After seven years, Gus Van Sant has returned to feature filmmaking. The prompt that got him back behind the camera: We’re going to your hometown in Kentucky to shoot a hold up. We leave next week.

Dead Man’s Wire sees Bill Skarsgård and Dacre Montgomery reenact a 1977 case in which Tony Kiritsis took mortgage broker Richard O. Hall hostage on account of his alleged exploitation of the working man—chiefly, Kiritsis himself. The project, released in theaters earlier this month, falls into Van Sant’s long lineage of broke boys, local crime, and working class antiheroes. His source material for these stories ranges from Shakespeare plays to the Columbine school shooting.

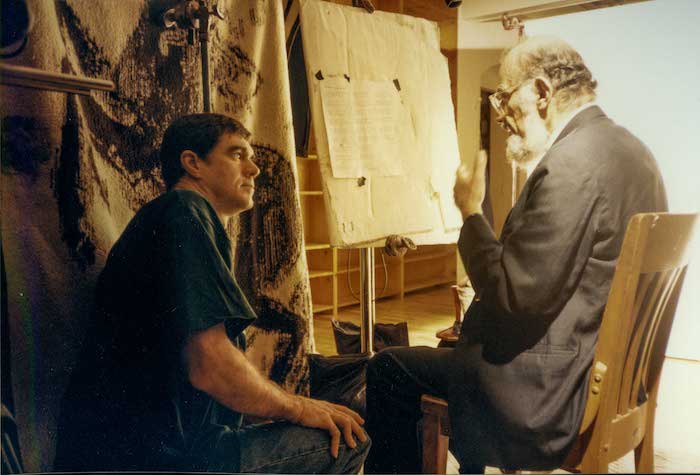

He’s a creative known for both frequenting and fostering a downtown scene that, in the ’80s, included regular dinners with William S. Burroughs; in the ’90s, music videos with Allen Ginsberg; and over the years, collaborations with three Phoenixes, two Skarsgårds, and too many street castings to count.

When he calls from Los Angeles, characteristically donning a plaid button down and reclining with the confidence of an interviewee who knows he’s been making these calls longer than I’ve been alive, the director takes me through these myriad inspirations and crossed paths, and recommends a few texts that set his own winding career on its course.

You were sent the script for Dead Man’s Wire. Was that the first that you learned about Tony’s story?

I didn’t know about the story. The biggest thing about [the project] was that Cassian Elwes, the producer, needed a director right away and actors because he had secured an incentive from Louisville, Kentucky. I was born in Louisville and my family is from Kentucky, and we had to do it right away. That was interesting, that we needed to literally leave the next week. Then I read the script and it was an amazing script.

So you just grab Bill, head to set. How did he come into the project if it was all moving pretty fast?

He was a person that I thought of because I had seen a number of his films and thought that he would be really good for this role. And I thought, as a counterpoint, that Dacre Montgomery would be good. Cassian, his reaction was that it was gonna be harder if we use those guys—they were well known, but they weren’t super well known. But he also saw the value in their talents, so he allowed me to have them.

It’s a funny thing to say about Bill Skarsgård. Particularly young people, love him for all of these just strange, oddball characters that he’s played.

Exactly what I thought. And I had directed his dad [Stellan Skarsgård] in Good Will Hunting, so I felt I knew the family a little bit.

On set, were you like, “Your dad used to do this just the same way”?

He wanted to know whether his dad invited me over for dinner, which he didn’t. I’m not sure why. He was surprised that he didn’t. He’s like, “You’re kidding, cause Dad cooks for everybody all the time.” But we didn’t talk necessarily about process. I did, when I first was talking to him, say that Stellan would really go for almost any idea. If you had an idea of something that he could do in a scene, he would always try it. He would never shy away. All the other actors on that movie, or in general on all the movies, there’s usually a hesitation. Would that work? Would that make me look bad? It wasn’t in his mind.

Either now or when you were younger, do you find yourself gravitating towards books about filmmaking, referencing what other directors or other filmmakers have done? Or do you like to pull from outside sources, read about other kinds of creatives?

When I started out, or before I was even making long-form films, I was reading Hitchcock/Truffaut, in which Hitchcock and Truffaut talk about every film that Hitchcock had made, so there’s like 40 films in it. There’s a great book about the making of a John Huston film called Picture. I would pretty much read whatever I could find when I was in my 20s and 30s, and eventually, I started to rely more on what I was seeing rather than things that have been made in the past. The style of filmmaking had been upended by MTV. Oliver Stone grabbed onto the MTV video style, mixing 8mm with 35 and handheld with tripod stuff and just throwing everything into a blender. From there, just stuff that’s happening online, all the different TV shows or something like TikTok. The filmmakers don’t know any rules, so they’re just creating new forms. Those are the types of things that I find interesting now because it’s working its way into the quote unquote film culture, and it’s things that seem worthy of use.

I wanted to ask you about your work with William S. Burroughs and what that collaboration meant to you. Could you see yourself getting into work like that with a contemporary author?

Well, he played a character in Drugstore Cowboy, and I did a video called Thanksgiving Prayer. I did one with Ginsberg called Ballad of the Skeletons, and aside from those things, I just knew them socially. Burroughs lived in Kansas and I drove across the country a lot, so I would stop in Kansas. It was a good place to stop and then usually have dinner or hang out a little bit. I found out much later, almost the last time I saw him, that I reminded him of a friend of his in the ’30s. I realized I had this whole other existence for him that I didn’t know about. I know what he means, like sometimes you meet somebody that reminds you very much of somebody else that you knew really well. My original thing was doing a short film, The Discipline of D.E., which was from a short story that he had done. Other than that, I always toyed with the idea of doing something for Naked Lunch and maybe someday I could.

Did you see the Queer adaptation from Luca Guadagnino?

That was interesting. I don’t think it’s in the film, but [Burroughs] did say something about that particular book, which was basically about the accidental shooting of his wife when they were playing this William Tell. She would put something on her head and he would shoot it off of her head, and he missed. He had claimed that the day before that happened, they were living in Mexico and he was in the town that they were living in, and with no warning, he just burst into tears for no reason. So he said, “If that ever happens to you, watch out,” because the next thing that happened was he shot his wife. He had this whole thing about being forewarned in a way.

I feel like that would freak me out for the rest of my life if I ever spontaneously burst into tears. How does your reading practice fit into your life now? Do you gravitate towards fiction, nonfiction?

I’m usually reading biographies. Right now I’m reading one about Edward Gorey. Looking at my bookcase right now, there’s one of Derek Jarman. I can see Walter Benjamin’s Illuminations. There’s a John Waters book called Director’s Cut. Tennessee Williams, I’m reading a lot of his short stories and plays. Should I get my books out?

Yes, please! Do you have a book list on your laptop?

They’re just the actual books, my iBooks. One that I liked a lot was Stan and Gus about Stanford White and the sculptor that he worked with named Gus. They made a lot of things, turn of the century things, together. William Goldman, Adventures in the Screen Trade, is a good movie book.

One question we like to ask is if there’s one book someone should read if they want to get to know you.

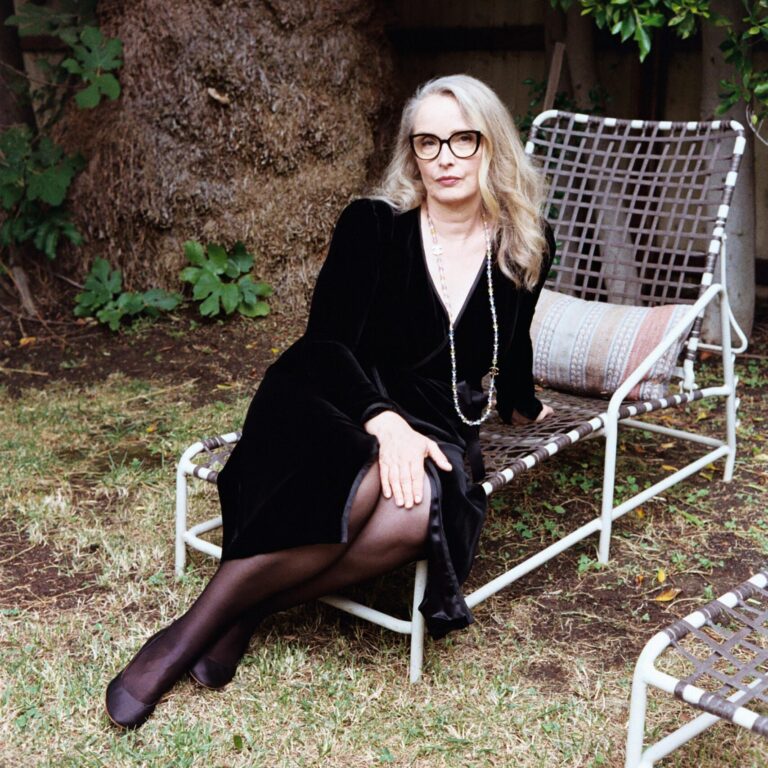

Well, there’s a book by Katya Tylevich. She wrote a book about me. So you probably need that.

You know, a lot of people can’t say that.

Gus Van Sant’s Required Reading

Sometimes a Great Notion by Ken Kesey, 1964

(Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

“That’s a very sprawling novel about a Northwest logging family. A kind of old-fashioned Thomas Wolfe kind of book. It’s about America, it’s about family, family difficulties, unions. It’s a great book that I have around that I sometimes just like to read sections of it.”

Naked Lunch by William Burroughs, 1959

(Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

“It’s a good one. Also one of those types of books.”

Ulysses by James Joyce, 1922

(Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

“I might go back to that.”

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

13 Books Our Editors Can’t Wait to Read This Season

With Art Basel Qatar, Wael Shawky Is Betting on Artists Over Sales Logic

Jay Duplass Breaks Down the New Rules For Making Indie Movies in 2026

How Growing Up Inside Her Father’s Living Sculpture Trained This Collector’s Eye

It’s Officially Freezing Outside. Samah Dada Has a Few Recipes Guaranteed to Soothe the Cold.

in your life?

in your life?