Tomashi Jackson flipped through pages of notes inscribed into a sketchbook during a virtual studio visit that took place at the height of a sweeping pandemic. She had just planned to move into fellow artists Elle Pérez and Matt Saunders’s shared Cambridge studio to develop work for a new exhibition at Harvard University’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, when large swaths of the world suddenly ground to a halt. Up until that point, Jackson’s practice had taken her on a whirlwind journey that matched her artistic fervor. In little over one year, various exhibitions and opportunities had relocated her studio from Brooklyn to Skowhegan, Richmond, Athens, Los Angeles and then, finally, Cambridge. When we first spoke at the tail end of March, the artist had been dedicating her time in quarantine to three overlapping projects—one would have been a month-long residency at Southampton’s Watermill Center, intended to culminate in a solo exhibition at the neighboring Parrish Art Museum. Since postponed to Summer 2021 and reconfigured with a series of public programs, the project, titled “The Land Claim,” seeks to address the racial and economic inequalities that persist throughout the famously privileged enclave of New York’s Eastern Long Island.

The Houston-born, LA-raised artist first set her sights on Long Island after Corinne Erni, the Parrish’s Senior Curator of ArtsReach and Special Projects, expressed interest to her gallerist, Connie Tilton, in 2016. Soon after meeting one another, Erni invited Jackson to mount a solo exhibition within the museum’s light-filled expanse, upon which the artist took up an immediate interest in the Hamptons’s political and social dynamics. Having little prior knowledge about the region, she initiated a deep dive into the history and contemporary realities of a locality that has long been regarded as a geographic status symbol for the well-heeled elite. Through conversations with people who lived in the area, Jackson quickly became aware of ICE checkpoints and raids, which brought to her mind similar occurrences of violent oppression in the past. Of these exchanges, she recalled, “I closed my eyes and started thinking about Alfredo Jaar’s descriptions of secret police snatching people off the streets in Chile, of the Panthers being kidnapped in Oakland and Houston. I saw, in my mind’s eyes, scenes of Black children being twisted into pretzels by full-grown, white police officers; images of Black people being attacked by police dogs and hit with water cannons.”

In keeping with these methodologies, Jackson travelled to Long Island at the end of January to conduct oral interviews with key individuals whose stories shine a light on communities that one seldom hears about. These figures include Minerva Perez and Bonnie Michelle Cannon, the executive directors of two important local non-profits that provide resources for Latinx immigrants and seasonal workers; Kelly Dennis, a Shinnecock tribe member who previously worked at the Watermill Center and is now an attorney specializing in Federal American Indian law; Georgette Grier-Key, who helms Sag Harbor’s Eastville Community Historical Society; and Richard “Junie” Wingfield, a descendant of a Black family that migrated from the Carolinas to Long Island during the 1800s. Although Jackson was not acquainted with these people prior to her research, she spoke of them with an intuitive sense of compassion for their histories and respective causes. Even over Zoom, the artist’s warmth and knack for listening felt striking.

Guided by meticulous research, Jackson has long been concerned with, in her words, the “global history of abuses of power.” For her concurrent solo exhibition at Jack Tilton Gallery and presentation at the Whitney Biennial during the spring of 2019, she created large compositions that delved into the displacement of Black homeowners in a neighborhood once known as Seneca Village; in a bid for urban renewal during the 1850s, the area was razed by city officials to make room for Central Park. These projects were soon followed by an exhibition that opened at LA’s Night Gallery in January of this year, which featured works that bonded the crack epidemic of the 1980s and the suppression of Black votes in America. Combining recent election ephemera with images of figures such as Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, these compositions placed democratic ideals in dialogue with the painful realities of systemic inequality. Such bodies of work not only projected Jackson’s anxieties about the ramifications of white hegemonic power, but also made bold visual statements for a thoughtfully developed style.

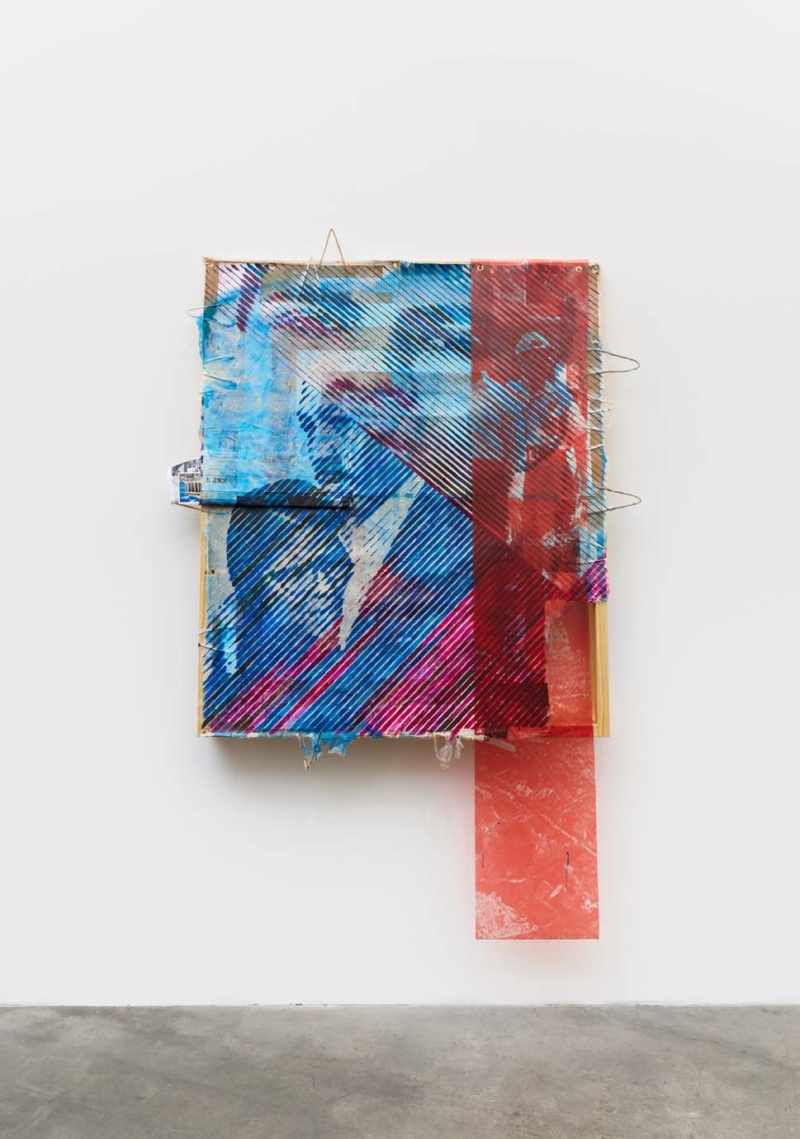

Early on in her MFA program at the Yale School of Art, Jackson was reintroduced to Josef Albers’s Interaction of Color (1963), which provided the basis for a new understanding of color as a mutable, subjective entity. According to the instructive text, humans’ perception of color changed depending on its chromatic context. This concept—that the inherent value of a color could not be objectively determined—deeply resonated with Jackson, who saw a conceptual link between Albers’s color theory and the systemic racism that permeated so many parts of the world. She decided to expand upon the idea, by reducing compiled photographs into halftone lines which are then rendered in vibrant hues on transparent materials such as mylar and vinyl. Layered atop one another, snapshots of individual occurrences become collapsed into larger narratives about the discrimination, exclusion and suppression that have prevailed throughout human history. While some images are starkly highlighted, others register as barely legible when confronted with other overlapping colors and patterns. By arranging visual symbols in this way, Jackson excavates our collective photographic memory and makes a compelling case for the interconnection between seemingly disparate episodes of racial and social injustice.

Reading from notes diligently taken during her interviews, Jackson relayed powerful accounts of the oppression that continues to unfold across the Hamptons. There is the incessant threat posed by ICE—disturbingly, she learned of a checkpoint set up next to an elementary school where immigrant children are known to be enrolled— in addition to the many hoops that migrant workers must jump through in order to access education, housing and public transportation. There is the seizure of Shinnecock land, which gave way for an invitation-only golf club that does not pay any property taxes and therefore further starves local schools of resources. Lastly, there is the historical exclusion of Black farmers and workers from white-dominated spaces, which has created great disparity by rendering this community “land-rich but cash-poor.” Rather than framing these accounts as isolated incidents, the artist draws connections to similar narratives across the United States. She mused, “There is no place in this country that is untouched by the historic presence of Indigenous, Black and brown people. It’s part of what makes an invitation like this—an opportunity for research—so rewarding.” Jackson sees a glimmer of hope in the way that current circumstances, dually defined by rapid digitization in the face of a pandemic and widespread outrage over the systemic racism of America, may pave the way for more inclusivity within the contemporary art world. Inspired by the new direction that her Radcliffe Institute project has taken, the artist hopes to compile audio recordings for a publicly accessible oral archive of the histories that her project strives to uncover. As of this article, the first segment had already taken place, in the form of a virtual conversation between her, Erni, Dennis and Georgetown Law professor K-Sue Park, centered on the issues surrounding land rights in the United States. Further dialogues with other research participants, as well as a publication and other pedagogical materials, will follow in the months to come. Ever resolute in her mission to shed light on “the narratives that already bear the burden of being exploited, overlooked and neglected,” Jackson marches onward.

in your life?

in your life?