In the light-filled, barn-inspired environment of the Herzog and de Meuron-designed Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York, the group show “Set It Off” presents artists who “engage the monumental, the site specific and/or the immersive.” This trio of concerns could be taken as summarizing the practice of architecture—monument, place, surround—and the work produces, within a distinctive and well-known building, its own relations of space.

Across four rooms and outdoor space, the show’s attention to each of its moments resembles a series of solo and two-person exhibits. But as a whole, it builds into a narrative that considers the experience of being situated in a body, a family and a world.

Torkwase Dyson gives a restrained account of place, expressed through formal geometrics and a subtle concern with the built environment. Her non-Euclidian studies play with different thicknesses of paint. “What new thing is there to say about the monochrome?” the paintings initially seem to ask, approaching the question from multiple black angles on the same canvas. Overlapping rectangles and slivers of white quasi-diacritic marks suggest all the ways a surface can be aware of its edge, like the way a person in a room might be always half-consciously aware of where the door is, and how to get there.

Accordingly, some of the canvases acquire architectural dimension. They are like plans or renders of future and past buildings, though they sublimate this suggestion of habitation into deep slicks of glossy black paint. In The Horizon 01 (2017) and The Horizon 02 (2017), the paintings’ awareness of space reaches beyond the rooms and to the wide outside, somewhat like the tall windows built into the gallery’s walls reveal the surrounding landscape, green-gray and whipped by occasional rain on the day I visited.

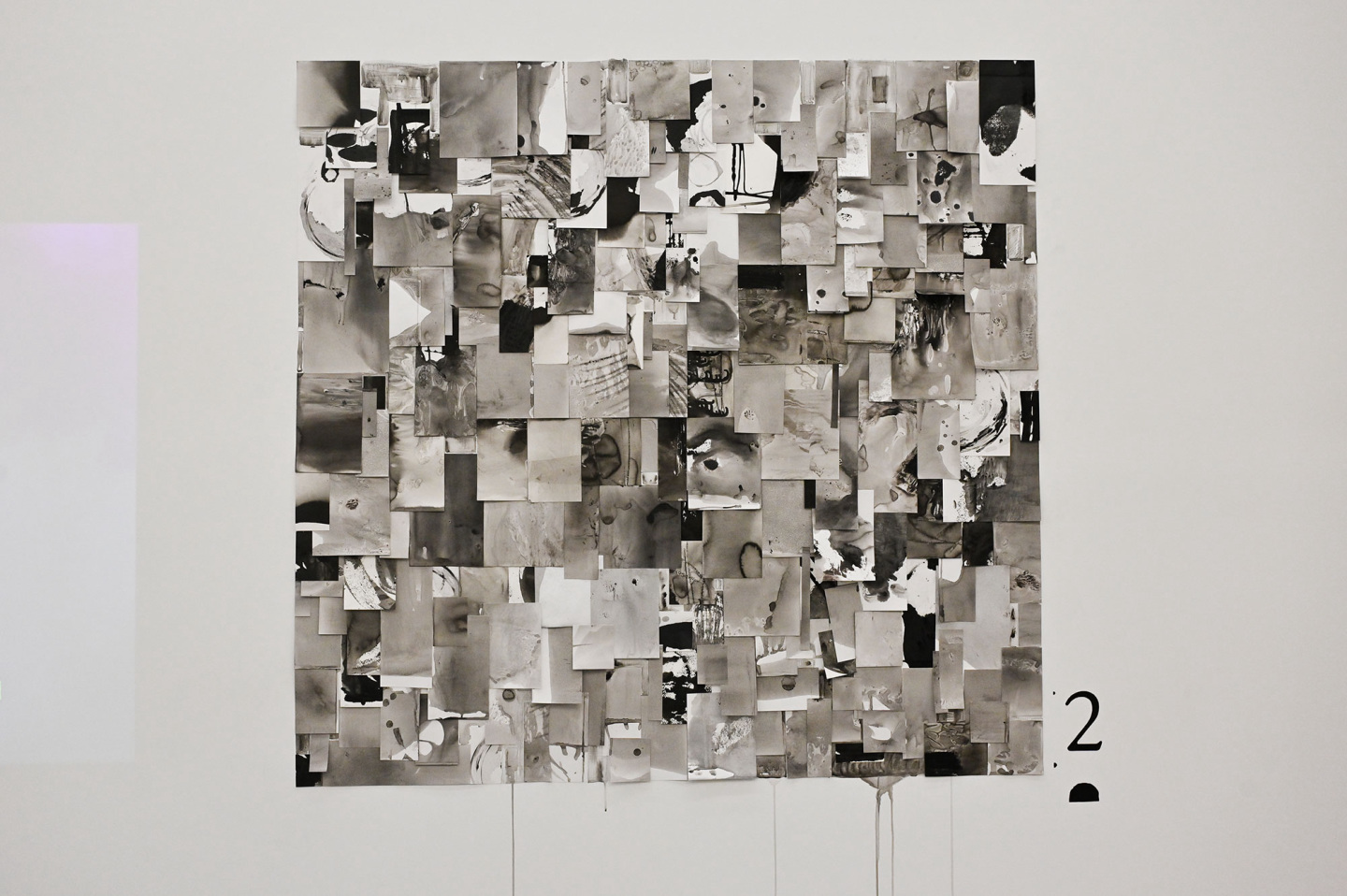

Dyson’s paintings deepen the more you look at them while across the room, Kameelah Janan Rasheed’s work also asks for long consideration to allow torn-apart fragments of language to cohere into new meaning. Perhaps in this body of work the show’s claim to the consideration of the spatial has to reach the furthest, but space here is formulated as a function of language. The diacritic—a ghostly presence in Dyson’s work—is one way to think about the role of the different elements in Rasheed’s wall-based installation, which presents a numbered progression from silent video to deconstructed painting.

The repeated phrase “I am not done yet” stenciled on the wall suggests a language with its own temporality, reformulating itself through the avatars of bodies and gestures. The silent mouth in the video enunciates something urgent and impossible; its loop is never heard and never done. The water-logged saturation of paint on overlapping fragments of paper is quite different from Dyson’s layered blacks but also evokes a navigable space. The use of pigment runs the gamut from typographic language to mute smears and drips: everything that can be done to attempt communication, though with uncertain results. Similarly, the video mouth’s teeth and tongue, multiply rendered, suggest the curious overlap of concrete and abstract, flesh and phoneme from which language is produced.

In another room, flesh is under threat where the work of Kennedy Yanko and Karyn Olivier face off and reflect upon each other. In Yanko’s monuments to the antimonumental, industrial components are crumpled, distorted and then embraced by paint skin, whose soft surface reveals less of whatever catastrophe threw them together. This is an apocalyptic aesthetics of impact whose embrace conveys the tenderness of aftermath. Suspended off the ground, the sculptures draw attention both to their materials’ weight and their unexpected lightness, vulnerability rendered ultra-concrete.

In Olivier’s work there’s also an ambivalence between embrace and threat. An asphalt substance customarily used as tar roofing engulfs or cocoons photographs of unprepossessing fragments of urban assemblages: corners of buildings with walkways on which tiny figures slouch on benches, a felled tree surrounded by drab houses, stacks of bricks with apparently discarded clothes. These images may have private significance, or they could just as easily mean nothing, but now, clasped in tar, these vignettes suggest convergences between accident and intention; tricks of sentiment, light or perception, and fleeting senses of home. In the middle of the gallery, How Many Ways Can You Disappear (2021) is a pile of ropes, traps and buoys. With tarred photographs all around me, I thought about the artist as a fisher of moments, sunk in an anonymous urban ocean. But on reading about the work, I discover that Olivier herself had cast her mind further back, thinking of the sea salt traded for slaves in Ancient Greece. Like the juxtapositions in the photographs, both strange and mundane, trade and domination produce surreal equivalences that structure everyday life.

These two pairings—Dyson and Rasheed; Yanko and Olivier—are where the thoughtful curation by Racquel Chevremont and Mickalene Thomas (Deux Femmes Noires) is most evident: the works’ placement discovers assonances that refract through each. Artists February James and Leilah Babirye are allotted a whole room each, where the tempo of the exhibition slows. Babirye’s sculptures are complex pairings in themselves. They draw together the aesthetic traditions of Kampala, Uganda, where she was born and grew up, and debris found in her current home of New York City; they unify the experience of being African and the experience of being gay; they combine traditional sculptural techniques with modern materials suggesting different forms of technical mediation. Wooden figures are enmeshed with flattened soft drink cans, wires, bike chains, clamps and bolts.

James’s paintings and sculptures teem with people: visible and invisible, self and other, alive and dead. The body of work titled These Are My Ghosts To Sit With resembles a theatrical set in which spirits perform as themselves. A wall is lined with expressive, exhausted faces in black and white, tiny canvases with thick impasto blobs of flower-like fruit. Paintings of women hang on other walls like icons of the Virgin Mary. A large-scale portrait emphasizes James’s attention to the gaze: there are yellow-tinted eyes in exaggerated closeup, imperfectly coiffed eyebrows, and a third eye lurks like an afterthought beneath a layer of paint on the brow.

More icons by James: ten striking works on paper present faces in which layers of watercolor and ink create create remarkably precisely conveyed expressions and provide the distinct contours of personality. These faces, never seen before, are deeply familiar. The room is a place for them all to hang out. The furniture seems to have grown pigmented mold, like dried ectoplasm. There’s a yellow paneled armoire with a woman haloed in its center, and an unoccupied table and two chairs at which invisible ghosts are sitting on either side of a jaunty vase of fake flowers.

Whether it’s a room, a city, a nation or a language, the self—as the deeply personal works in “Set It Off” suggest—is always inflected by its location. The task is to find ways in and out.

in your life?

in your life?