“I once heard someone, upon entering Beth Rudin DeWoody’s home and spotting a Tom of Finland and many other queer-themed works, say, ‘It looks like a gay man lives here,’” recalls Laura Dvorkin, the co-curator of the Bunker Artspace. It’s not the expected take on the storied patron and Artspace founder’s collection. But DeWoody is cementing her perennial dedication to the queer canon with “Beyond the Rainbow,” a new show of LGBTQ+ work organized by Dvorkin and the Palm Beach space’s co-curator Maynard Monrow, as well as 19 other artists, curators, gallerists, architects, and writers.

Inspiration first struck when DeWoody visited Paris’s Centre Pompidou two years ago, and took in “Over the Rainbow,” a similar celebration of LGBTQ+ creatives. “That experience sparked the idea to create an exhibition of our own at the Bunker Artspace—one that honors the LGBTQ+ community and their art, impact, and activism at this pivotal moment, and in this crucial place: Florida,” explains Monrow, nodding to the fact that since his election in 2019, the state’s governor, Ron DeSantis, has been pursuing an aggressive campaign to roll back protections for queer families, limit healthcare for trans citizens, and prevent education on gender and sexuality in schools. (The Bunker Artspace also stands a mere 15 minutes from Mar-a-Lago.)

DeWoody’s desire to weigh in on the state’s political climate is a natural extension of her longstanding engagement, says Dvorkin, who points to the patron’s support of organizations like God’s Love We Deliver dating back to the height of the AIDS crisis. The new show, open by appointment Dec. 7 through May 1, 2026, features work by boldface names like Catherine Opie, Andy Warhol, Nicole Eisenman, and Lyle Ashton Harris.

Dvorkin and Monrow note less of a focus on including only queer artists, and more of an interest in identifying pieces that limn queer themes of identity, diversity, and representation, or that resonate personally with the panel of curators. “The installation process was an exciting and deeply meaningful journey—one that revealed unexpected connections and conversations,” shares Monrow. “For instance, we placed a Martin Wong drawing of skeletons alongside a handmade exhibition announcement by Felix Gonzalez-Torres and a General Idea work on paper titled AIDS (Reinhardt). Together, these pieces form a powerful curatorial statement on the AIDS epidemic.”

Elsewhere, a room resembling an “old-school library” is filled with books and other work by the likes of Joe Brainard, John Ashbery, and Allen Ginsberg. There are also spaces dedicated to the late Nancy Brooks Brody and Pippa Garner, who was approached to be a curator, but died before the exhibition was put together. Though the Bunker is now flush with these kinds of critical tributes and pieces, Dvorkin wants to ensure her community knows that “first and foremost, this exhibition is a celebration.” Here, a few of the litany of curators share a look inside the making of the sprawling show.

Alina Perez

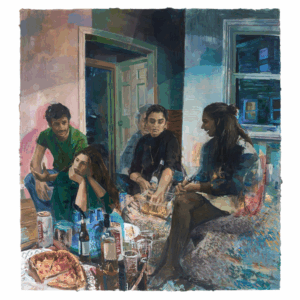

Artist Alina Perez’s monumental works on paper interrogate her own memories, reworking and reentering them across pieces shown everywhere from James Cohan Gallery to El Museo del Barrio.

What’s one thing you hoped to capture in your selection of 10 works?

That queerness is an open category, defined by its ability to transcend a singular definition, aesthetic, location, or narrative. That being alive is both an absurdity and a miracle, and that having appendages can sometimes feel like having horned claws. A fluctuation between feeling trapped, and then weightless. That an environment that feels “ill-fitting” can at the same time be in perfect harmony with us. That perhaps we still belong to one another, even while we pursue and fight for our respective autonomies.

Is there a piece from the canon of LGBTQ+ artists that helped shape your work? How do you see it in conversation with your selections here?

The first thing that pops into my head is The Two Fridas by Frida Kahlo. Her ability to witness the multiple parts that make up who she is struck me as a younger artist yearning to make sense of my own pain. The exposed hearts, her still expression, and the way she holds her own hand created a gut-wrenching experience in me that brought me to tears the first time I saw the painting in person. It is within this amalgamation of embodied emotions (and quite simply the mere act of her creating this piece) where I find an intrinsic queerness that speaks to our shared histories, personal endurances, and the insatiable desire to be seen. I was also recently moved to tears when I saw Harold Stevenson’s painting The New Adam. The fact that this work was originally pulled from its intended inclusion at the Guggenheim in 1963 further speaks to the ways in which queer art and queer artists have always hit a soft spot of what is or isn’t allowed to be publicly displayed, celebrated, explored, or even spoken about.

Ryan McNamara

Ryan McNamara works across a torrent of mediums—including performance, installation, photography, drawing, and sculpture—and has shown at institutions ranging from MoMA PS1 to the Guggenheim.

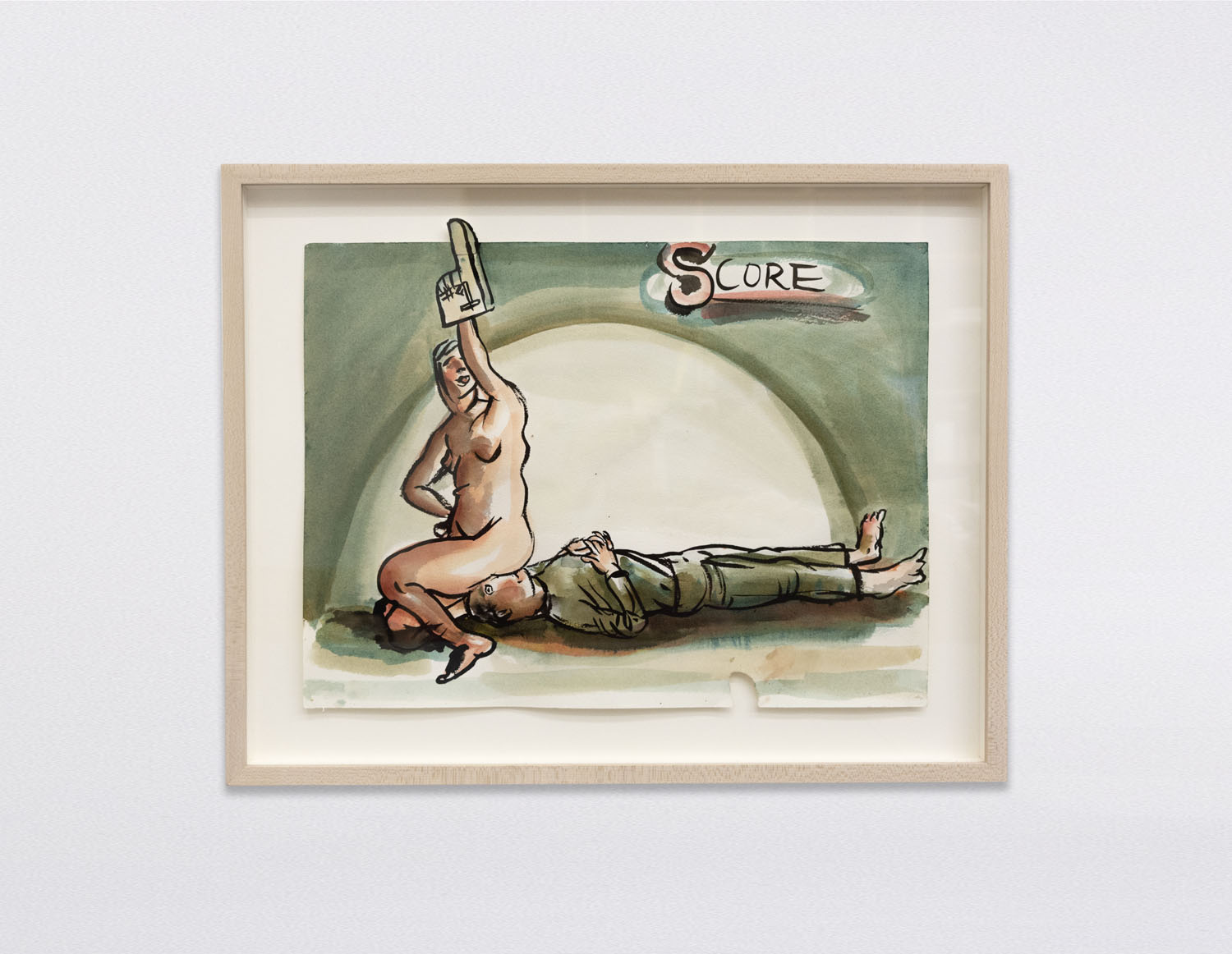

What’s one thing you hoped to capture in your selection of 10 works?

I wasn’t chasing a theme so much as admitting that the theme already existed: we all know each other.

What kind of research or exploration did you do to put together your selection?

I scrolled through my contacts and my memories; then I searched Beth’s collection. It turned out to be the same group of people in both.

What role do you think art plays in shaping the queer community, and its larger place in American culture?

Without queer art, I’d have no openings or performances to bump into queer people at and remember why I like them. It’s our social infrastructure disguised as culture.

Is there a piece from the canon of LGBTQ+ artists that helped shape your work? How do you see it in conversation with your selections here?

Nicole Eisenman’s sentence “Queer art is art made by queer people” is the canon as far as I’m concerned.

Steven Henry

Following positions at the New Museum and the Dallas Museum of Art, Steven Henry now works as a senior partner for New York’s Paula Cooper Gallery, where he has overseen a litany of bold programming and the opening of the gallery’s first location outside of New York, in Palm Beach.

What’s one thing you hoped to capture in your selection of 10 works?

My selection focuses on self-portraiture, conventional and non-conventional. One of the burning questions in these times is how self is defined and who gets to decide that.

What role do you think art plays in shaping the queer community, and its larger place in American culture?

At a time when the narratives of multiple groups of people are being erased and fear-mongering has become a political means to an end, art can and does provide an essential space for expression.

Is there a piece from the canon of LGBTQ+ artists that helped shape your work? How do you see it in conversation with your selections here?

Happily, Beth’s collection includes Robert Gober’s profound self-portrait in a wedding gown—an iconic and unabashedly political work that helped focus my choices.

Kalup Linzy

Artist Kalup Linzy’s work, which ranges from multimedia compositions to elaborately constructed drag personas, is held in collections at institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

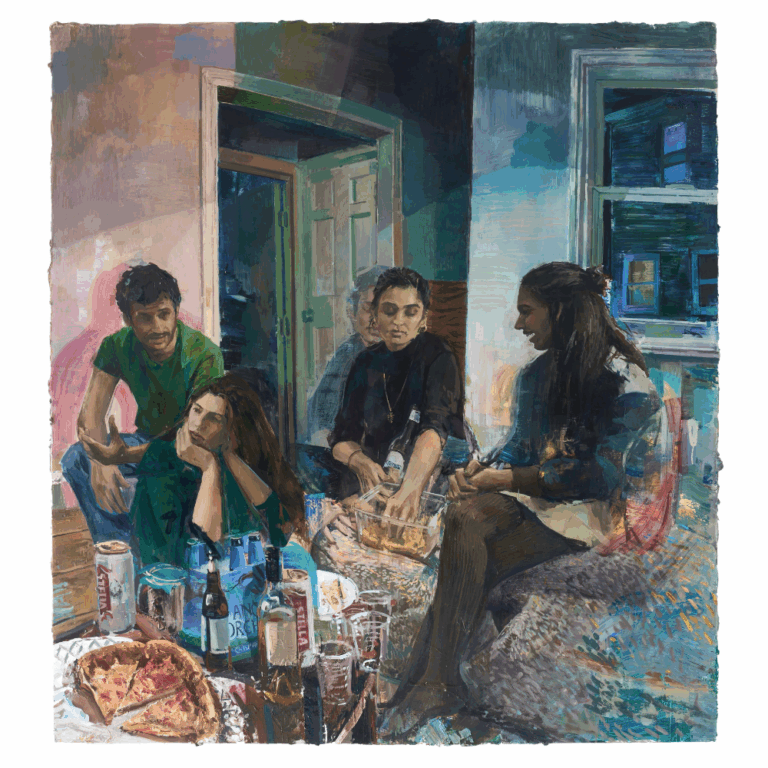

What’s one thing you hoped to capture in your selection of 10 works

I chose works that fully embraced queer identity. I have had a push and pull with my queer identity and was drawn to the works that served no fear, no shame.

What role do you think art plays in shaping the queer community, and its larger place in American culture?

Art inspires, influences, and shapes ideas, perspectives, emotions, and most importantly, imagination. Queer artists and art have always and will always be a part of the discourse that helps shape America.

Is there a piece from the canon of LGBTQ+ artists that helped shape your work? How do you see it in conversation with your selections here?

Lyle Ashton Harris’s Construct #10 (Referenced as Degas), 1989. I discovered this work in the catalogue for the 1994 Whitney Museum exhibition “Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art.” It spoke to me because of its boldness and the same is true for my selections in this exhibition.

Sarah Thornton

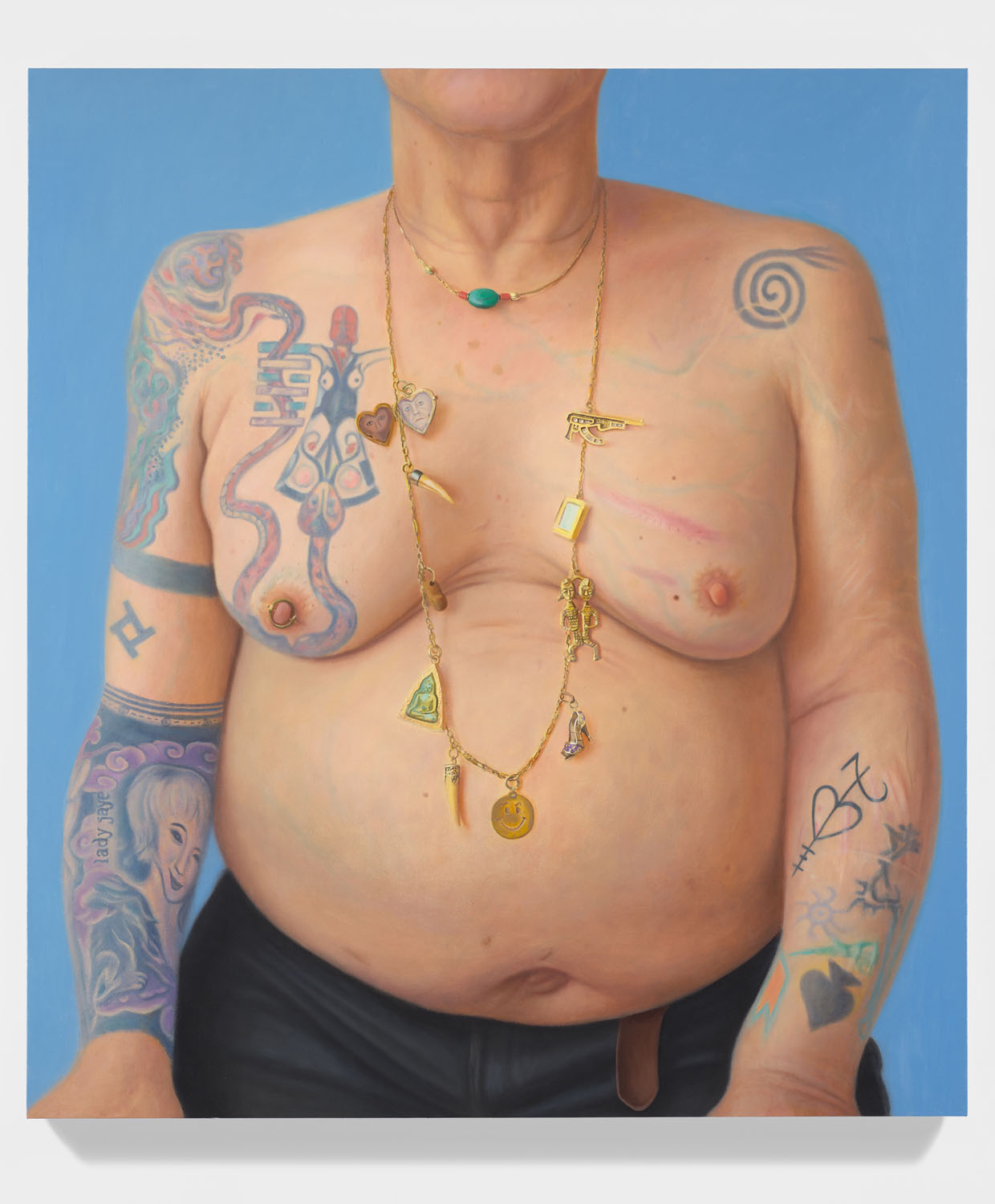

Sarah Thornton is a sociologist and author, most recently of Tits Up, a tome charting the place of women’s “top half” in the cultural sphere following the writer’s own double mastectomy.

What’s one thing you hoped to capture in your selection of 10 works?

My selections focus on the tender and fleeting moments of our time on this planet. They are about the vulnerability and resilience of the flesh, whether it is present or ancestral. They evoke meaningful worlds of love and death.

What role do you think art plays in shaping the queer community, and its larger place in American culture?

I don’t know how much art “shapes” queer communities, but the art world has been more hospitable to queer people than many other social milieux. Also, art infiltrates the homes of the rich and powerful, spreading understanding. Good museums have community outreach and education departments that can have a significant impact on the perspectives of locals and tourists. I wish this show could travel to San Francisco, where it would find an enthusiastic audience.

Sharmistha Ray

Artist and professor Sharmistha Ray pushes at the bounds of abstraction in their work across painting, drawing, sculpture, and more—shown at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Museu de Arte de São Paulo, and Fashion Institute of Technology, to name a few.

What role do you think art plays in shaping the queer community, and its larger place in American culture?

Art plays a profound role in shaping queer community by visualizing identities and experiences that have often been marginalized or erased. It creates spaces of recognition and solidarity, offering languages of embodiment and desire that exceed normative frameworks. Within American culture, queer and feminist art continually pushes against entrenched hierarchies—cultural, political, and spiritual—inviting viewers to see difference not as division but as expansion. These works function as acts of resistance and renewal, helping to define a collective imagination that is inclusive, fluid, and transformative.

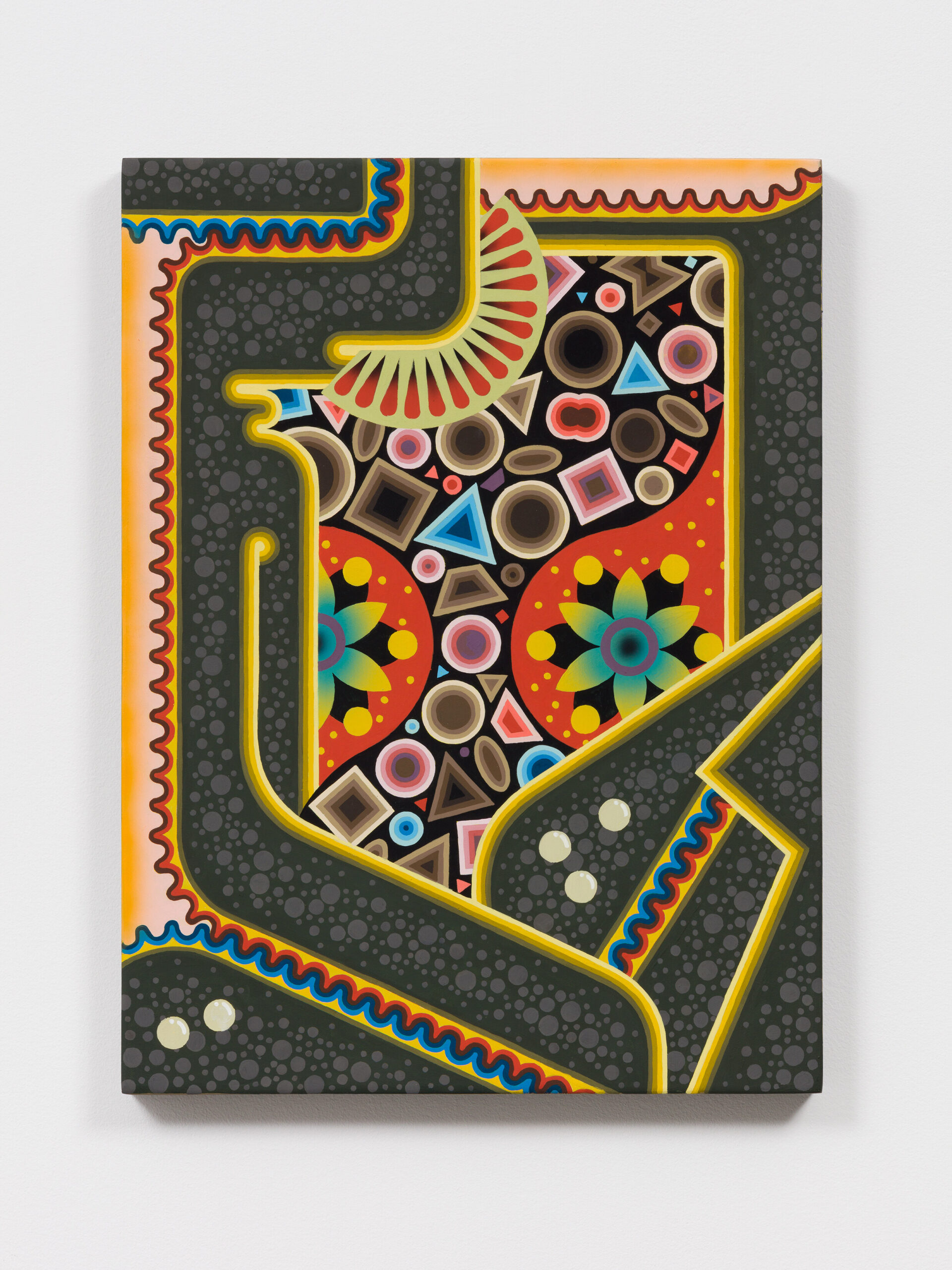

Is there a piece from the canon of LGBTQ+ artists that helped shape your work? How do you see it in conversation with your selections here?

I am interested in artists that use abstraction as a way to subvert the body fetish that so often characterizes an interest in queer art. Genesis Breyer P-Orridge’s body of work has been especially influential in thinking about art as a site of transformation and spiritual rebellion. Their creation of Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth embodied a radical synthesis of performance, ritual, and collective consciousness—a gesture that challenged binaries of gender and identity. I see this same spirit of radical spirituality and self-invention echoed in the works of Leilah Babirye, who reclaims queer identity through discarded materials, and in Edie Fake’s architectural comics, which map queer embodiment through layered visual and linguistic codes. Together, these artists use art as a means of remaking the self—and, by extension, the world.

in your life?

in your life?