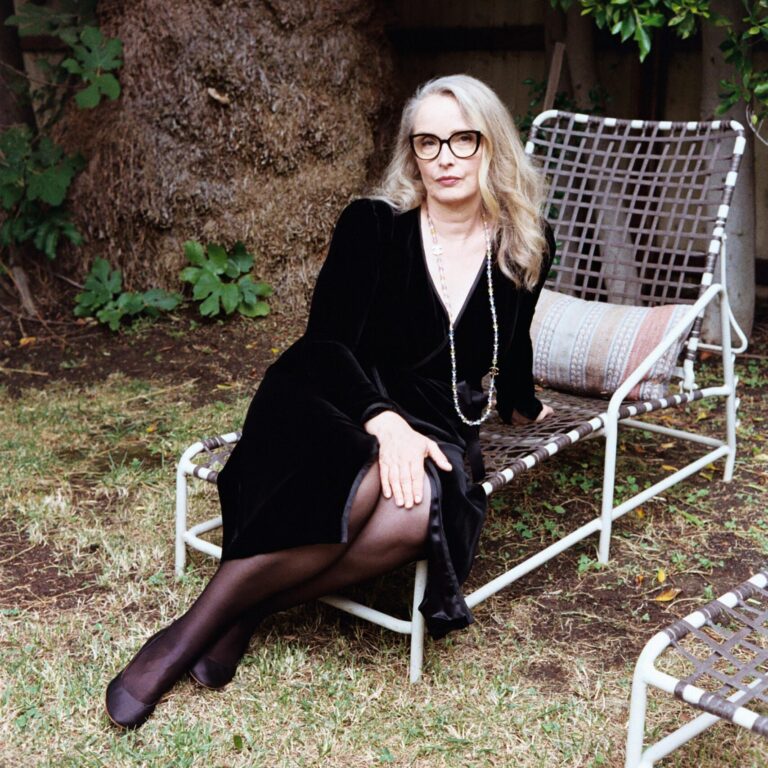

Every industry needs its chaos agent, and thank God the art world has Pat Oleszko. The 78-year-old artist, who has lived in a Tribeca loft stuffed to the brim with her creations since the ’70s, reflects the issues of our time back at us with wit and gravitas through performances that pull from burlesque, commedia dell’arte, and protest movements. Her rich archive of inflatables and costumes is the subject of her first New York solo show in 35 years at SculptureCenter, on view through April.

You have a lot going on these days, Pat. What are you sitting with? What’s on your mind?

It’s so very thrilling to have this [SculptureCenter] show. Then the [Whitney] Biennial… stuff’s out, people see it. But all I really want to do is make work about our descent into fascism and the massive climate problem. I really thought that I was going to be able to make some new work for the SculptureCenter show, but I simply didn’t have enough time. The only way that I can deal with iniquity and the awfulness of the situation is to create work. It’s very frustrating that I’m not able to channel my great sadness and fury into something that’s palpable. I hope once the show is up I’ll have time to start making stuff [again].

You’re not making new work right now, but I can imagine the past few months have had you looking at a lot of your old work—with SculptureCenter, the Whitney Biennial, and your presentation at Art Basel Miami Beach last December. Have you re-encountered any of them in ways that challenge or complicate how you first saw them?

There’s so much work, and in all of that there is the fact that I am the vessel, the armature, the motivation of the stuff… I put myself in so many different situations, and a lot of them were quite brutal.

I’m looking [back] and I’m sort of in awe that I did those things—placing myself in the middle of society where [I] might be welcomed, laughed at, or challenged by any number of people that were viewing it. I don’t have any fear about putting myself out as a fool, but it’s different as a person with experience. I know how to handle the crowd; I know essentially what’s going to happen in a lot of circumstances. But I’m still fearful of what might happen to me in different situations, whether it’s on the stage or in the street. I know much more, but it’s still terrifying. It’s always hard and it’s always easy because that’s what I have to do.

I wanted to ask you about how your experience of vulnerability and labor have evolved over the years. As you said, you’re the instigator for the work. It doesn’t exist without you activating it—whether that’s pressing a button and inflating it or wearing and literally embodying it.

I have journals, and I have kept a record of all my exercise, what time I get up, and how much I weigh for years. The energy has changed, so I’m more watchful of how much energy I can spend in pursuit of this stuff. I still don’t recognize the fact that I’m 78 years old. Inside, I’m just the same. I’m a Taurus, so I’ve had a massive amount of strength to pummel myself to do these things.

The other thing is I’m doing exactly what I want to do. My whole life I’ve been living the exploration of this gift that I discovered. I’m never happier than when I’m working, and the thrill of putting the piece out in public is better than any drug I’ve ever had. If I fail, oh my God.

Failure can be so fruitful, though.

Absolutely. There’s nothing, nothing like failure to propel you. I give my whole self to a project, so if I fail, it’s going to be a magnificent failure. You never make that mistake again. It forces you to grow.

When did you know that this was what you wanted to do—that this was a gift you wanted to claim?

I knew I was going to be an artist in kindergarten because we had to do a self-portrait, and mine was so clearly the best in the class. I always had millions of projects. When I got to college—and going to the University of Michigan at that time, I believe, was like going to the Bauhaus or Black Mountain—there was just a pervasive brilliance with the students and teachers. I had two teachers, Milton Cohen and George Manupelli, and one of them said a few things to the class that made me realize that what I was thinking about could be expressed on my body. I couldn’t learn how to weld—my things kept falling down—so I was working at home and sewing. Then I realized I was six feet tall, so I could hang the work on myself. That was my eureka moment: engaging with the public, with ideas, and putting them out, not in a hallowed white cube.

Who do you think have been the most important conversation or thought partners over the course of your career?

There have been many… Rose La Rose, who was the mentor who ran the strip house in Toledo. Burlesque was a huge influence on my career, and she was the smartest woman I’d ever met. She was an enormous influence—as important as going to art school. I certainly spent a good part of my life in the movies, and Buster Keaton was an example of an undaunting humor and being resolute in the face of adversity, which kind of characterizes what the fool is about. I don’t know how many film festivals I’ve sat through happily in the dark watching him and wishing I could be him.

The use of language has been very important, and a lot of that came from my dad, who spoke many languages and always inserted them in conversation, completely flummoxing us children. I always loved language. The use of language is no different than the use of the body. I can manipulate the body into anything, but still underneath it’s a body that has to walk down the street, take the subway, ride the bike to do the gig… I like writing about the work almost as much as I like making it. And oftentimes an idea will appear in language, like, “Bingo, I have to go do that.” Then I have the greatest time in the world, even though I may not know what the fuck I’m doing with the piece. I’m getting to know it as I’m making it; we all grow together. Then I put it on, and there has to be some language to speak about it. And that language is usually unique to that character.

Have you given up anything to be and to stay an artist?

I haven’t given up on anything. I’m doing exactly what I’m supposed to be doing. It’s the best expression of my talents. Everything that I’ve ever done that has been more pedestrian, I have manipulated into my work. When I was a waitress, every night, it was a different kind of waitress. When I was stripping, I wasn’t stripping like they were…

I mean, I wish I had some more money, but I’m not interested in that. I’m only interested in making a kind of a world that is taking on these different challenges and dealing with that in my own way, so that I can point out absurdity or the tragedy of the moment.

How has your idea of what art can and can’t do evolved?

You try your best, and you do it with as much rigor and thoughtfulness and invention to try to direct attention to something, to speak to people, to motivate them, to make them recognize stuff that they might be hiding from or that might be hidden from them. I don’t have any false expectations about what art can do, but I do believe that art is memorable in a way that reaches many more senses than didactic stuff from governments or organizations, particularly in my field, which is working through humor. You make people laugh, and one, you give them enjoyment. Two, then they have to think about what they were laughing at and why.

I’m not putting myself in the same echelon, but the great humorists have always had a problem being taken seriously. Even though Chaplin and Keaton and Jacques Tati were doing incredible work, it took the world a long time to recognize the fact that it was true brilliance. If you’re good you get a lot of mileage. I have something that will keep me occupied into eternity. I’m happy I went to college and got an education about how to be an artist at all times. Money well spent.

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

13 Books Our Editors Can’t Wait to Read This Season

With Art Basel Qatar, Wael Shawky Is Betting on Artists Over Sales Logic

Jay Duplass Breaks Down the New Rules For Making Indie Movies in 2026

How Growing Up Inside Her Father’s Living Sculpture Trained This Collector’s Eye

It’s Officially Freezing Outside. Samah Dada Has a Few Recipes Guaranteed to Soothe the Cold.

Sign up for our newsletter here to get these stories direct to your inbox.

in your life?

in your life?