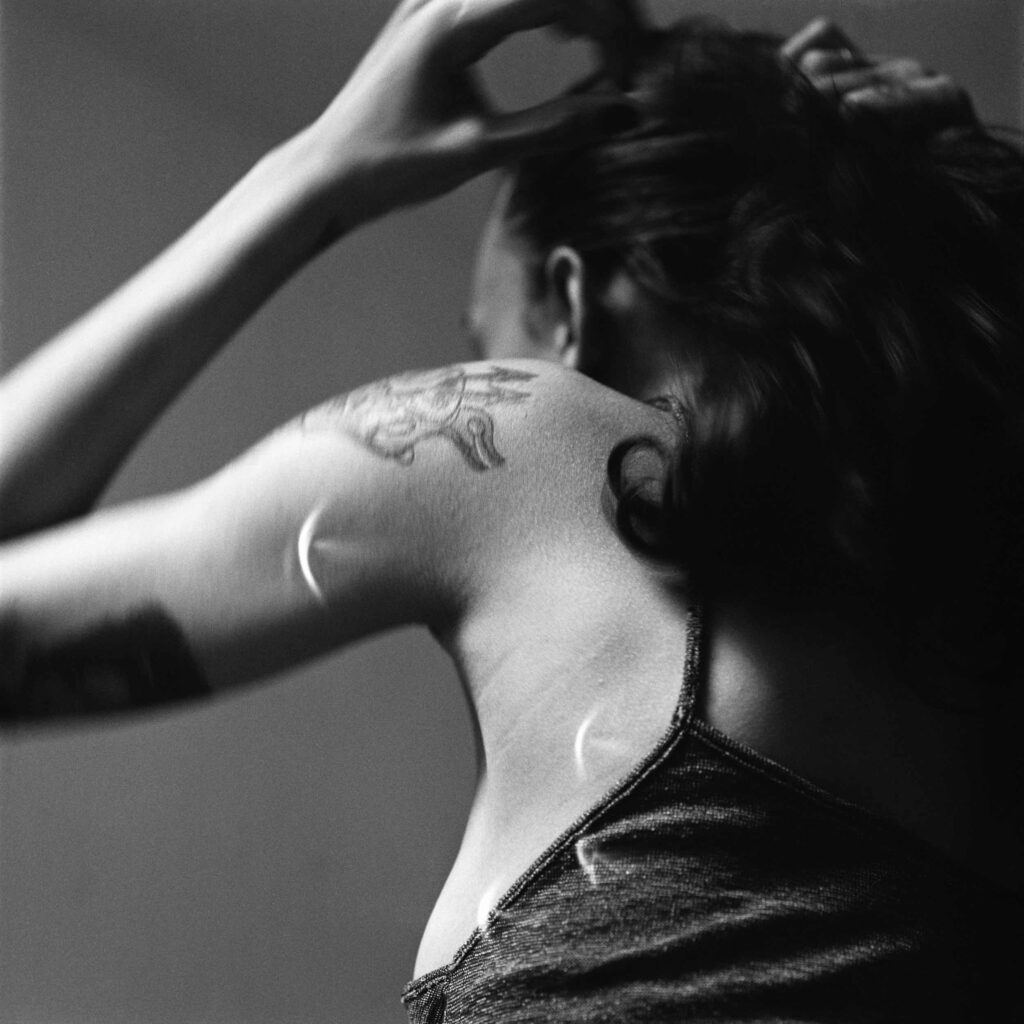

A lot has changed since 2011. Zora Sicher turned 16 that year; she’d traded Brooklyn’s tween punk-band circuit for the darkroom and was already well on her way to becoming one of her generation’s foremost documenters of intimacy, whether bodily or emotional.

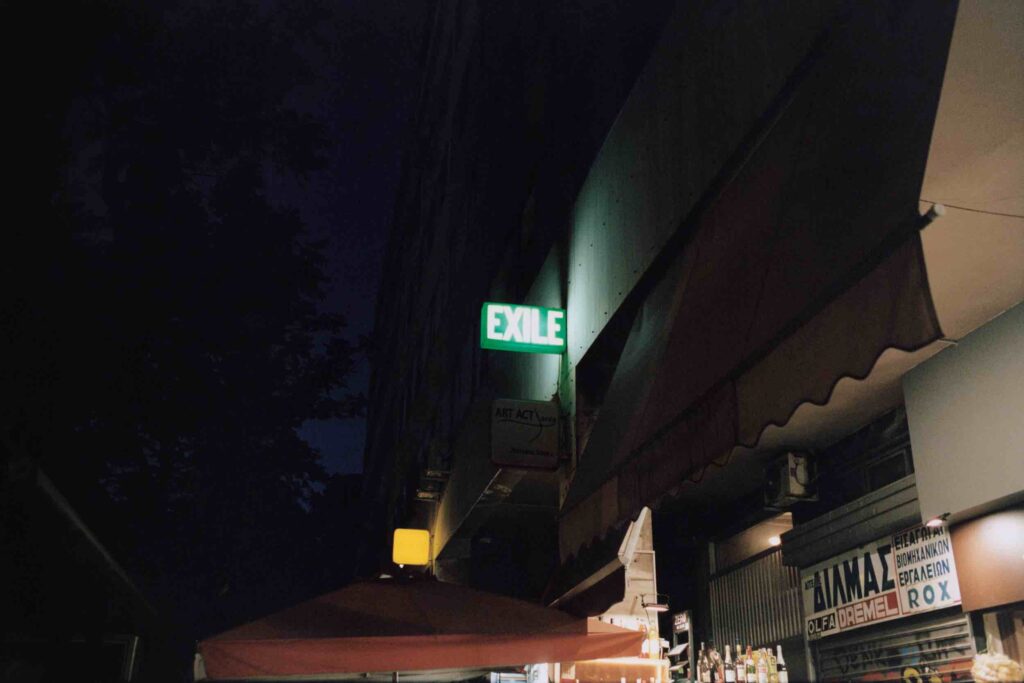

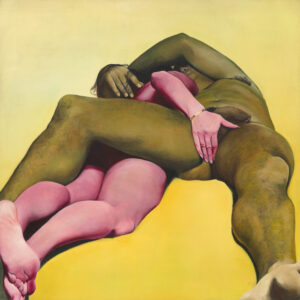

A year later, she would get her first tattoo with a friend, Eden. That matching ink is documented in the image, shared exclusively with CULTURED above, that closes Sicher’s first monograph, Geography, out this month with Dashwood Books. The tome sees the image-maker, who has worked with everyone from Paloma Elsesser to Marni, sift through the archive she’s accumulated since 2011—an exercise that revels as much in the peaks and valleys of growing up as in the act of making something together, whether that’s a friendship, love, or a photograph. It also marks the end of a chapter for the photographer, who is itching to move beyond the bounds of the still image. Before she does, and ahead of the opening of the Dashwood Projects show accompanying the book on Oct. 3, we caught up with Sicher hot on the heels of her 30th birthday.

CULTURED: This is your first monograph. You worked on Treasure with Paloma Elsesser a few years ago, but this is the first book that’s entirely dedicated to your work. How do you feel?

Zora Sicher: I just turned 30, and it’s really strange to have this come out after so many years of work. A good part of it is from when I was like 16, 17, 18. It’s been really interesting to pair those images with more recent work and also not be so precious with the work. It’s strange to have such a large body of work, and to try to respect the older work, when I had no idea what I was doing.

CULTURED: How did you balance the “not-wanting-to-be-too-precious-ness” with the permanence that comes with printed matter? And also coming to terms with imagery that might look very different from what you make today.

Sicher: When people ask what the book is about, I keep saying it’s about nothing and it’s about so many different things. It’s the kind of thing that wouldn’t really be able to exist without the passage of time. It’s not focused on one particular project or one subject. It took until now to go through everything I’ve ever shot, basically everything that still exists that I have, every negative, every scan, every print… And there’s a lot of shit in there! There’s a lot of stuff that I wouldn’t really show, but then there’s a lot of stuff that I’m like, “This isn’t a technically incredible image, but I’ve been photographing this friend since I was 16, and that passage of time is what’s important to me.” The older image paired alongside the image from last year is exactly what I want to show. I’m so sick of the word nostalgia when talking about photography, and I allowed one of the writers to use it in the ending of the first text in the book.

CULTURED: Why did you make the exception?

Sicher: I think I just liked how she summated everything. It worked at the end. But we talked a lot more about obsolescence and photography and holding on to things that are disappearing. It’s less about the perfect image; it’s about what that image meant to me at a certain period of time. Even if you can’t see that or detect what is older and what is newer. That’s part of the “map” of it all.

CULTURED: Can go back to 2011 and tell me about the early impulses and instincts that led you to what you were documenting?

Sicher: I remember that year taking my friend Eden and dressing her up and walking down Canal Street, and being like “I’m gonna make my own little fashion editorial.” I was definitely being influenced by the fashion image to a certain extent, but making it a little weirder and more, for lack of a better word, punk. Then I realized that I really liked to watch people and photograph people. It wasn’t as much about the clothes. What’s interesting about this book is it’s everything I’ve collected simultaneously and alongside feeding the fashion machine. There’s no models, there’s no “fashion” image in this book. This is the stuff that I’ve kept for myself for a long time.

CULTURED: What made you feel like it was time to share it?

Sicher: It felt like a couple cycles had to be closed. I spoke to a publisher, and it didn’t make sense to me. Then I started speaking to Dashwood really naturally after the Paloma book, and they were really interested. I just said, “I’m sitting on this body of work and I’m not really sure how to go forward with it yet, but I’d love to do something with you.” They were really open and really excited about the vague nature of it all. Right off the bat, it really felt right. David [Strettell] from Dashwood came to my studio one day—it was the first time we met outside of the shop—and I showed him this crazy PDF of so many images. And I was like, “I know this is really chaotic and it obviously needs to be edited.” And he was just like, “You don’t need to touch it. It’s a book.”

CULTURED: Were there any photo books that inspired you in terms of the format of what a monograph can look like?

Sicher: There’s this Hiromix book I bought that is fat and small with a hard cover. It looks like a Stephen King novel, you know? That one I remember really sticking out to me. There’s a Paul Graham book that was a big inspiration too. One of my first memories of Dashwood was when I was interning for Mario Sorrenti. He had put out this huge book called Draw Blood for Proof. It’s 30 by 47 cm, and it’s basically him photographing an installation he did that was collaging the walls of a gallery. So it’s just pages of photos of walls. I just remember thinking that was a really crazy book when they put it out at Dashwood.

CULTURED: How has your relationship to your subjects—and what you ask from them—changed over the years?

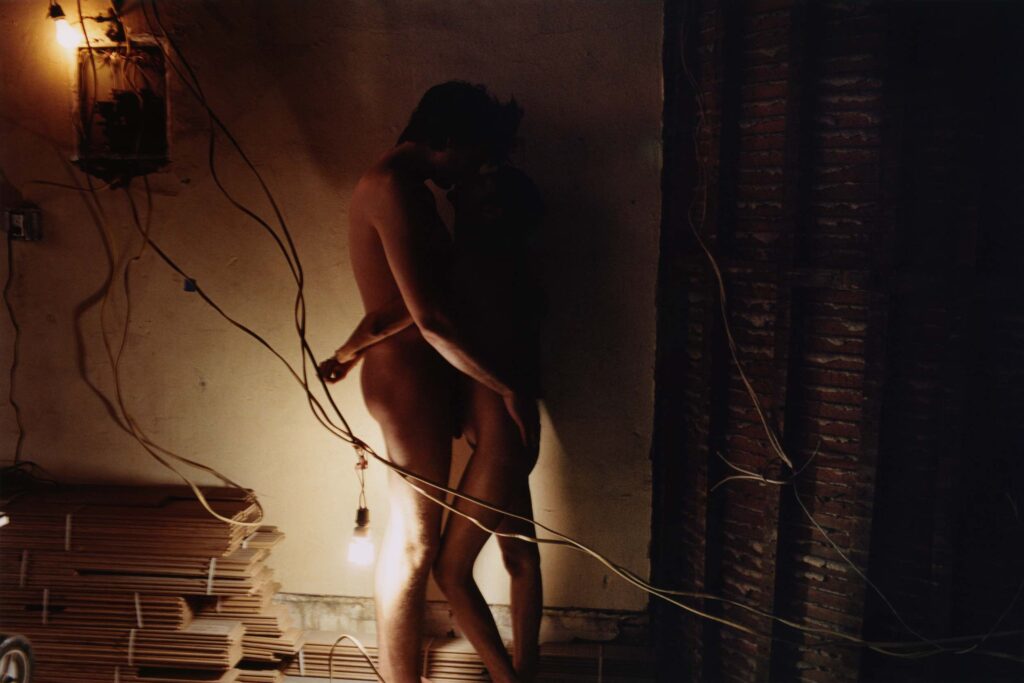

Sicher: Looking through the book, there are people who I’ve photographed for the entire span of the 14 years, or almost. Some of the earlier images are a lot more innocent in the sense that there are more candid images. As I got older, I think that the image making was more intentional or premeditated. A lot of the later images are not just coming from running around with a camera. It’s actually deciding to sit in a room with someone and say, “What are we going to get here?” There’s a couple people in the book who I met because I wanted to photograph them, or because they wanted to photograph me. I like when it’s collaborative. I want people to want to have their photo taken and for them to show me something I’ve never seen before.

CULTURED: Instagram was invented in 2010, a year before the first work in Geography, so the book also charts a parallel history of social media.

Sicher: What’s nice about the variety of images is when I look at some, I’m like, “That was such an innocent kind of moment.” Later you see that the way we’ve learned to consume imagery and looking at the body is so different than in 2011.

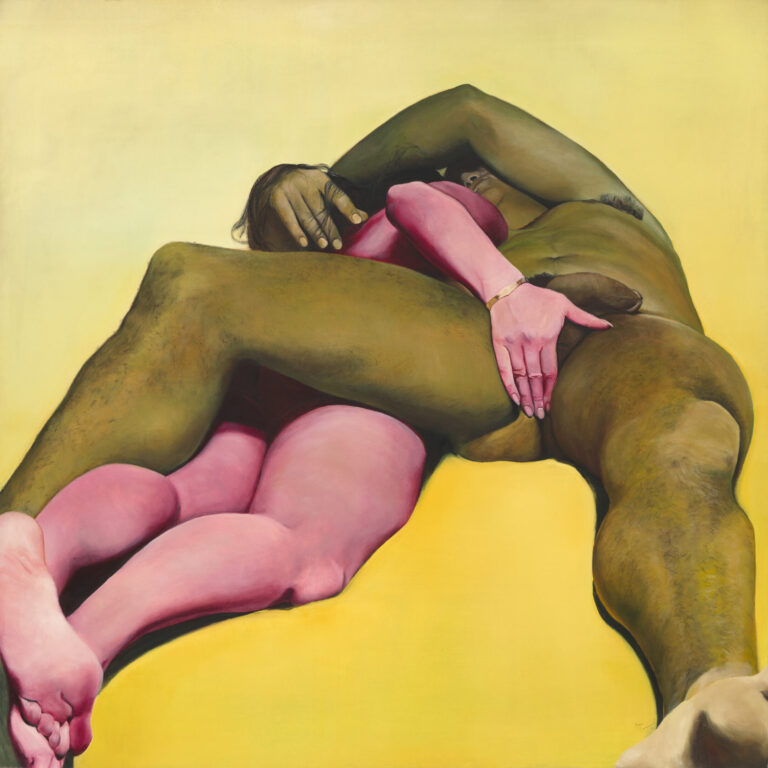

CULTURED: Bodies are more present in some ways today, but also more disembodied. In a lot of your images, there is a sort of bodily exchange that’s happening. But they’re not necessarily optimized or needing to look good or prove something. How has your relationship to screens and social media changed?

Sicher: There is this really dismal feeling. Part of the reason I felt I needed to get this body of work out now is because I’m losing it. There’s something I’ve grown away from in terms of photography. A big part of putting the book out is wanting to move on from it a little. I barely take photos for myself anymore. I’m way more interested in video and sound and writing now than in the photograph alone. The stuff that’s most recent in this book felt like the intention was to close the cycle. I’m a little disheartened by the over-consumption of imagery, and I don’t know what to do with it all the time. And I don’t know if I care to. I don’t know if I will start up a whole new photo book tomorrow. Maybe I’ll come back to photography again; it’s by no means an end. But the curiosity has extended elsewhere. For a great portion of the beginning years of this book, I was carrying a little camera around and obsessed with capturing every little moment and cursing myself when I didn’t have a camera. Later on, I began to think about, What is that urge to hold on to something about? What can I do with that that isn’t actually taking a photograph? How can I be present and then go home and make it into something else?

CULTURED: The photograph that you don’t take is almost as important as the ones you do take.

Sicher: Totally. We’ve gotten into this culture of just showing everything all the time. If it’s not being shown or shared, it doesn’t exist, or it’s not important. The way we all use social media now is proving that. Branching out into other mediums also comes from being a bit exhausted by just one format of sharing things. That’s where the writing comes from. And I haven’t decided I really want to share the writing stuff; maybe that’s just for me.

CULTURED: What do you want next for yourself?

Sicher: On Oct. 3, we’re opening a show that co-collaborators are curating at Dashwood Projects, which is complementary to the book. We’re trying to kind of do something a little different that goes hand in hand with the book. After that, I really want to nurture this writing practice more. People keep telling me that I should share things. So maybe next is a book of writing or poetry. I would love to work with a gallery. I would love to do a residency somewhere and work on video installations. I want to do something that’s out of my comfort zone and give myself the time and resources to actually do that.

in your life?

in your life?