Art can’t reverse climate change or restore a lost species, but it can shift how we perceive the world around us. At its most powerful, environmental art goes beyond simply depicting nature—it intervenes, reimagines, and compels us to reassess our relationship with it.

CULTURED invited a range of artists whose work engages with the nature and environment—including Anicka Yi, Sarah Meyohas, Wendy Red Star, and Alexis Rockman—to reflect on the most influential work of environmental art of the 20th and 21st centuries so far. Their selections span speculative ecosystems, light-based installations, and regenerative landworks. Some of the works chosen are poetic, others prophetic—and all have lingered in the minds of the artists who selected them.

Taken together, they offer something urgent and enduring: a call to pay attention, to live with greater intention, and to believe that even in apocalyptic times, beauty and imagination can still take root.

Wendy Red Star

Rebecca Belmore, Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother, 1991

“I first encountered Rebecca Belmore’s Speaking to Their Mother in graduate school at UCLA in 2006, and it has stayed with me ever since. As a work of environmental and land-based art, it stood out because it centered Indigenous presence and sovereignty through poetic and political means. The sculpture’s form—a massive, hand-crafted wooden megaphone—was powerful not only in scale, but in purpose. It wasn’t a tool for projecting one voice, but for inviting many, especially those from communities often unheard, to speak directly to the land.

What struck me most was the intimacy and mobility of the piece. Belmore traveled with the work, sleeping beside it in her van, bringing it to reserves and sacred places. That act—inviting people to speak their truths in their own languages, addressing the earth rather than institutions—felt revolutionary. It shifted the idea of audience and transformed protest into ceremony.

As an Apsáalooke artist, this work shaped my thinking around how objects hold presence, history, and collective voice. It affirmed that art can move through time, place, and community, grounded in care and responsibility. Speaking to Their Mother continues to influence how I think about land, legacy, and the power of ancestral dialogue in contemporary practice.”

Anicka Yi

Helen and Newton Harrison, Shrimp Farm, Survival Piece #2, 1971

“I first encountered Helen and Newton Harrison’s Survival Piece #2: Shrimp Farm while researching for my ongoing book project Tumbling Ecologies—a trilogy exploring new modes of existence through the lives of algae, bacteria, and fungi. What struck me was how radically prescient the work feels today. It’s not simply art-as-warning; it’s art-as-prototype—a living system calibrated for survival in an era of ecological precarity.

The Harrisons translated the logics of minimalism and color field painting into a fully functioning ecosystem—a poetic engineering of algae, brine, and shrimp that pulses with both formal restraint and biological urgency. It’s a gesture of care and cunning, and it continues to resonate as we teeter on the edge of cascading environmental and geopolitical crises. Their work insists that art doesn’t have to merely reflect collapse—it can metabolize it, feed off it, reimagine our thresholds for survival. I often return to Shrimp Farm when thinking about how systems of life—even at the microbial level—might also be systems of resistance.”

Arlene Shechet

Andrea Zittel, A-Z West, founded in 2000

“I find Andrea Zittel’s long-term project A-Z West and High Desert Test Sites to be a radical and deeply moving structure that I think of as environmental art at its best. In seeking a new model for living a good life (in an extreme desert environment) and developing a hands-on practice of making everything (with ingenuity and panache) and then sharing all of it, Zittel has put her life and theory in one inspiring package. I also love that now, after 25 years, she is evolving the model by hiring a director!”

Mary Miss

Mary Mattingly, Swale, 2016; Katie Holten, Tree Museum, 2009-2010; George Trakas, Newtown Creek Nature Walk, 2007; and others.

“When I think of calling out the most important environmental art, I imagine a constellation of projects rather than a single one. I say constellation because in these complex times I believe it’s important to reflect on multiple projects by an array of different artists. We need examples of many works at all scales, both temporary and permanent, to build connections to the natural world and the systems that support our lives.

Projects that come to mind are Mary Mattingly’s barge called Swale that moved around different locations in New York City’s harbor, and Katie Holton’s Tree Museum in the Bronx. I think of composer Kamala Sankaram’s work that you can listen to as you walk the path of a buried stream or Matthew Lopez-Jensen and Ana De la Cueva’s 15-foot crowdsourced tapestry made up of over 100 squares. It helps people imagine what it would be like to have an urban neighborhood filled with green roofs and streets. Or George Trakas’s walkway at the water’s edge of Newtown Creek that creates a visceral connection to the adjacent water treatment facility. All of these artists produce distinct and compelling experiences that can help to build a widely embraced culture of care and connection to the natural world.”

Sarah Meyohas

Rei Naito and Ryue Nishizawa, Teshima Art Museum, 2010; Sarah Meyohas, Truth Arrives in Slanted Beams, 2021

“When I visited the Teshima Art Museum [in Tonosho, Japan], it was raining—hard. The structure, shaped like a droplet held in suspension, didn’t resist the weather. Rain fell through two large oval openings. The white of it held everything—the light, the sound, the passing time. Rain hitting concrete. Then—quietly—movement.

Water emerges from tiny holes in the floor—softly, without announcement. Some come from the rain, some from a well beneath the museum. They merge with others, grow larger, and slide across the concrete in slow rivulets, guided by the floor’s barely perceptible slope, by gravity, by surface tension.

It showed me that a structure built at the scale of architecture, but conceived as art, can recalibrate perception. That nature—weather, water, time—can move through a work. That an artwork can hold multiple scales at once: the vast curve of concrete, the minute pull of a droplet. And in doing so, make you newly aware of your own scale within it. Those ideas lingered—quietly, structurally—until they reemerged more than a decade later in my first outdoor work.

For Desert X, I built a white ribbon of wall, eight feet wide and four hundred feet long, rising and dipping across the desert floor—massive in scale, architectural in its construction. Within each curve, I placed a series of reflectors—precision-milled to shape sunlight into caustic patterns. Caustics are everywhere—at the bottom of a pool, across a glass of water—usually accidental, but here, made deliberate.

In this installation, the caustics weren’t just flickers of light or abstract forms. They were language, literal words appearing on the wall. To do this, every variable was precisely computed: the path of the sun, the ribbon’s orientation and curvature, the distance between each reflector and the wall, and the exact geometry of the reflectors themselves.

This installation is an instrument for light. It captures, bends, and redirects the sun’s rays, revealing something hidden—an ephemeral message that only exists in the meeting of light and surface. The phrase it casts—'Truth arrives in slanted beams'—is not simply written; it emerges the way all truth does, through position, perspective, and time.”

Maru Garcia

Lauren Bon's Metabolic Studio

“Lauren Bon and her practice, Metabolic Studio, have profoundly influenced my work. From iconic pieces like Not a Cornfield and Bending the River, to The Smallest Sea with the Largest Heart, the necessity to find ways to 'create at the same capacity that society has to destroy' is a vital call for artists engaged in environmental topics. I particularly share with Lauren our love for soil, as demonstrated in Un-development 1, which seeks to turn a tow yard back into a floodplain, Un-development 2, which aims to build a riverbed inside an industrial warehouse, and a recent piece titled Moving Mountains, which saves landslide soil and creates connected micro-forests. All these exemplify the application of regenerative practices, natural remediation, and a new way to think about art that makes change possible.”

Alexis Rockman

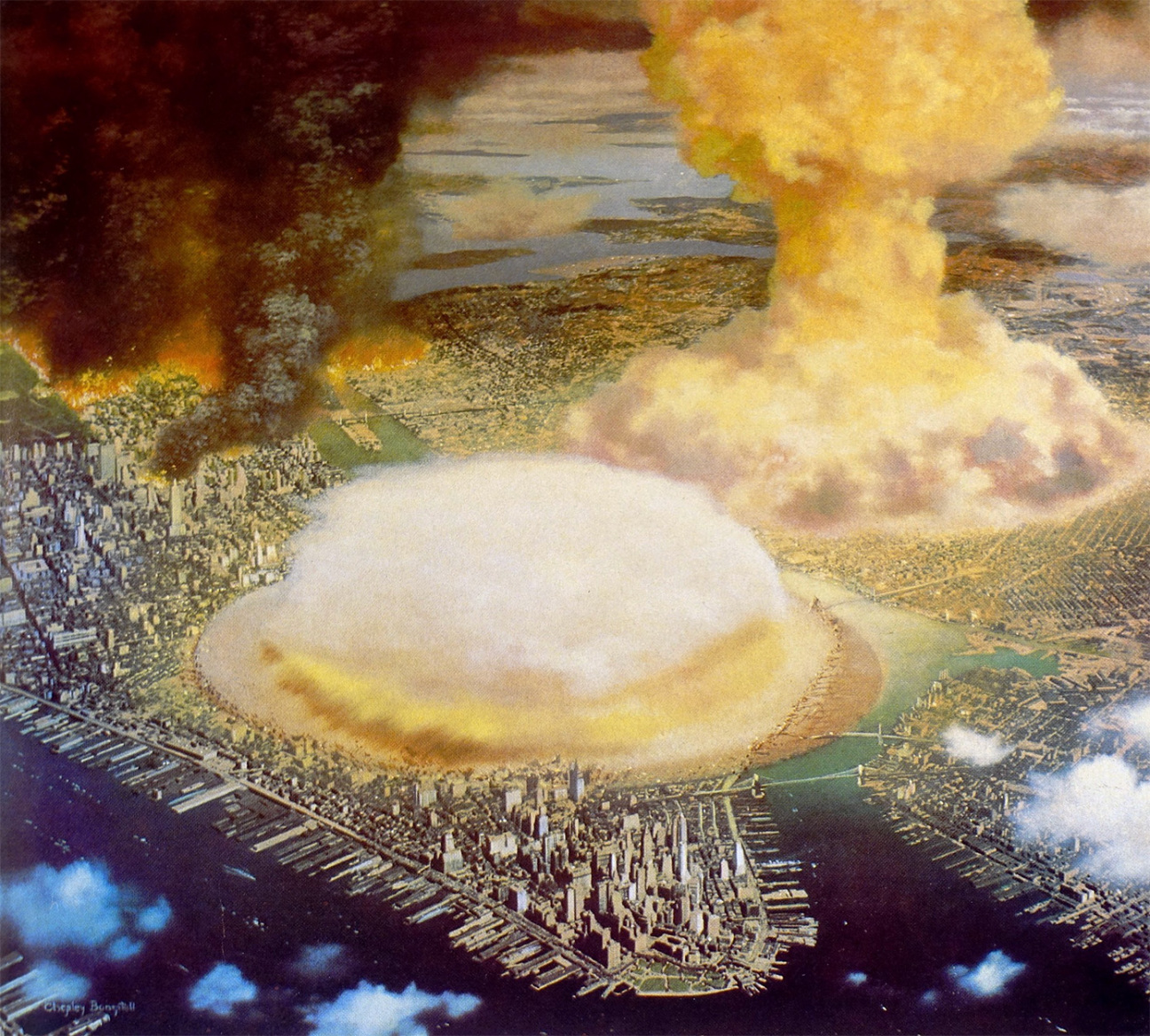

Chesley Bonestell, Atomic Bombing of New York, 1948

“In 1996, when I was trying to figure out how to depict the coming terrors of global warming, I thought of Chesley Bonestell’s cycle of paintings of nuclear bombs exploding over the world’s great cities made during the Cold War for Collier's Magazine. Bonestell made several about New York, the place I grew up, and I saw them for the first time in the late 1970s. Forensic and terrifying, these images showed me in detail the specifics of what would happen to the neighborhood I grew up in Manhattan if we were under a nuclear attack. They hit me like a punch in the gut. The shocking juxtaposition of familiar geography with inconceivably catastrophic iconography seemed like the perfect balance to sound the alarm for impending challenges like sea level rise for paintings of mine like Manifest Destiny, 2004. Of course, this iconographic strategy has a long tradition, ranging from Pompeii and the Romantic impulse to Thomas Cole and Planet of the Apes.”

Paul Anthony Smith

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Surrounded Islands, 1980-83

“I first encountered the work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude in my 6th grade art class in Miami. I was captivated by Christo’s drawings, and my interest in the magnificent scale of their work grew while visiting the Pérez Art Museum and seeing the renderings of Surrounded Islands. The drawings and the subject matter interest me because there is a collage aspect, which comes to life in a scale that pushes the boundary of what art and environment become together, and I was born on an island, Jamaica. In Surrounded Islands, Christo and Jeanne-Claude literally cover the perimeter of an archipelago of islands in Biscayne Bay with thousands of yards of pink fabric simultaneously blocking and protecting them. Covering, protection, and masking are all themes that I explore heavily in my work. some of my works are covered with veils of beads often found in Caribbean homes and they both conceal and protect the location and identity of the subject. I’d also like to think that one day I could pull off a project in the environment as large and dreamlike as Christo and Jeanne-Claude.”

Diana Thater

Crested Macaque Monkey, Selfie, 2011

“This might not be environmental art, but it is an astounding image of the living environment, and it does what 'environmental' art should do and that is to give us an appreciation of the fascinating lives of others. It covers the 'art' part of the equation be being a REALLY GOOD photograph—something, ironically enough, we see very little of these days.

The story is this: A photographer was filming crested black macaques in Indonesia. He left his camera, and a female macaque snapped a series of self-portraits. You can see her thinking about it across the range of images. There are several shots where she tries serious looks—then she finally grins. Presumably, she was looking at her own reflection in the lens as she tried out different attitudes. In some of the photos you can see the camera lens reflected in her eyes. It’s not just a charming image of self-reflection; smiling from ear to ear, this macaque presents herself to the world. My purpose in making art is in representing those who do not represent themselves. But this macaque doesn’t need me. Crested black macaques are critically endangered.”

in your life?

in your life?