On the road from Vienna to Prinzendorf Castle, the rural Austrian estate where the late artist Hermann Nitsch lived and worked, fields of sunflowers hung their heads, ominously recoiling under the gray, rainy sky. I was on my way to see The Six Day Play, Nitsch’s epic and notoriously gory 1998 performance art piece, and already felt the gnawing anxiety of watching a horror movie. At the castle, I was first struck by the sound: the 100-person orchestra in the courtyard had settled into the kind of low, sinister frequency that sinks the body with dread. The smell of burning incense followed, presaging a gruesome simulation. (If you’re squeamish or prone to nightmares, this is your warning to stop reading now). As a single performer stood blindfolded, tied to a cross, men and women dressed in identically pristine white T-shirts, pants, and sneakers went through the motions of ritual human sacrifice. They reached shoulder-deep into a pig carcass and manically rummaged around the entrails stuffed inside, coating themselves with actual blood. I stood there on an unusually cold, dark summer day in the far reaches of Lower Austria, watching a live rendition of The Holy Mountain meets Midsommar meets Anne Imhof meets Get Out.

“Nitsch himself meticulously prepared the dramaturgy, leaving nothing to chance,” said the artist’s Vienna gallerist Lisa Kandlhofer, referring to The Six Day Play’s 1,595-page score. It was his 100th action and magnum opus, a Gesamtkunstwerk involving dozens of musicians, composers, performers, and cooks. The Nitsch Foundation presented the play’s first two days on the last weekend in July, partially fulfilling the artist’s longtime wish of restaging it.

I knew what I was getting into. Nitsch, who died in April at age 83, was one of the Viennese Actionists, a category of artists who had lived through the traumas of the Second World War. In the 1960s, they staged gruesome performances, or actions, meant to confront Austria’s postwar denial of the atrocities. In his own singular fixation on catharsis, Nitsch developed his Das Orgien Mysterien Theater to mine the subconscious for repressed emotions, staging actions that evoke Catholic rituals, the Happenings of Allan Kaprow, and the grisly performance art of Carolee Schneemann. In lieu of dialogue, the O.M. Theater deployed visceral and often revolting sights, sounds, tastes, and smells; the artist was not aiming for the intellect, but directly for the gut.

To be honest, I found the first day so gratuitous and repetitive that I left early; during curiously long stretches of nothing between actions, I stood in the rain and wondered, were six days really necessary? The second day, however, felt very different. The morning began upstairs in the castle, where barefoot performers in white smocks painted what looked like storm clouds on canvases—not with paint, but freshly sourced blood from the local slaughterhouse. In choreographed strokes, they soaked the stuff into sponges and pressed and dragged it along, intermittently throwing it out of pitchers, leaving dark purple stains. As the blood pooled around my feet, something about the sound of heavy splatter combined with the overpowering smell fomented a mix of nausea and panic in my body. Ten minutes in, I had to go, and I slunk toward the nearest open window.

I watched swiftly moving clouds cast their shadows over the Weinviertel, and on the courtyard’s dry, blood-stained grass, the conductor led both the orchestra and a handful of musicians upstairs in relentlessly soul-crushing chords. Fellow spectators were sitting at picnic tables in the sun, casually enjoying coffee and charcuterie for breakfast. Directly below the window, I could see and hear a brass marching band playing a cheerful Austrian folk song. It was a shockingly gorgeous day.

“I wanted to show how pouring, spraying and smearing and splashing of red fluid can evoke intensive sensory agitation,” Nitsch once wrote. Inspired by Jackson Pollock and his peers, his painting actions were decidedly less about the finished canvas than the reactions of his audience. Mine was an adrenalized urge to both run and to shove every performer out of my way; a fellow art critic who also left early said that she cried inexplicably until she lost track of time. But then another spectator, an art world strategist, told us something completely different—after a certain point, she said, she couldn’t smell the blood anymore, so she stayed to watch the entire 90 minutes. As the performers’ painting escalated to an ecstatic frenzy, they swept her along in an unexpected state of euphoria. When we saw her again, she was standing in line for lunch, without a single drop of blood on her clothes.

We ate Nitsch’s favorite foods—pasta salads, stews, and apple strudels—and drank bottomless spritzers of his house label wine in his vineyard. After being so thoroughly wrung out, this side of the castle provided a gentle refuge where the courtyard’s sinister smells and frequencies abruptly ceased; all we could hear was the cheerful Austrian folk band and our own frequent applause. The sun melted the cynicism that I had cultivated in the rain, changing my perception of the experience entirely. Nitsch had masterfully orchestrated each sensory detail so that the days unfolded in dramatic peaks and valleys, first plunging us into the depths of revulsion and terror, and holding us there until we were sufficiently inured. We were subsequently released into the heights of merriment, into a literal party. This was Nitsch’s nostalgic celebration of the Austrian countryside, and his written program encouraged us to drink to excess without becoming belligerent.

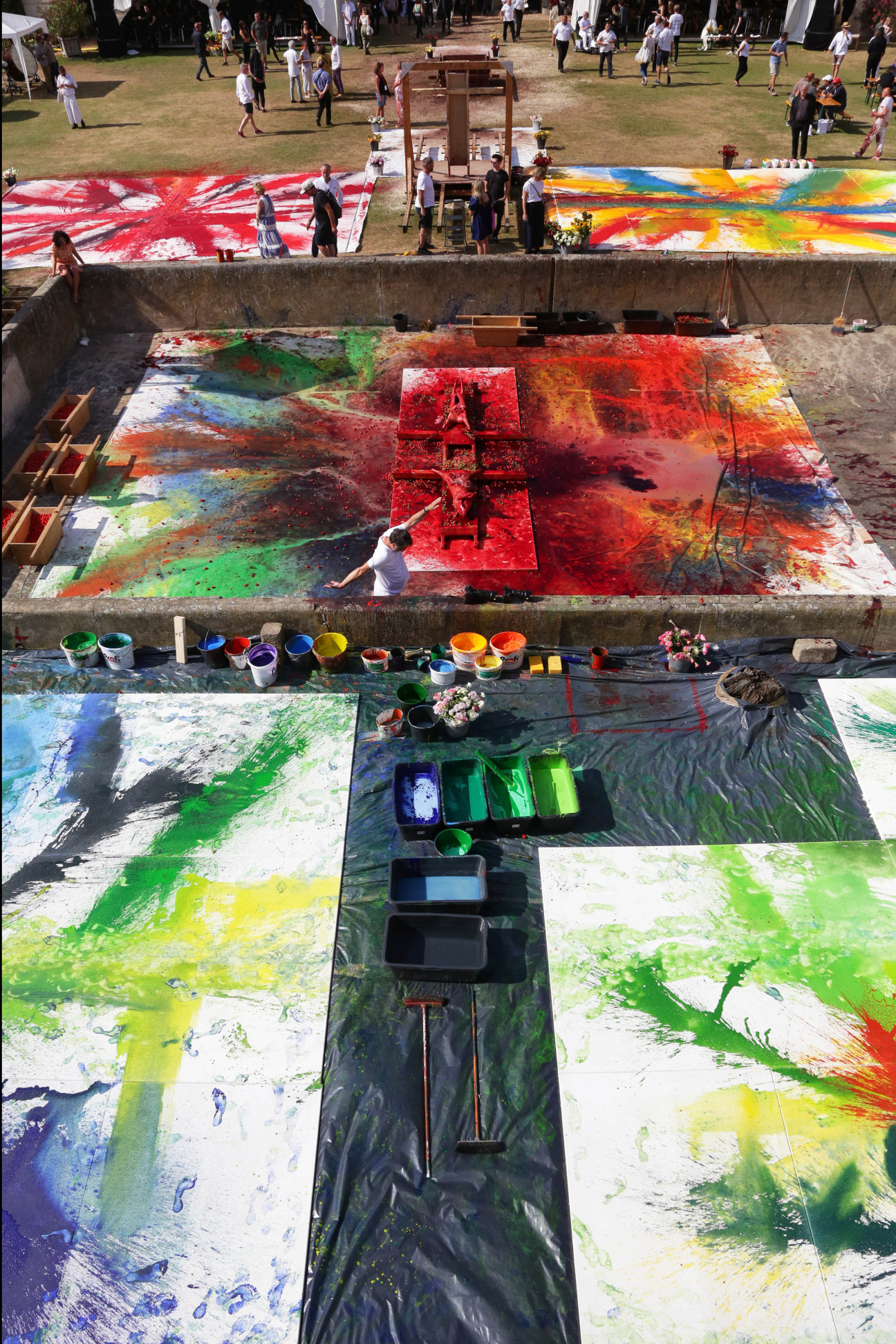

In the afternoon, when the performers lay primed canvases on the courtyard grass, they splashed them with pitchers of paint rather than blood. Some poured a full spectrum of colors down the height of an enormous white wall, creating soothing cascades that matched a mellowing of the music. The painting choreography was precise, “leaving little or no room for improvisation,” according to Nitsch Foundation artistic director Michaela Hetzel. As others walked in circles on the canvases, they lulled us and themselves into a meditative stupor. I realized then that they were neither in character, nor acting. Like us, the performers were reacting in real time, and their reactions were a contagion.

The artist’s son Leo Kopp assumed the role of director, periodically consulting a binder labeled “Day 2” and blowing a whistle to signal the start of each action. As another round of rummaging through an animal carcass began (this time with more blood, more organs, and bunches of grapes and cherry tomatoes), the music crescendoed to a frenetic pace, climaxing with the clanging of church bells. The sound roused the rummagers into an upward spiral, a competition of who could throw guts into the air the highest. It looked deranged until it looked like fun, and we arrived at a strange place where disgust and joy blur together. They cheered, and I was happy for them. I felt an enthusiastic, full-bodied excitement. I heard myself laugh out loud, which is when I started crying—heaving, ugly, face-contorted crying. I won’t spoil the ending, but the finale served the ultimate display of tenderness, a poignant metaphor for death and rebirth.

The Six Day Play is a masterfully executed, increasingly rare type of art, the kind that can never be captured by documentation, and demands all of you—often more than you’re willing to give. In exchange, the work delivers all that the artist promised: a truly visceral experience, authenticity over pretension, feeling over thinking. The actions check all the boxes of a cult assimilation, too, with the minimalist uniforms, dissolution of personal boundaries, and my newfound belief in Nitsch’s genius. There’s no doubt a fascist subtext to our passive willingness to go along, but this is the universal truth of ritual itself. Certainly Nitsch understood this; he was raised both in the Catholic Church and under Nazi occupation.

“The performance made him so happy,” the artist’s surviving wife Rita Nitsch told me. “He hoped others would find happiness in it too.”

in your life?

in your life?