The opening of “A World in the Making: The Shakers,” at the Institute of Contemporary Art, in Philadelphia, closely follows the theatrical release of the feature film The Testament of Ann Lee, starring Amanda Seyfried. Blakey Bessire excavates how the hand craft traditions and devotional practices of the Shakers do—and do not—resonate in our own digital age.

“A World in the Making: The Shakers”

ICA Philadelphia | 118 South 36th Street, Philadelphia, PA

Through August 9, 2026

Last week I was served ads for “sustainable fly tying” and a digital “improv quilting” workshop—a small data point in a broader return to handicraft and renewed attention to skill sharing. There’s an urge to build things together right now, but we’re trapped in the singular, online performance of it. Against this backdrop, “A World in the Making: The Shakers” at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia arrives less as historical survey than contemporary interface. The exhibition sets up a relay between Shaker material culture and seven contemporary artists’ interdisciplinary work, asking what happens when communal structures are encountered through objects, archives, and bodies.

Here, calm translates most easily while discipline, belief, and labor resurface more unevenly. How does this interest in traditional handmaking sit within the sticky Venn diagram of the trad wife, the MAHA mom, and the curation of the homemade for public consumption or aspiration? Viewed today, craft starts to feel like a lifestyle signal rather than a shared practice. Are craft aesthetics stepping in where collective futures have stalled, offering atomized consolations in place of structural communality and holistic skill sharing? For the Shakers, “the world” was all that existed outside of their pacifist communal living structures. The appetite for Shaker-dom feels consonant with this idea of the collective or lack thereof today. In “A World in the Making: The Shakers,” that tension shows up most clearly in the contemporary works themselves, where Shaker belief is reactivated not as atmosphere but as language, gesture, and form.

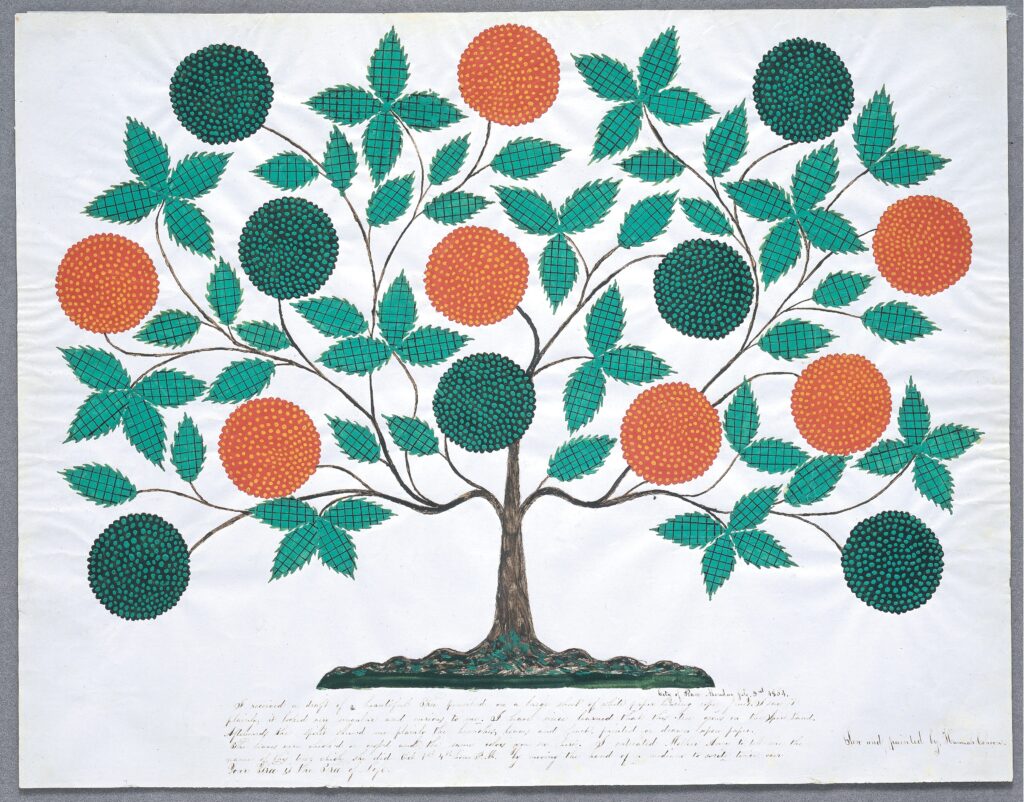

Among the contemporary artists in the exhibition, I was most drawn to Kameelah Janan Rasheed’s three newly commissioned pieces. Together, they respond to Shaker design and faith through the archive of the probably queer Rebecca Cox Jackson, who created the first Black Shaker community in Philadelphia in 1858. Rasheed carries Jackson’s language forward as a communal practice, intervening in the Shaker archive rather than citing it. Two bright white cotton sateen scrolls drape from the wall, with detailed hand embroidery in blue silk thread from the last silk-producing factory in Philadelphia. Rasheed abstracts Jackson’s spiritual texts into glyphs, echoing the techniques of traditional Shaker women’s gift drawings—depictions of personal visions exchanged with fellow Shakers, rendered with geometric precision, symmetry and bold color palettes that could rival Hilma af Klint’s.

On Rasheed’s scrolls, the original words are no longer legible, accessible only through their new shapes and the works’ titles: And at the time I was told to gather home … the time had come for me to gather home (Rebecca Cox Jackson, 237); Under it, and spread about one yard around … It was all I seen. (Rebecca Cox Jackson, 99). In afar, a black-and-white collaged video piece, Rasheed layers Jackson’s, Roland Barthes’s and the artist’s own words with Shaker imagery—hands isolated in a connecting circle, colors inverted from white to black and back again: “I left home and arrived without origin”; “I found myself in the distance—blurry.”

If Rasheed’s work pulls belief through text and archive, Reggie Wilson’s dance piece, POWER – Every Movement is Sacred, a video installation based on a 2022 performance, brings it back to the body. Working with his Fist and Heel Performance Group, Wilson treats Shaker movement not as historical object but as living structure. It’s one of the few moments in the exhibition where communal life feels present tense, not archival—where Shaker-ness registers as something practiced rather than displayed. The choreography draws on Shaker forms and shout traditions from Black churches across the African American diaspora. Here, movement is both choreographed and devotional, reflecting on how embodied practices shape identity and community, and on the legacy of Rebecca Cox Jackson within Black Shaker tradition. To the right of the video are adjacent doorways, representing the organized movement of the two genders the Shakers believed in.

Shaker objects bring with them a gradient of legibility, and their uses were allowed to shift and change. But a power lies in tying this back together with the reality of their bureaucratic mysticism. The systems and structures that narrate the function of the objects: the ledgers, the choreographies, the proto data-visualization of gift drawings, the instructional clarity with which bodies were guided through space. For the Shakers, use value was allowed to shift and change without transgression. Labor followed community need. A sewing machine becomes a root cutter. A rocking chair becomes a functional wheelchair. Inclusion is a theme in both the Shaker objects and the contemporary works throughout “A World in the Making,” appearing again with an “elevator” shoe made by Shakers in Canterbury, New Hampshire, in 1890. The platform boot was developed for a community member with legs of different lengths, a personalized response to disability made uniquely for its owner.

Seeing “A World in the Making,” I felt like I was being asked to use the Shakers as a vessel for imagining community through intentional aesthetics. But what kept coming up for me are the shadows of institutional and supremacist structures that dictate daily life; fascist structures that create their own architectures and organizations of bodies and spaces. Maybe the darkness of our political reality, and the chaos just outside any museum’s door, is exactly what the show is pushing us to counter rather than the assembled formal beauty it shows—to investigate the power of a personal (and collective) belief system, whatever that might be. The exhibition doesn’t romanticize Shaker life but thematically points to expressions of faith channeled through everyday communal acts.

I want to think this is part of what’s brought Shaker culture into the collective conscience (The Testament of Ann Lee movie’s release early this year, and the upcoming $30-million construction of the Shaker Museum’s campus in Chatham, New York, for example). The beauty of the objects is just the surface. Their resonance comes from that tug of belief. Said the Shaker eldress Sister R. Mildred Barker, “I don’t want to be remembered as a chair.”

Blakey Bessire is a writer, artist and teacher based in New York. They are an editor of the literary annual NOON, a contributing critic to CULTURED’s The Critics’ Table and the creative director of the New York Sign Museum. Their novel, Nula, written in collaboration with Irena Haiduk, was published in 2025 by the Swiss Institute.

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

Tessa Thompson Took Two Years Out of the Spotlight. This Winter, She’s Back With a Vengeance.

On the Ground at Art Basel Qatar: 84 Booths, a Sprinkle of Sales, and One Place to Drink

How to Nail Your Wellness Routine, According to American Ballet Theater Dancers

10 of New York’s Best-Dressed Residents Offer the Ultimate Guide to Shopping Vintage in the City

Sign up for our newsletter here to get these stories direct to your inbox.

[INSERT_A

in your life?

in your life?