This week, we welcome another artist-critic to the Critics’ Table, painter Sam McKinniss, who sings the praises of an undersung Finnish painter of the 20th century. He writes about Helene Schjerfbeck‘s first major institutional survey in the U.S., at the Met. Also on Museum Mile is Joan Semmel‘s career-spanning show at the Jewish Museum, which proves that her recent icon status is well-deserved, our critic Johanna Fateman argues—as well as some 50 years overdue. And artist Ajay Kurian, who has written for TCT before, looks at the work of Marguerite Humeau, creator of mythic ecosystems, on view at White Cube, just a few blocks away. Tip: to map our picks and plan your route, enter the Critic’s Table hashtag #TCT in the search bar of the See Saw app.

Helene Schjerfbeck

Metropolitan Museum of Art | 1000 Fifth Avenue

Through April 5, 2026

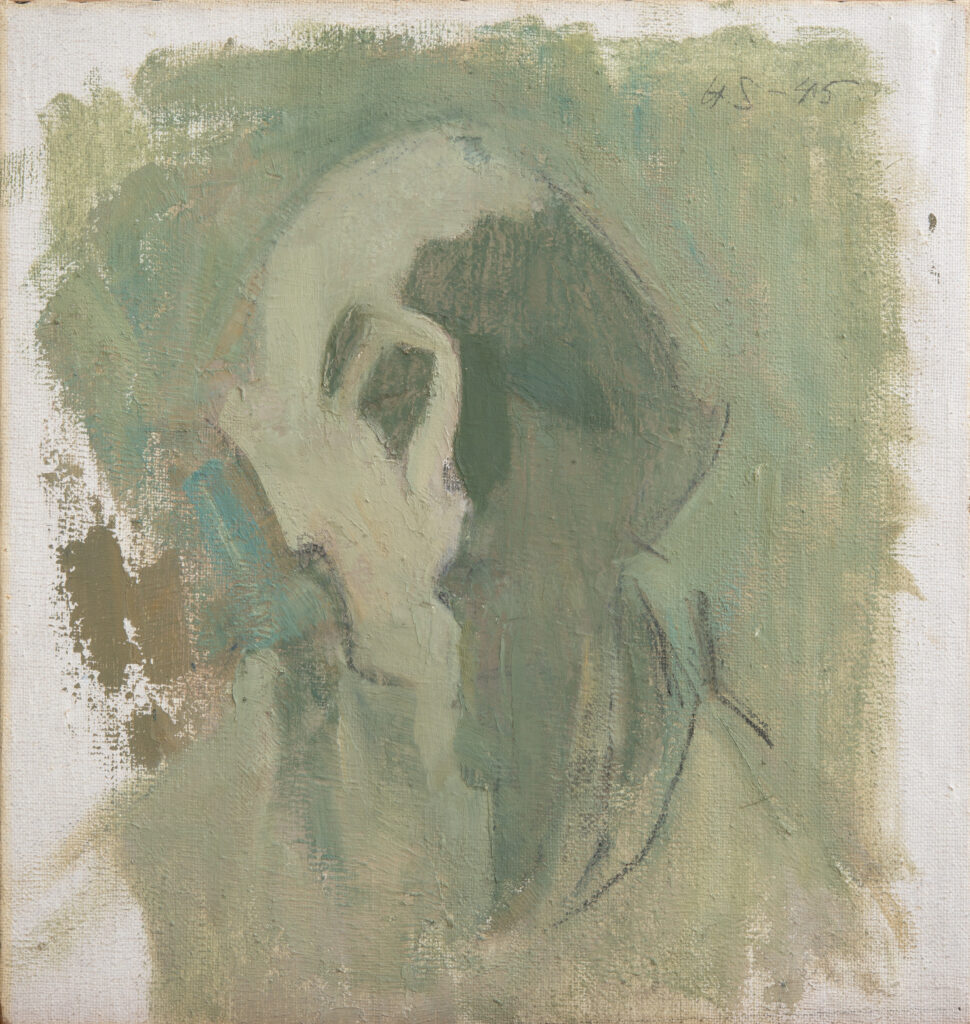

Helene Schjerfbeck is born in 1862 in Russian-controlled Helsinki, a sickly child in occupied territory. Her genius is evident from the start. She is recognized as a prodigy at around age 11. The Finns pay for her study and travel to Paris. She goes also to Florence, St. Ives, and elsewhere in Europe. She returns to Helsinki a sensation, basically. But in midlife she is duty-bound to care for her aging mother in lonely Hyvinkää, north of the capital. There, in relative isolation, she invents her singular, confounding style. Then World War I, the Finnish Civil War, independence from Russia, World War II. She evacuates Finland to a hotel in Sweden. She dies there, next to her easel, in 1946. Almost no one in this country knows anything about her work. Go know.

Schjerfbeck is Finland’s best modern painter. She is more fascinating, more troubling, and certainly more elusive than Norway’s best modernist, Edvard Munch, with whom she is sometimes compared. Same goes for the Dane, Vilhelm Hammershøi, whose oeuvre has attracted considerable appreciation on our shores for at least the last decade. Schjerfbeck is likewise more interesting than James McNeill Whistler, her American contemporary, with whom she is also sometimes compared. It shouldn’t be a contest, and yet these are the stakes of “Seeing Silence: The Paintings of Helene Schjerfbeck” at the Met.

This quiet revelation, curated by Dita Amory, unfolds in four chronological sections. It begins in early life and career. It concludes with the harrowing work of an enfeebled old woman: self-portraits made from a bedside mirror. Self-confident as well as self-effacing, graphic and yet subtle, pensive as well as aggressive… The mature paintings strike out at something, but what? Good grief. Or, grief made good through acts of beauty. What we recognize is the elegant mystery of a private life softly embroiled in total, global upheaval. —Sam McKinniss

Joan Semmel

Jewish Museum | 1109 Fifth Avenue

Through May 31, 2026

To the left, upon entering the gallery, three paintings from the 1970s show Joan Semmel holding the sexual revolution to its word. As the women’s movement sought to level the playing field, she rotated the picture plane to deal with the horizontal space of sex and self-observation, presenting the POV of the reclining nude. The canvas that takes pride of place on the first wall in Semmel’s abbreviated survey “In the Flesh” at the Jewish Museum, demonstrates her breakthrough gesture—the reversal or collapse of the patriarchal art-historical artist-model divide—very directly. Through the Object’s Eye, 1975, as it’s titled, is a radically foreshortened view of Semmel’s own body, cropped, from the collar bone down. The composition can be seen as a lush and nervy turning-of-the-tables, with something like Courbet’s Origin of the World, 1866, in mind. Not quite as nervy, perhaps, as the pair of electrifying “fuck paintings” (the artist’s other term for her “Erotic Series”) that completes the trio: each of these floats an entangled couple, viewed as though standing at the foot of the bed, in an etheric field of color. I love the yellow one especially.

Ten of the 16 paintings on view are from this blazing early period, but the others show Semmel’s fiery rigor vis à vis the nude (her own unclothed body in various positions) undimmed throughout the subsequent decades. Her approach expands, and the emphasis of her critique—her dazzling challenge to what a woman should do, be, look at, look like—shifts over time as her body changes. The four-panel, panoramic Skin in the Game, 2019, features a layered, time lapse-effect procession of figures at the center; on either end, Semmel reprises the evergreen trick of Object’s Eye, with its receding diagonal composition, but with a much older body as her model. (The artist is now 93.)

As a bonus, we get a vest-pocket show-within-a-show that Semmel has curated from the museum’s collection—a salon-style installation of mostly small works from artists as varied as Man Ray, Alice Neel, Gordon Parks, Judith Bernstein, and Nan Goldin. It highlights Semmel’s engagement with history, from European modernism to the American women’s art movement, and functions to locate her on a kind of map, in the mix. For predictable reasons, critics and curators slept on this astonishing body of work until rather late in the game. How embarrassing for them: Joan Semmel is obviously one of the great figurative painters of our time. —Johanna Fateman

Marguerite Humeau

White Cube | 1002 Madison Avenue

Through February 21, 2026

Marguerite Humeau has long looked to other species—termites, bees, “weeds”—not as metaphors, but as collaborators in thinking outside an anthropocentric logic. At White Cube, her new show “scintille,” inspired by her travels through cave systems in West Papua, names the cave and its most mythical inhabitants—bats—as collaborators, establishing a world where perception, action, and meaning emerge collectively.

Just inside the ground-floor gallery, a sculpture (whose title is of a typically long length for these works) stands apart from two towering guardian forms. Centurience: possessing the primordial patience to outlast catastrophe by barely moving at all, knowing that sometimes the greatest revolution is simply refusing to hurry toward extinction. In darkness, there is no shame in remaining still, unfinished, and forever young. Completion is a kind of death, while eternal youth swims on for a hundred years, 2025, as it’s called, is smaller in scale and shows a tiny, frosty pink creature perched on a seemingly younger stalagmite. The piece reads as a guide to the exhibition. The delicate, blown and cast-glass being—part anemone, part axolotl—unfurls two billowing forms from its head. These feel less like organs than auguries: sensory structures without analogy, suggesting ways of knowing that cannot be mapped cleanly onto human systems. The larger stalagmite-like sculptures, standing like geo-biological sentinels, lift the eye upward to their proposed sources of origin—mirrored glass spheres ascending in size, like droplets. Matter appears to grow, pulse, and remember.

In the gallery upstairs, color-shifting glass bat-forms hang throughout the space, mercurial and alert. Inspired by the radically different social and perceptual worlds of these animals, they feel alive precisely because they resist fixity. They are symbols in motion. Where the exhibition strains is in its language. Humeau’s neologisms and portmanteau titles—inspired by the logic of John Koenig’s Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, 2021—pin these uncertain states too neatly in place. In the artist’s shadowy world, which invokes echolocation, darkness, and untranslatable sensations, her objects become less emotionally powerful when the surrounding language is itself treated like a butterfly specimen: newly named, carefully labeled, and immobilized.

Over the two floors, 12 works on paper in arched frames want to operate as portals. But the frames read too much like signposts towards ritual in contrast to the sculptures’ capacity to initiate new ceremonies. And while “scintille” imagines a world of symbiosis, it is not one without violence. Transformation always carries some: Individuation and the carving of categories do damage. Yet the deeper tension here lies not within the exhibition’s internal logic, but between the stories we have inherited and those this exhibition proposes: stories built through patience and accretion, where change unfolds collectively and on timescales closer to geology than biography. —Ajay Kurian

More of our favorite stories from the Critics’ Table

It’s Only January, But Yuji Agematsu Is Already My Artist of the Year

Escape Into Cute: Kittens and Puppies Are Invading Downtown New York’s Art Galleries

Sign up for our newsletter here to get these stories and the Critics’ Table direct to your inbox.

in your life?

in your life?