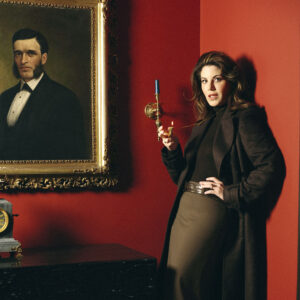

The same night filmmaker Nadia Conners met director Alexander Molochnikov, lauded Russian choreographer Mikhail Baryshnikov was in the audience at the latter’s New York production of Seagull: True Story. That’s really what Molochnikov remembers most (no offense to Conners).

Baryshnikov is a looming figure for Molochnikov: a fellow Russian living abroad, sharing the richness of his culture with American audiences and derided by his government for doing so. “He’s a rare reason for the big success of Russian culture abroad,” said the director. “The Russian media would constantly say … that he was performing somewhere in the Bronx on the outskirts of New York. Actually, he was on Broadway having a show with Liza Minelli.”

Molochnikov, meanwhile, left Russia after his support for Ukraine prompted death threats from the state-funded Wagner Group. “[They] sent me pictures of my parents’ houses and said with a text, ‘Be careful walking there, you might slip and fall into a pond,’” he told Conners when the two sat down to discuss Seagull and the play’s parallels to Molochnikov’s own immigration to the U.S.

In the play, a director faces censorship while staging a production of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull in Russia, and flees to New York with the hope of finding a more receptive audience. Instead, he is met with another, weirder form of repression. Molochnikov staged the show at LaMaMa last May, before moving it abroad to the Marylebone Theater in London, where it is set to run through Oct. 12.

Between curtain calls, he spoke with Conners about life before exile, the unexpected commonalities he found between Russia and the U.S., and the place of the theater in it all.

Nadia Conners: Can you talk about your history as a young theater director?

Alexander Molochnikov: I started at 22 in the Moscow Art Theater, which is the best drama theater in Russia. It’s where the play The Seagull started its life, directed by [Konstantin] Stanislavski. When Meryl Streep came to the [Moscow Art Theater], she kissed the curtain. It’s a very special place for the history of theater, the history of acting, and modern theater. I started there and did a play about World War I that is actually ironically still on. It’s been going on for 11 years now, although on the poster it says “Directed by Director” because after I supported Ukraine in 2022, along with other directors who did the same, our names are no longer written. They just say “Directed by Director,” which, actually, I think is a genius way to put it.

I was lucky the play was quite successful. I did about five drama plays in Moscow before the war started, and I did an opera and a ballet at the Bolshoi Theater. [The ballet] won the Golden Mask award, which is the main Russian prize for theater. We won that award a month into the war. It was very strange because when the war started, everything changed. Russia became isolated in terms of culture, in terms of economy, in terms of everything—it’s isolated from the Western world. My friends are leaving, but at the same time [there’s] this awkward feeling that your opera and your ballet just happened to be on the same day on two stages of the Bolshoi Theater, which is so great. On the other hand, it’s kind of useless because it was one of the cultural centers of Europe, and now it’s just an isolated, weird place.

Conners: Would you have moved if the war in Ukraine hadn’t started?

Molochnikov: It’s horrible to say, but in my personal case, the war gave a good push for me to do something I actually always wanted to. I also can’t go back now, which is quite sad. My friend, Evgenia Berkovich, is imprisoned. She’s a theater director, imprisoned for her play about women recruited to ISIS in Russia. Besides getting the Golden Mask award, it also got a grant from the Russian prisons so the play could go around prisons as a positive example. After the war, since she supported Ukraine, they flipped it and said the play was propaganda of terrorism, sentencing her to seven years.

Conners: There are similarities between your experience of leaving and [the lead character] Kon’s experience in the play. Borders can be hard to cross in the physical world, but art travels. What you did in your play expresses on many levels what happens when you take something from its home culture into another under these circumstances.

Molochnikov: In a situation of oppression, a situation of authoritarianism, we try to escape, and everybody has their own way. We can escape by running away, leaving the country, and finding another place for ourselves. We can escape through protest, going and literally hanging up posters somewhere, or you can try to find an inner escape and try to stay yourself as long as possible.

The third way is incredibly interesting, and the director I mentioned is a great example. She started doing theater in prison. Her lawyer kept pushing her to appeal, and none of these appeals ever worked. At some point, she was exhausted and said, “Okay, I’m stuck. Let me try to do something so that I feel like myself again.” She started doing theater with her inmates. Unfortunately, they eventually forbade her from doing even that. There are circumstances where it’s impossible. When I came to New York, I knew two people there. The first time I sat with some actors I had found through friends, we read Chekhov’s The Seagull. I felt so alive.

Conners: Looking at the Russian version and the American version [of the play], and a little bit about state-sponsored versus independently driven work—there’s good and bad with both.

Molochnikov: Somebody said, “To answer history questions, follow the money.” It’s true. We always talk about art as art outside of money, but art requires financing. In Russia, surprisingly, from the 1990s through the end of the 2010s, until the war started, [it] was probably the freest time for creators because there was massive government funding—unbelievable to Americans. Any Moscow theater could have about 12 premieres per year. We were rehearsing everywhere—rooms, staircases, corridors—somebody was always making a play. Then it started getting censored. The government finally said, “We’re paying, so we choose the music.” And when the war started, many things were restricted.

In the U.S., you can talk about everything, but to make a play financially, especially an experimental play that’s not purely commercial, is almost a mission impossible. The budget of this play, even with no set design, just flying plastic, cardboard, and curtains, is probably three or four times bigger than anywhere else in the world. You have these insane costs because of unions, insurance, safety, and it rarely comes back because it’s hard to do a show that starts making money. Both systems have their pluses and minuses. What I can say now, living in New York and London, is that it’s hard to make something of your own, but I’m sure it’s the only thing a director should be doing.

Conners: What role do you think the arts play in responding to the issues of our time?

Molochnikov: Art cannot exist outside of the time it’s made in. It doesn’t mean that it has to become political, but actually the border between political art and art, and where politics ends and life starts, is such an unanswerable question—especially when you think of it in terms of war. When a bomb flies into your house, is that politics or is that life?

Conners: [There’s] this overwhelming love that you have, that one has in the audience, for the Russian people, because you’re seeing the culture, you’re seeing the struggle, you’re seeing the choice between compromise and protest. It’s a collective portrait … Is your directorial style mindful of that connection, or is it something else?

Molochnikov: I do care and think about the audience. Sometimes, pushing away the audience is great, provoking the audience, making them feel uncomfortable, is a very important part of what we are doing. There was one comment in a review: “The point the play appears to make at this juncture is bizarre and ill thought out, seemingly suggesting that an American actor discussing the patriarchy and other social justice issues when producing theater is akin to the kind of artistic censorship you’d see in Russia.” I don’t think I need to explain how Kremlin authoritarianism differs from socially progressive theater productions in the West.

It’s wanting to deny and not look at things that do exist, which is just strategically wrong because, first of all, America has elections, which is a huge value. Many countries don’t, and Russia is one of them. In three years, there will be a chance to get another candidate running and winning, and for that, in my opinion, what should be done is [to] try to understand now, when we’re still not too far away from the previous election, what was done wrong. What was it in society that such a percentage of Americans voted for a very right-wing party?

Whoever is writing [this comment] is really turning away from a big problem because I did feel an absolute silencing of lots of things [in America]. I felt, honestly, sometimes more silent than in Russia because in Russia it’s very clear what you can’t say: you can’t talk about Putin, you can’t talk about the memory of World War II, you can’t talk about the Orthodox Church. In the U.S., it’s like a minefield. There are so many things everyone is afraid to talk about because we’re afraid society will turn against you. We’re afraid of a witch hunt. We’re afraid to say something that would offend someone when you didn’t mean to offend them.

Conners: There is this triggering thing that can happens, where everyone has to be careful what they say. We have to become a little bit more resilient as artists within our own community.

Molochnikov: We want to do art. We didn’t go to work in banking or sit in an office. I’m not saying that’s bad. I’m just saying it’s different. We went to do something that deals with emotion. Of course, Russian culture is very different, but we have a saying that you only become friends with those you fought with. You have a good fight, you drink vodka together, and you’re great friends.

in your life?

in your life?