Tip: to map our picks and plan your route, enter the Critic’s Table hashtag #TCT in the search bar of the See Saw app.

Lucas Blalock & Julia Rommel

Bureau | 112 Duane Street

Through February 21, 2026

Nothing, at a glance, suggests that these two New York artists—Julia Rommel, a painter, and Lucas Blalock, a photographer—are a fitting match. But the pairing makes for an intriguing, even brilliant, combination, with the artists’ works creating distinct but complementary melodic lines as they intermix across the two floors of Bureau’s gallery.

Rommel makes post-minimalist, post-geometric abstractionist paintings that remain personal, rejecting any ideal of formal austerity. The Brooklyn-based artist folds her canvases—stretching, unstretching, and restretching them as she paints—which usually results in monochrome passages of rectangles, sometimes triangles, in various configurations, with raised seams (from the folding). If the likes of Ellsworth Kelly or Carmen Herrera deemphasized the presence of the hand with their hard-edged approach, Rommel’s methods produce edges that hint at the alchemy of her process. The margins become central. You can—and should—spend as much time looking at her paintings in profile, as you do straight on; up close, as much as you look from far away. I’ve been a fan of Julia Rommel’s paintings since her solo show “Uncle” at Bureau’s previous location in 2022, and her paintings still feel new in a medium where that alone is a feat.

Rommel’s passages of color had me comparing them to drones or washes of sound in ambient music; her prominent and numerous staples, fixing linen to her wooden supports (with the occasional staple found on the surface of her pictures also), provide a rhythmic element skittering at the edges of her compositions. In this exhibition, Rommel further expands her vocabulary by embracing brushstrokes and polychromal passages of wet-on-wet gesture, as in the stacked horizontal yellow blocks of Musical Guest, 2025, with greens and reds swirling into sunshine tones. In Discipline, 2025, Rommel has stapled a seatbelt-width strip of gray painted linen to create two horizontal bands across the large painting’s surface—an indication that here she’s pushing past folding, moving closer to collage.—John Vincler

The warm analog resonance of Rommel’s paintings contrasts with the lush digital detail in Lucas Blalock’s often disorienting photographs, which similarly demand that you shift your perspective and proximity to their surfaces to try and make sense of them. Take the unpronounceably titled F/D/u/a/n/n/e/c/r/I/a/n/l/g Shoes, 2025, which ostensibly depicts a pair of men’s black leather dress shoes on a metal tray. Blalock’s compelling strangeness derives from a mix of studio and digital effects. The tray is bordered by toothpicks set down on the table end to end, outlining the tray’s rectangular shape at the front and sides and then continuing up the wall behind and to the right. A set of musical notes are digitally superimposed (like emojis on a social-media photo post) above the oxfords. The shoe at left is oddly deconstructed, with its tan leather sole facing out, and looking nonsensically like the skin of an orange peeled away in a spiral. This surreal intervention is a trick of digital editing.

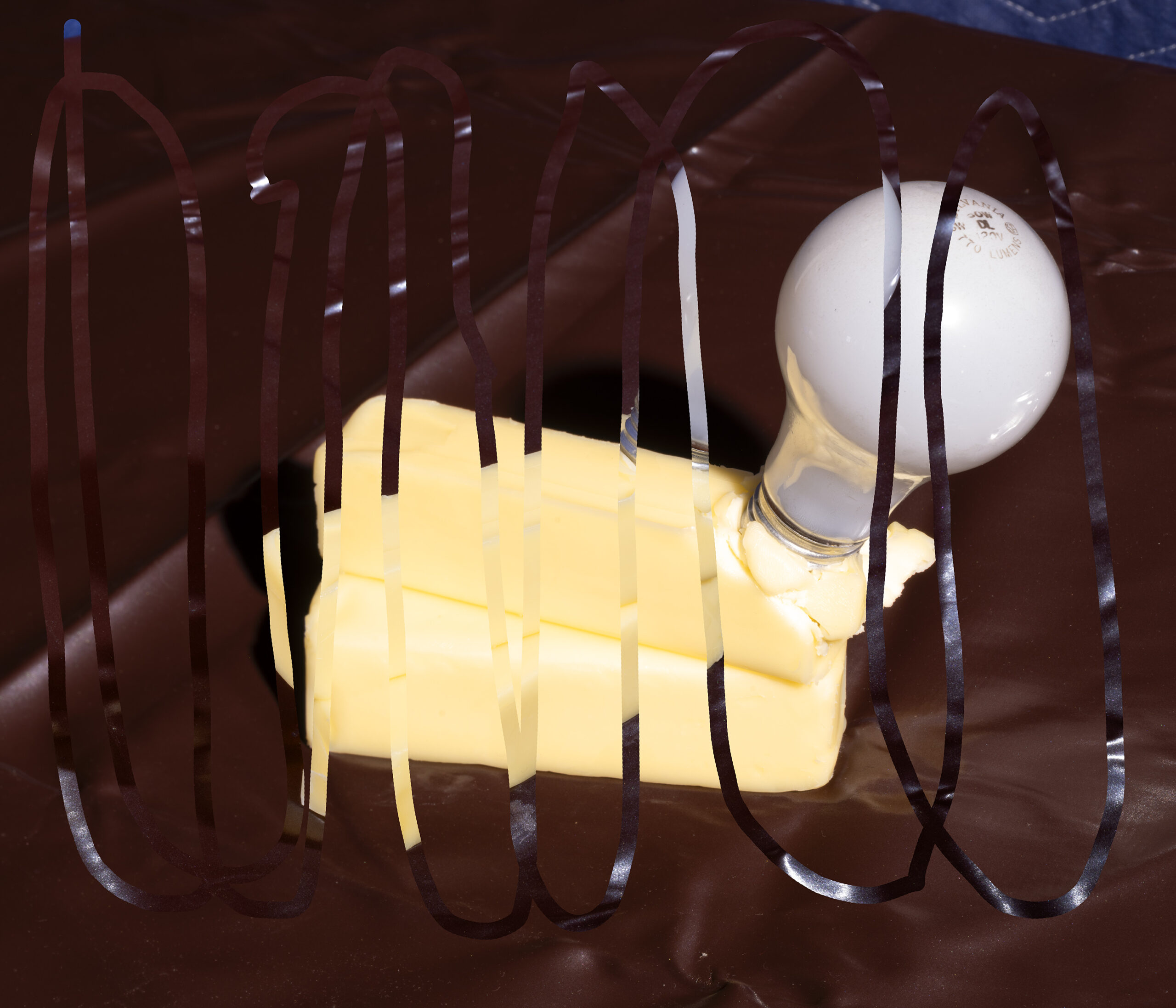

Blalock’s methods are made more transparent in Fat Lamp, 2025, an image of a translucent glowing plastic (maybe?) form, illuminated from within, with a not-illuminated lightbulb emerging from it. The surface of the image is marked by a flowing gesture, moving up-and-down in waves across the image’s surface, seemingly using a Photoshop scrub preset to both reference painting and expose digital trickery that’s usually used to hide imperfections. If Fat Lamp leans into the digital, Hammer, 2025, comically relies entirely on the linguistic and symbolic—it depicts simply a hand-held sickle casting an arc of a shadow on a white background. Its match, the titular hammer, is missing. This is Zohran’s New York after all—it LOLs in this particular context, a stone’s throw from the Financial District.

Both artists play with the processes of doing, undoing, and redoing. Their works are evidence of labor performed for labor’s sake, following a mix of duty, intuition, and a dash of playful absurdity. They finish one, and then they make another. —John Vincler

Tom Burr

Bortolami | 39 Walker Street (upstairs)

Through February 28, 2026

“Journal Works,” the title of the show of Tom Burr’s 15 gnomic, framed assemblages upstairs at Bortolami, aren’t exactly diaristic but they are cooly personal. While trying to parse and contextualize them, I was reminded of that bit of timeless wisdom from John Waters: “If you go home with somebody, and they don’t have books, don’t fuck ’em!”

There are books here: two pages from Heretical Aesthetics: Pasolini on Painting, 2023; the orange cover of a public library copy of Rainer Crone’s catalogue raisonné of Andy Warhol, 1970; Howl and Other Poems, by Allen Ginsberg, 1956; and pages of James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, from the same year. Fragments of books; clothing (Dries Van Noten seems to be a favorite designer); and media, like an Arthur Russell vinyl record; and printed ephemera (a psoriasis drug brochure, an article offering “A critical incident review of the Orlando public safety response to the attack on the Pulse nightclub,” 2017) all find their way into Burr’s compositions. All of them are square, with the array of objects held as shallow reliefs, significantly occluded by geometric shapes in monochrome powder-coated aluminum, inspired by Ellsworth Kelly’s 1957 Sculpture for a Large Wall, first commissioned for the Philadelphia Transportation Building Lobby before making its way to the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

The works date from 2023 to 2025, but their contents stretch decades into the past, gently excavating histories of homophobic violence, AIDS, the closet, as well as quotidian totems of taste and accoutrements of gay life. Rather than diaries, these “journals” (given numeric titles) assemble fragments of a self into often color-matched groupings. They remind me, yet contrast sharply, with Cady Noland’s expansive show at Gagosian late last year: self-excavating and mysterious, they share an industrial slickness, but here the works are intimate and poetic, not jokingly grandiose; they are orderly and not a mess. They reveal rather than cloister off the personal in their sculptural conceptualism. You can browse through these catalogs of the self and find out if you want to spend time with them. I, for one, recommend it. —John Vincler

Arthur Simms

Karma | 22 East 2nd Street

Through February 14, 2026

It is difficult to view Arthur Simms’s show “Caged Bottle” and not start cataloging the amassed objects that make up his intricate composite sculptures. The title work rests atop skateboards above which two forms collide: a sun-faded 101 Dalmatians bicycle bound in hemp and a handmade cylindrical wire folk basket filled with glass bottles and topped first by a bicycle wheel, then by a birdcage. Inside that cage, a single clear wine bottle—the only element not lashed in place—remains theoretically free to rattle.

This arrested motion recurs in Bugs in the Cars, 2024, where an insect preserved in resin crowns a stack of toy cars resting on a roller-skate, all bound together by bubble-gum pink rope. In interviews, the Staten Island-based Simms has traced his impulse toward assemblage back to his childhood in Jamaica, when he’d make toys for himself. Yet elsewhere, playfulness shades to menace: barbed wire coils through Two Buckles, One Foot, 2011, while The Knife and the Hammer, Fear of Aggression, 1994, binds actual blades and hammers into a towering, totemic, cruciform sculpture.

In the center of the gallery stands Sexual Tension, 1992, a hulking form that suggests variously a schooner, a figure, or some spectral architecture. Jute rope coils around a hidden wooden frame, crisscrossing until the cord itself becomes a taut and fibrous skin. What rests within—a painting, maybe—remains tantalizingly obscured. Yet concealment and revelation operate differently across the show. Dreamcatcher IV, 2017, suggests a shopping basket: aluminum wire woven around a wooden skeleton creates a delicate, permeable veil, inside which glass bottles have been placed on bamboo rods and wrapped in rope. The form rests on suspended scooter wheels. Such accumulation demands penetrating, meditative attention: the viewer must painstakingly piece together what each binding constructs and hides. Yet Simms’s compulsive lashing paradoxically creates the conditions for freedom: the wine bottle’s potential tremor, the rope whose weave admits the eye. Constraint and liberation, he suggests, exist not in opposition but in tension, each defining the other. —Will Harrison

Elberto “SLUTO” Muller

Post Times | 29 Henry Street

Through March 1, 2026

Walking down Henry Street with the Manhattan Bridge at your back, you’ll find glyphs and signs all around you. Two standouts are low-hanging mosaics by Elberto “SLUTO” Muller, whose tile works translate his ecstatic, anti-style graffiti into a more permanent form—one of which he installed on Post Times’s exterior wall before he even knew it was a gallery. Two years later, Daisy, 2024, his girl on a motorbike, welcomes you into “Intermodal 53,” a solo show comprised of sculpturally ambitious mosaic works that dissolve the boundary between Post Times and the street outside.

The show’s title refers to the 53-foot shipping containers that dominate freight transport, and it gestures to Muller’s years spent train-hopping. Muller’s work resists domestication. On the windowsill, Muller’s zines, mixtape, and novel sit alongside a wobbling, tile-embossed, pig-snouted, nightstick-carrying cop. Thirty-nine mosaic works fill the gallery—including a glossy-eyed Cheburashka, a full Chinese menu, a canonized Luigi Mangione, and a nitrous-huffer outlined by empty canisters—many dated from the last few months, evidence of his relentless productivity and refusal to repeat himself.

Some of Muller’s most striking pieces incorporate photographs that have been printed directly onto tile, adorned with etched drawings or Pushkin poems, and bordered by solid colors and rubber stamp reliefs that have been tiled into the frame. During the show’s opening, fellow anti-styler Aneko incised her tag upon Muller’s sculpture of Pinhead from Hellraiser, an extension of the street’s collectivist ethos creeping into a white-walled gallery. Muller’s Real Italian Peep Show, 2026, takes close looking even further: peer through a keyhole and you’ll find a miniature-yet-raucous nightclub, replete with a checkerboard dance floor, salacious partygoers, tile inlay, and murals evoking a luxurious palazzo. It’s a microcosm of the show: what appears rough from afar contains its own rigorous-yet-riotous universe. —Will Harrison

in your life?

in your life?