However, the artist takes other positions more concretely. “My friends and I were thinking a lot about New York as a center of general awesomeness, so I moved down there right after school.” In 1973, Dunham arrived at a loft on 26th Street. Life there was lonely at first, far from the more-happening Soho. “It was pretty grim back then. It was nothing like it is now. Nothing in New York is.”

Dunham worked as an assistant to artist Dorothea Rockburne, who was the subject of a MoMA retrospective in 2013. Her practice, her addressal of drawing, helped shape Dunham’s work as a painter. In the ‘80s Dunham’s paintings were chaotic, highly populated by biomorphic shapes. A lot of them looked like many paintings in one. They harkened aspects of Philip Guston—sausage-y subjects and lots of fleshy red. And they contained hints of what was to come: vaguely testicular objects, and plainly penile ones too.

“I’m very interested in this point where so-called art history, fine art tradition and one’s actual inner life rub up against each other.”

In the ‘90s his works acquired the decade’s bright neon hue, and the subjects included a lot of psychedelic, cellular-looking structures. These abstract forms gradually grew identifiable body parts. In works like Saddle Ridge (1997), there’s a motley crew of rectangular creatures with phalluses protruding from their foreheads. They’re hanging out on an apocalyptically dirty, two-cheeked hill.

These works brought to mind teenaged boys doodling in class. “That’s a pretty accurate description of my anatomical capabilities,” Dunham quipped. “I actually remember those kinds of doodles and trying to figure out a reductive glyph for female genitals and things like that. I don’t remember what those things look like, but I remember the impulse.”

To be clear, Dunham is not totally consumed with lascivious subjects. His early 2000s work contained a lot of geometric abstraction that seemed under a microscope, and many paintings took on a noirish twist in the years after 9/11. But his vulgarized works have drawn the most attention. In one painting, called Square Mule (2006), a figure in a suit and top hat has what looks like a gun inserted into its ass. Viewed from a floor perspective, the other formal focus of the painting is the vagina.

Dunham received both criticism and praise for his Bathers series, done around 2012, which portrayed women wading in lakes, amongst trees under blue skies. Their breasts and vaginas are graphically attention-grabbing, swollen visual pivots. Some interpreted these works as fetishistic and blazingly reflective of the male gaze, but Dunham insists that he is not sexualizing his subjects. He says it’s much more about the fact that “everyone has a mother than it is anything having to do with sex or prurient interest.”

It’s difficult to make any claims about the artist’s intention. It’s easier, however, to take Dunham to task for this exclusionary statement on those critiquing him: “They just feel like they’re points made by people who are so stuck in our immediate cultural moment and so unable to think more broadly about the so-called human condition that they aren’t even worth listening to in a way.”

Dunham makes a valid point when he says that “there are other things about naked women than them being sex objects,” but part of the immediate cultural moment—the one he dismissed as lesser than the grand existential project—is understanding one’s own complicity in larger structures of patriarchy, no matter how feminist they consider themselves to be.

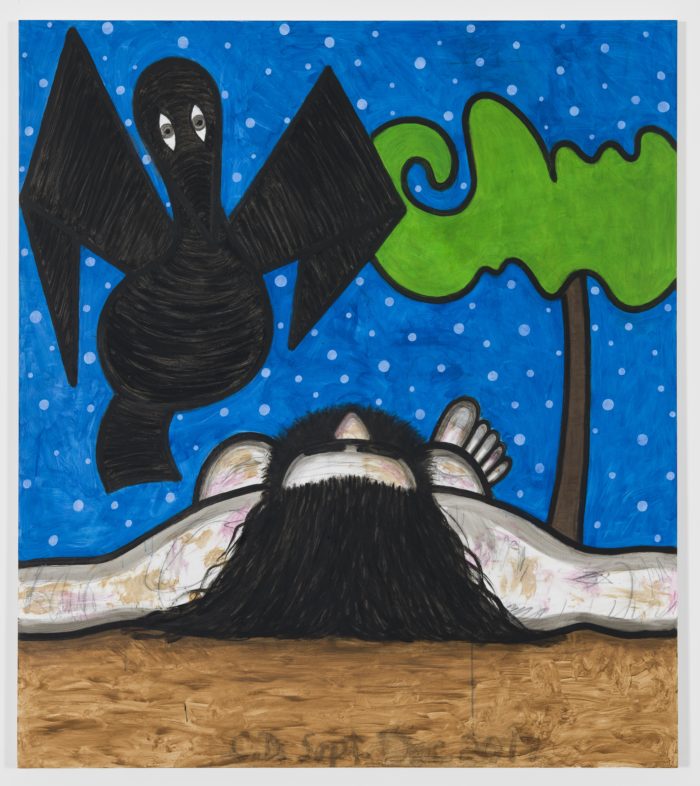

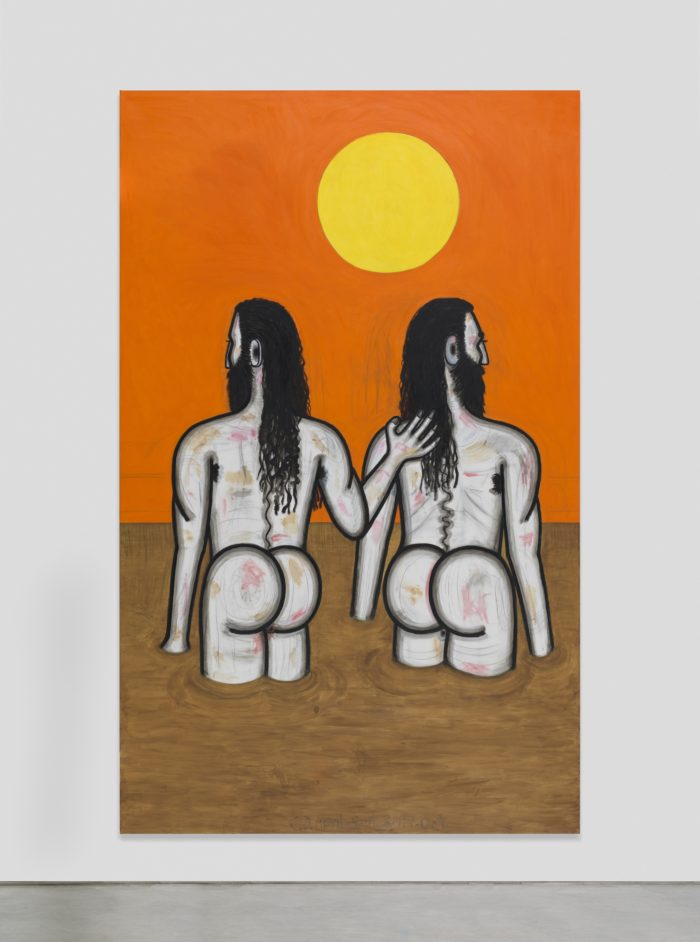

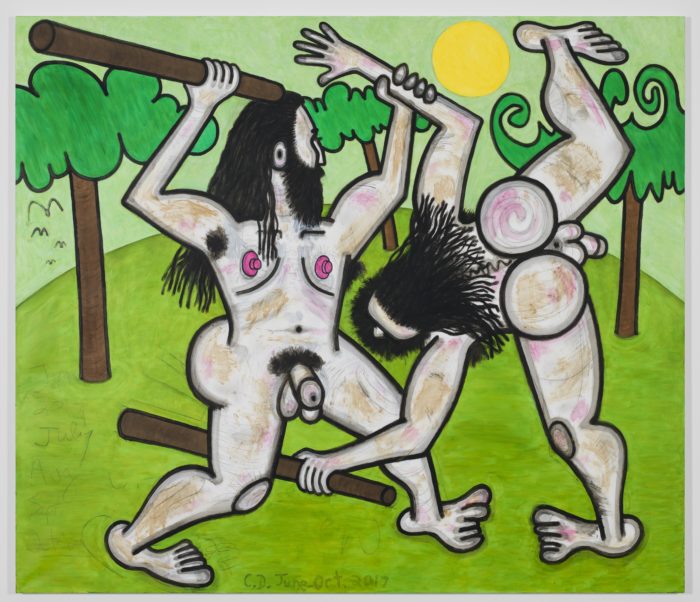

Half of the new works to be shown at the Gladstone Gallery are images of nude men laying around, blackbirds hovering overhead. The other half contains men sparring with clubs, wrestling and grappling. “I liked the way it’s kind of right in between playing and trying to kill each other,” Dunham notes. As for the switch from female to male forms, he acknowledges that the current discourse around gender inequality and violence may have nudged him.

Though he makes his pro-woman stance very clear, he also reveals a certain tone-deafness to the woke politics of privilege. “I wanted things to be more complex, and I guess I felt ready to inject my own maleness into my paintings again, as more of an overt subject,” he explains. “It’s a weird time to be a white man.” A foot-in-mouth moment, perhaps, but it also speaks to a genuine cultural crisis of identity.

During our lively discussion, Dunham mentions his addiction to television. In the search for influences on his work, we may have stumbled onto something. “The idea of episodic narrative structure with a shared world, one that continues to be elaborated, is fascinating to me. That feels very close to how I feel about my artwork at this point in my life.”

Even though Dunham is tired of connecting his personal life to his work, he acknowledges that, maybe, there are depths yet to be plumbed. “I’m very interested in this point where so-called art history, fine art tradition and one’s actual inner life rub up against each other.”

in your life?

in your life?