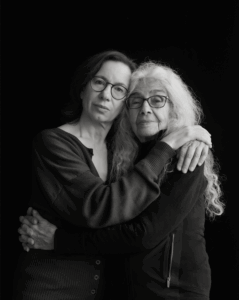

What does it feel like to grow up inside an ever-changing sculpture? For Mariah Nielson, that living work of art was the Blunk House, built by her father JB Blunk in the 1950s from entirely salvaged materials in Northern California’s Point Reyes Station. Every wall, chair, and corner of the home was envisioned as a facet of “one big sculpture,” where art, craft, and daily life were inseparable.

Today, as the director of the JB Blunk Estate, Nielson continues that vision through Blunk Space, the estate’s gallery, pairing her father’s work with that of contemporary creatives. The current exhibition, “100 Candleholders,” showcases a network of makers connected by taste or legacy to the sprawling property and home.

These days, Nielson’s approach to collecting is still inseparable from her upbringing—and she’d like to keep it that way. Her father’s is a philosophy that guides both the objects she surrounds herself with and the exhibitions she curates. Here, she tells CULTURED exactly what those lessons are, and how she aims to keep them in practice.

Where does the story of your collection begin?

The story begins at the Blunk House, the home my father, JB Blunk, built by hand in the 1950s using entirely salvaged materials. The house is his masterpiece—a living sculpture—where nearly everything was made by my family or by artist friends, blurring the line between art, craft, and daily life.

Growing up in the Blunk House means living inside a total work of art. When did you first understand that what surrounded you was rather unique?

I began to fully appreciate the Blunk House as a total work of art in my early 20s, when I was studying architecture. It was then that I understood how rare it was to grow up in a home my father had built entirely by hand, and how deeply sculptural the space itself is. Around that time, I also met historian and curator Glenn Adamson, who had interviewed my father for the Smithsonian Archives. Glenn’s interest in my father’s work helped place the house within a broader historical context and deepened my understanding of its significance.

Your father described the house, garden, and studio as “one big sculpture.” How has that idea shaped the way you think about collecting and living with art?

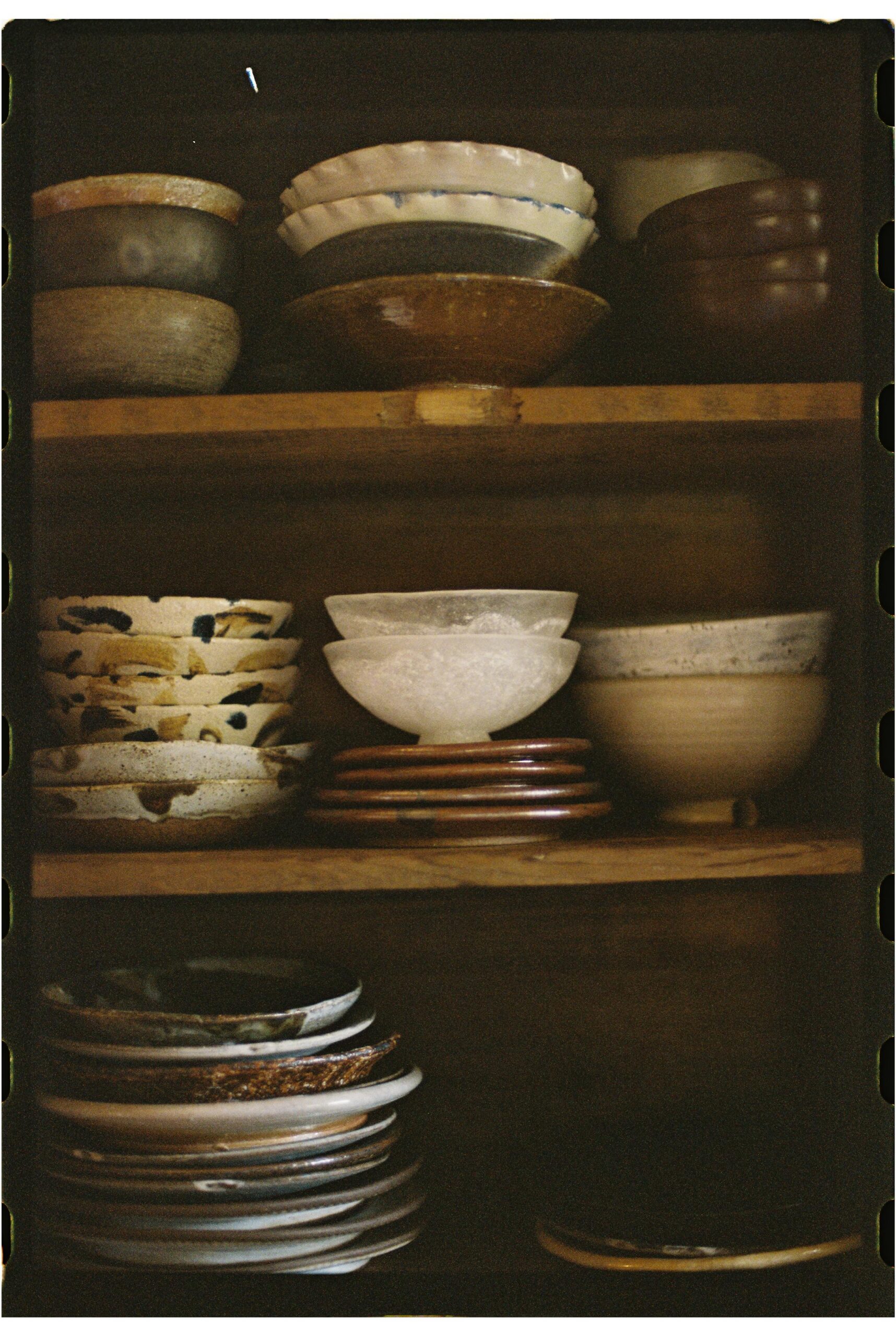

In a very practical, embodied way. It’s encouraged me to see things around me as functional art rather than precious objects. My father always said, “Nothing is precious”—he wanted people to truly live with his work: to sit on it, eat from it, look at it every day, move it around, and engage with it fully.

Everything in our home also had a story or a personal provenance, and that has stayed with me. The objects I live with now are tied to relationships and experiences—pieces from friends or family, things collected while traveling, or gifts from artists and companies I have personal connections with, like Nodi or Birkenstock. That sensibility even extends to my wardrobe.

How do you discover new artists or work? How is that borne out in the exhibitions you mount?

I discover new artists primarily through my network of artist and collector friends, as well as through travel. These relationships and encounters naturally shape the exhibitions I mount. Our current exhibition (“100 Candleholders“) is a perfect example of this extended network in action. All 100 artists in the show are connected to the JB Blunk Estate in some way—through personal relationships, through their galleries, or through artists whose work I’ve encountered while out in the world.

Every collector has made a rookie mistake or two. What was your most memorable?

Not holding on to a Morris Graves painting that was gifted to my father by Morris in the early 1980s.

Which artists are you currently most excited about and why?

I’m currently most excited about Ian Collings, Cross Lypka, and Marina Contro. Ian’s approach to stone carving is sublime, Cross Lypka are truly pushing the boundaries of clay as a medium, and Marina is elevating weaving to the level of fine art.

Your collection spans design, craft, and artwork. What threads connect the objects you’re drawn to?

The threads all loop back to the Blunk House and my father. Many of the artists whose work I collect come into my life through the JB Blunk Estate, and those connections often grow into friendships and, eventually, acquisitions. It’s a joy to support artists whose work I truly believe in.

Which work in your home provokes the most conversation from visitors?

My father’s penis stools… they never fail to spark conversation. He created a series of stools inspired by the phallic form, and they are eye-catching, to say the least.

When you encounter an artwork or object, what are the qualities that never fail to draw you in?

I’m drawn first to the material itself and how it has been worked or manipulated by the artist. Sometimes it’s the way two or three materials are combined. What captures me most is what is now often called the “material intelligence” of the maker—the thoughtfulness and skill with which the material is handled.

Design discourse and collecting, in particular, is very susceptible to trends. What do you think is in vogue right now? What do you attribute that trend to?

There’s a growing interest in collecting work that will truly last—pieces that feel destined to stay in a collection over time. People are investing in art and design that is personal and specific to their homes and larger collections, rather than chasing fleeting trends. The focus feels more intentional: acquiring work that is meaningful, enduring, and able to deepen in value—emotionally as well as aesthetically—the longer you live with it.

As director of the JB Blunk Estate, you work closely with questions of preservation. How do you balance conservation with the belief that objects—and spaces—are meant to be used?

I believe that good design gets better with use. Objects and spaces develop both a literal and energetic patina over time, which only adds to their beauty. Conservation is important, but I balance it with the understanding that these works are meant to be engaged with, lived with, and experienced.

How does the Northern California landscape influence your relationship to art and design?

Growing up in Northern California, I developed a deep appreciation for natural materials and organic forms. The landscape—the shapes, colors, and scale of it all—has profoundly shaped the way I engage with art and design.

If you could snap your fingers and instantly own the art collection of anyone else, who would it be and why?

I would choose Gemma Holt and Max Lamb, because they’ve created so much of the art and design they live with and have such impeccable, discerning taste.

The Blunk Space art and design gallery hosts exhibitions which combine your father’s legacy with contemporary talents. Do you ever find yourself collecting from these shows?

I’ve purchased work from nearly all of our exhibitions, because I genuinely believe in—and want—the pieces we present!

in your life?

in your life?