Elliott Puckette isn’t afraid to make art that is beautiful. This may seem obvious at first, but for an artist that came of age during a time when painting was a dirty word and the cool kids at Cooper Union—where Puckette received her BFA in 1989—were making mostly politically charged, heavily theoretical works, it’s a subtle act of rebellion.

“I think people are still afraid of making something beautiful,” says Puckette. “There always has to be something kind of nasty or edgy about it to be taken seriously. I just don’t really subscribe to that.”

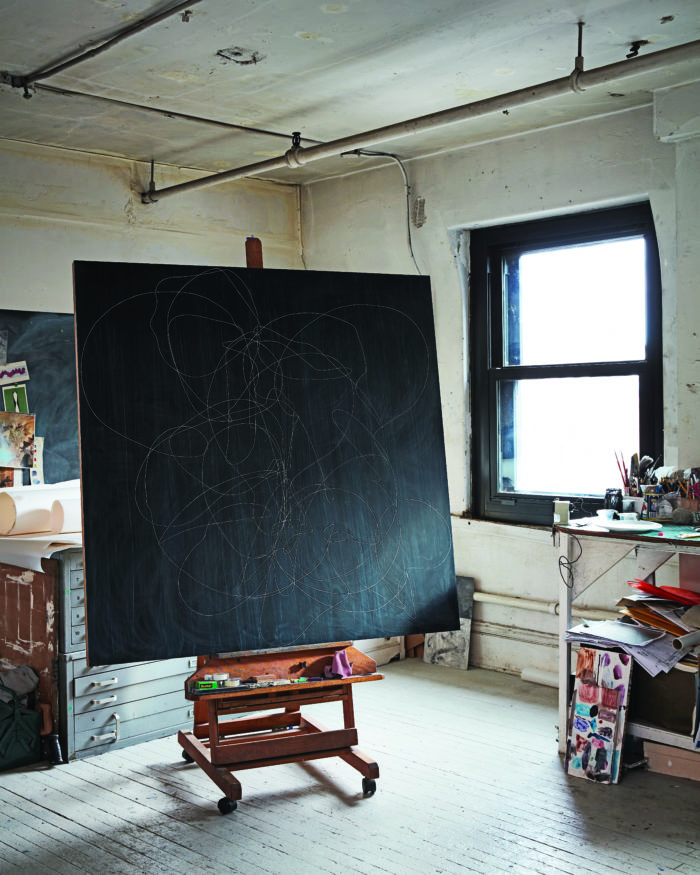

Often described using words like delicate and ethereal, Puckette’s paintings draw from the aesthetics of calligraphy and reveal an obsession with the many possibilities of the line. Her solo show at Paul Kasmin Gallery features new works created using abstract wire maquettes that she fashions herself and then translates to the canvas. The idea, says Puckette, is to lose a degree of control by forming an intermediary between herself and the paint.

“Some of them feel very fragile, like an old lady’s handwriting, sort of wobbling,” describes Puckette of the finished product.

Based in New York, Puckette has been represented by Kasmin since 1993, making her relationship with the gallery one of its longest. After arriving in the city in 1985, she met Kasmin—then a young photography dealer—through her ex-husband. She occasionally helped out at the gallery doing inventory while in art school and struck up a fast friendship with the dealer. Several years later, he saw her work and asked her to do a show.

Kasmin eventually morphed into a powerhouse dealer with a star- studded roster and three large spaces in Chelsea. Yet Edith Dicconson, a gallery director who has worked with Puckette for six years, still describes her as “one of the backbones of the gallery.”

"I think people are still afraid of making something beautiful. There always has to be something kind of nasty or edgy about it to be taken seriously. I just don’t really subscribe to that."

Dicconson is also quick to note the depth of Puckette’s artistic evolution. After years of painting abstractions that traced a single line and were, according to Puckette, “finished when the snake did its tail,” she debuted the so-called wire pictures at the gallery in 2014, marking a stark departure from her previous way of working. Whereas earlier work was heavily influenced by the free-wheeling nature of Surrealism, Puckette’s new paintings feel at once more considered and more explosive. The forms depicted on her canvases look less like snakes than intricate mazes with many possible roads and little opportunity for exit.

“It’s a huge change and shift for Elliott and how her process evolves out of herself,” says Dicconson. “It’s a big hurdle for her, and the effects have been fantastic. Her growth has been really great because of it.” While Puckette’s own artistic practice has matured, those heady years of the downtown art scene still aren’t far from her mind. In fact, she sees some of that spirit beginning to re-emerge today, despite the gentrification.

“There were these naked painted ladies going around to all these gallery openings the other night and I just thought, ‘This is so great!’ Just like it was back in the day,” she says with a laugh. “I mean, it has changed so much, but you still get these little glimmers.”

in your life?

in your life?