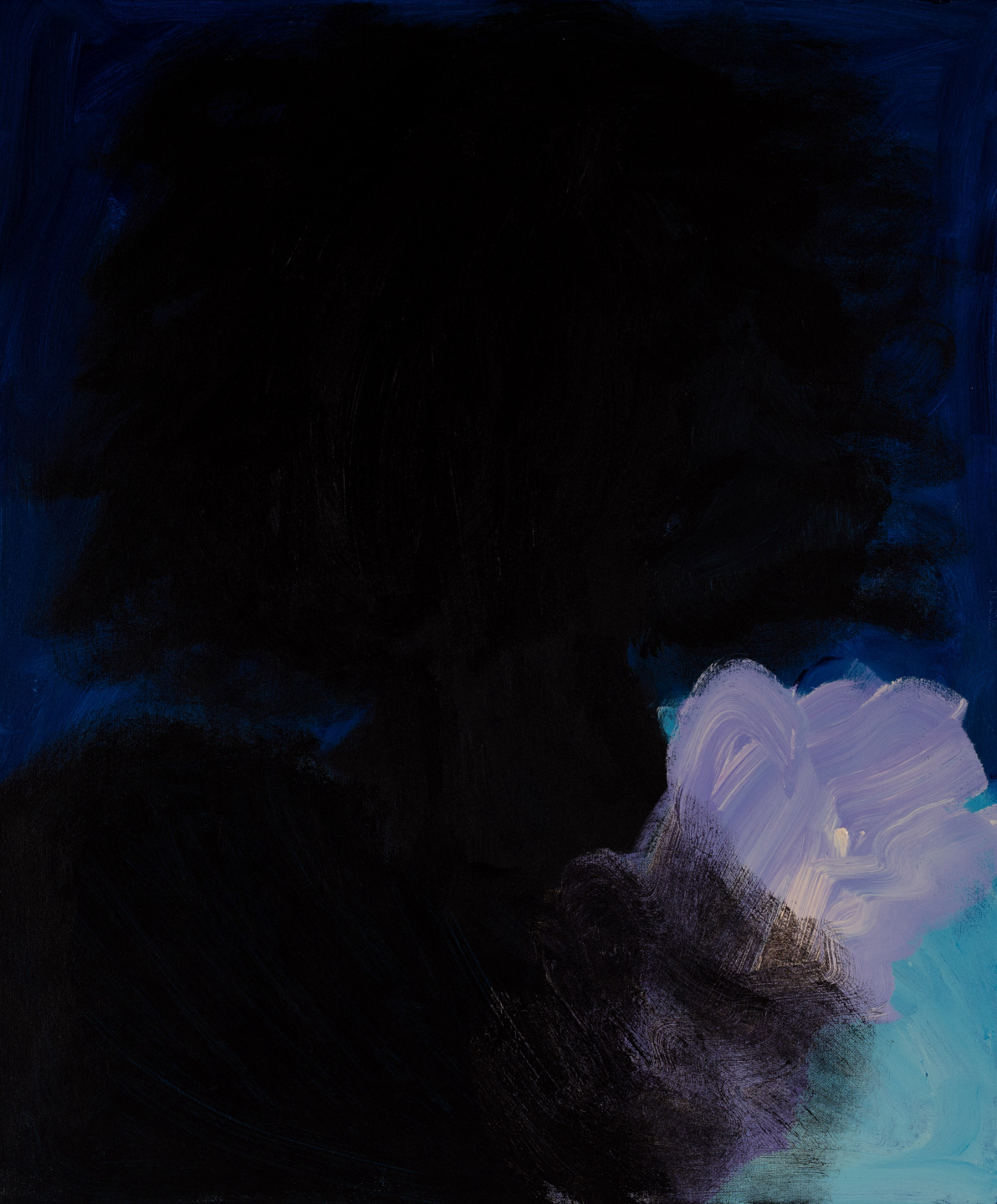

Hovering between abstraction and figuration, Ruth Ige’s paintings are adrift with color. Bodies swim in the murky fields of the imagination: blue, black, and white rendered with urgent, gestural strokes that blur distinctions between figure and ground. Described with shadowy black paint that recedes in and out of visibility, these figures are featureless, their Blackness baring a hauntingly assertive presence on the canvas.

After a solo exhibition earlier this year at Roberts Projects in Los Angeles, the Nigerian-born, New Zealand-based painter has unveiled 12 new paintings at Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg. Ige has long been invested in a complicating and expanding the way Blackness is represented in figuration, a commitment which resurfaces in the ethereal yet brooding passages of black paint of the new series, which articulates Blackness with an otherworldly fluidity. Her approach to the Black figure is suffuse with what she describes as a “meditative atmosphere of mystery”—a defiant illegibility.

The works on view in “Freedom’s Recurring Dream” are premised on the idea of a personified freedom, an embodied yet elusive entity who is described in a text accompanying the exhibition as appearing “in a place between two dimensions.” For people of the Black diaspora, freedom can feel like an intangible dream, one that has long been deferred, but Ige flips the script, giving Freedom herself the capacity to dream and meet figures in the thick of her nighttime imaginings. “The paintings are through her eyes and perspective,” says the artist. “The figures in my painting are fictional… freedom is a mothering figure to them.”

Freedom’s dreamworld, as envisioned by Ige, is layered—bristling with possibility and hope, it is also textured with longing and melancholy. The paintings are awash with this tension: their gestural brushstrokes are simultaneously bursting with freedom and fraught with anxiety. For Ige, color is also a key device in setting the tone. Her paintings brood with a blue moodiness that has grounded Ige’s entire body of work, and for the artist it is “a form of language,” she explains. “It can convey sadness, but also renewal and hope at the same time. It can be otherworldly, but also familiar.”

Springing from the deep well of Ige’s imagination, the exhibition takes many of its cues from Black speculative fiction. As a child, Ige wanted to be a writer, awed by the fabular potential of language. “I have always carried that sense of imagination with me to adulthood,” reveals the artist, who craves heightened attention to Blackness in discussions on science and speculative fiction. Untethered from a place or time we can locate, the paintings at Stevenson Gallery carry this enthusiasm for future possibility, conjuring up dreamworlds that are elsewhere. They dare to wonder what it might look like if freedom were a caretaker for and mother of Black people. Titles like A gift (to weather the storm) and Songstress (both 2022) allude to this speculative time, suggesting something that is impending rather than now. But for Ige, the distinctions between these temporal categories are blurry and unfixed, meshed in the tangle of her brushwork. “I want there to be a conversation between the past, present, and future,” she says. “I am not just focused on the future—I am still anchored to history and grounded in the present. I want to explore Blackness within all these time frames.”

In Ige’s liquid compositions, Freedom’s dreams are beautifully nebulous. They come to us with tender slowness, stretching across many tenses of being and becoming.

in your life?

in your life?