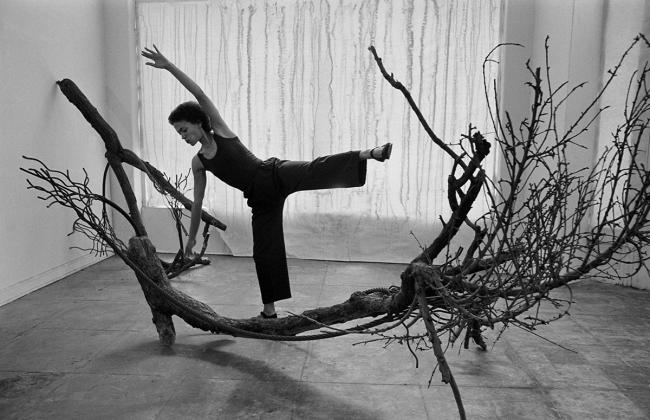

Steel is strong enough to reinforce a building, yet delicate enough to form a scalpel. In the artist Maren Hassinger’s work, the material adopts both of those qualities, but mostly it is alive. Over the years, her sculptural interventions have been activated by the elements, time, and bodies (namely her own and that of Senga Nengudi, her fellow artist and co-conspirator since the ’70s). The 78-year-old’s largest retrospective to date opens at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in June. Ahead of that occasion, we called her up to discuss her feelings about public art, what an early rejection taught her, and why she never became a starving artist.

What are you sitting with these days in the studio?

I’ve been making these vessels; most of them are middle-sized jars and bowls, and now they’re starting to get much larger. They’re supposed to still be able to be recognized as vessels, but they might be floor to ceiling. And why I’m making vessels, I’m really not sure. How many kinds of things can a person make?

What are these vessels holding for you right now?

Just air!

And what do you think a change in scale will bring out of the work?

The bigger things are, unfortunately, often the more powerful, especially in relationship to your own body.

Looking back to the very beginning, I wonder if you can tell me about your first experience with art. You trained as a dancer, and your father was an architect. You went to Bennington College and were turned away from becoming a dance major, and studied sculpture instead. Can you walk me back to your first encounter with art-making and when you first saw yourself as an artist?

Bennington was probably the place I discovered that. It was devastating to me that I couldn’t be a dance major. I went there to be a dance major. I had studied dance but I was coming from Los Angeles, and although it is a very sophisticated place, it’s not New York. When I got to Bennington, I realized that the students had been taking dance classes on a daily basis for maybe five years. I’d never done anything like that. I just took the Saturday classes, because I was going to school. I did not realize that people studied like that at that young of an age. I was naïve, and my parents didn’t know—that was a New York thing. So I got to Bennington and realized I was really behind. They said I was much better in art, and I didn’t even think about art.

I was in Isaac Witkin’s sculpture class, and he went crazy for my pieces. And the dance people went crazy with how bad I was. It was such a big deal to get there and get myself straightened out about being 3,000 miles from home, that I just decided to stay. Isaac was a tremendous teacher. I did one sculpture at the beginning of class. I don’t even remember what it was, but everyone in the class was raving about what I had done. To me, I was just doing something.

When did you realize that you could integrate movement and dance into your sculptural work?

I guess I was always really interested in motion and nature. I got involved with wire rope—I have used it up to this moment. That seemed to provide the motion that I was missing from dance. I didn’t actually have to tap my foot or go on a diet to do it.

In the ’70s, when you’re back in LA, you did a project with CETA [Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, a jobs program that employed artists across the U.S.] and so did Senga Nengudi, who you would develop a long friendship and collaboration with. Could you speak to making art in Los Angeles versus making art in New York?

Wanting to finally end up in New York was because I wanted to earn a living. I wanted to be able to sell my work and get cash back for it. That was not going to happen very easily in Los Angeles, it’s just not that kind of place.

You’ve made several public artworks, including a collaboration with the Metropolitan Transit Authority, which is still on view at the 110th St 2/3 stop. Was it important to you to make art that people would encounter in their daily life?

No. I wasn’t bound and determined to be a public artist. I don’t know what I was bound and determined to be. I think I was bound and determined not to starve. A public artist is never known, it’s always an anonymous person. They’re making these things that’ll stand out properly, but maybe don’t have a whole lot of aesthetic value.

How has your idea of what art can and can’t do evolved over the years?

It’s like language, you can do anything, but everybody has to understand that they have a particular interest in limitation. I see my limitations and I work with them. Using steel is a limitation, one which I adhere to for the most part because I don’t have to worry about longevity. If I’m doing a weaving and it’s made out of fabric, that’s a problem because there’s always going to be a huge sensitivity to the atmosphere around it. You have to watch out for mold and insects. With steel, you have none of that. Nobody’s gonna try to eat a piece of steel.

And you can bend wire rope any way you want to. I like linear things, and the wire is linear. I like the way it can mimic nature. And it’s not heavy, so I can deal with it on my own.

Do you feel like you’ve given up anything to stay an artist over five decades?

I never starved to death because I did get an MFA and taught, so I always had a paycheck coming in. What I may have given up is doing more artwork because I was so busy going to bed at night so I could get up and go teach. But everything worked out fine. I enjoyed teaching. My students might not have gone on to be artists, but they did learn something in those classes—I’m sure they did.

Can you tell me about your collaboration with Senga, and where it started?

It started as a series of phone calls. She was home with young children and could not get out of her house. Then the boys grew up and we were still friends and talking about things, so we remained close. I was free to share crazy, wild ideas; it was always a wide open conversation. We laughed a lot too. Laughter is important.

Who else do you feel has left the biggest impact on your career?

Bernard Kester, who was my graduate school teacher [at UCLA], was very encouraging. Susan Inglett, my art dealer, is very encouraging. Who else? I guess enough people for me not to stop and to have the crazy idea I could actually make a living as an artist. Which I have, knock on wood.

If you could give a young artist who looks up to you a few words of advice, what would that be?

Don’t stop. Your family will say, “Don’t do that. Go be a doctor, a lawyer, a teacher. You’ll starve to death.” That is not true: I have not starved to death. In fact, I need to diet.

Does doubt have a place in your creative process?

I have to make decisions all the time. I’ve tossed things that I didn’t think were working and tried to think of ways to make it better. I was fortunate that pretty early on, I was introduced to Susan Inglett. She accepted me and signed me up to have a show. She found she could sell things. All of a sudden, I was a professional. Basically I think one can do what they feel comfortable doing in a really good way. And if you want to do this thing, you can do it because you’re competent at it.

And what’s been the single greatest joy of being an artist for you?

Just making things I wanted to make. Nobody told me to make this thing over here or that thing over there. You are in charge. I knew that I might not ever sell anything, but if I got this MFA, I could probably teach art in the school system, and that’s what I did. They actually paid. I could pay my rent and buy food. I enjoyed teaching. I’ve had a good life. Knock on wood.

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

Tessa Thompson Took Two Years Out of the Spotlight. This Winter, She’s Back With a Vengeance.

On the Ground at Art Basel Qatar: 84 Booths, a Sprinkle of Sales, and One Place to Drink

How to Nail Your Wellness Routine, According to American Ballet Theater Dancers

10 of New York’s Best-Dressed Residents Offer the Ultimate Guide to Shopping Vintage in the City

Sign up for our newsletter here to get these stories direct to your inbox.

in your life?

in your life?