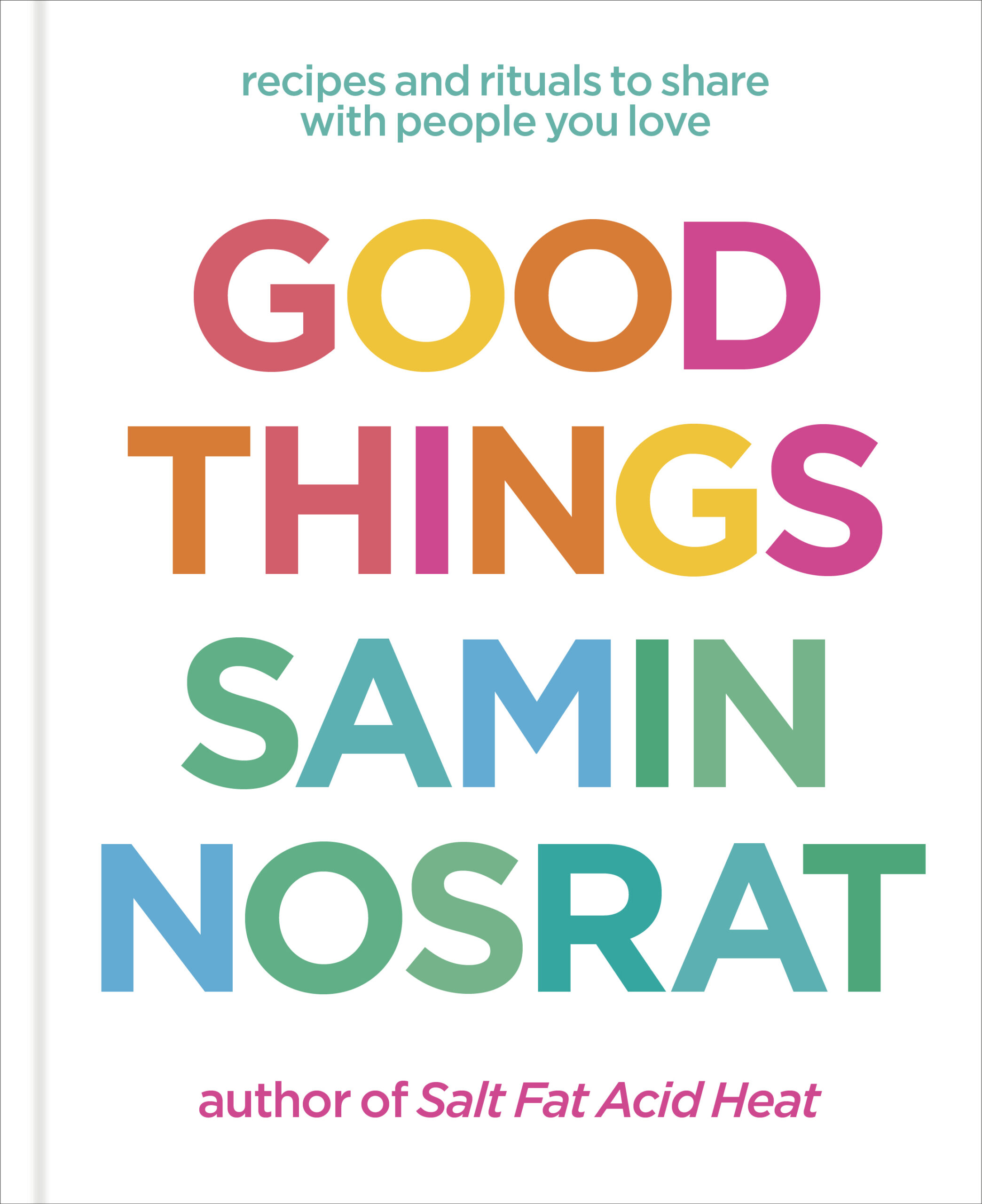

In Samin Nosrat’s highly anticipated second cookbook Good Things: Recipes and Rituals to Share with People You Love, her greatest goal was not to make a book filled with amazing recipes (although there are more than 125 of those). It was making the importance of gathering around the table the most meaningful takeaway.

In our conversation, we dove into big ideas, like whether cooking can be a radical act in a society where big tech is harvesting our attention for profit. (We landed on yes.) We also compared notes on how to cook for a crowd (work backwards and bring an emergency satchel of lemon, olive oil, and salt) and why it’s okay to fry in olive oil.

Nosrat offered so much useful cooking advice in our interview that it’s worth reading twice just to commit her advice about how to properly salt beans to memory. At the same time, her reflections on the intersection between food and society remind us why what happens in the kitchen never stays there.

CULTURED: Where are you, and what’s in your system?

Samin Nosrat: I’m in New York, and what’s in my system is pie. I didn’t eat it today, but yesterday I, along with a bunch of other people, judged a pie contest where we tasted 33 pies.

CULTURED: Tell me about your new cookbook.

Nosrat: I struggled with this book a lot. I wondered if I would be able to weave meaning into a book of recipes and connect to a larger part of life. After eight years of the book being in my head, I get to talk to people and have their experience of my work reflected back on me, and through that, I’ve learned a lot about myself and the book.

For example, a few nights ago I was in Iowa City, and [the writer] Carmen Maria Machado and I were talking about how cooking can be a radical thing. She said, “Do you really believe that? Things are falling apart around us right now. Do you really believe cooking is enough?” I thought, Well, I don’t think cooking is enough, but they are making money on our attention. They create social media to suck up our brain cells and our time, and then they sell the data they harvest from us to make money. Reclaiming our attention from these forces is actually quite radical. Not everyone has to cook. We can all find our own ways to ground ourselves and connect to other people. But cooking is my way, so that’s what I write about.

CULTURED: What’s your earliest memory of food and interacting with it?

Nosrat: I was very small, probably 3 years old. My mom was cleaning the house, and she lifted a couch cushion and underneath she found a piece of pepperoni pizza. And she was like, “Why did you put this here?” And I was like, “Oh, I was just saving it for later.”

CULTURED: Mine was that we would come home late at night and my grandma would make me fried eggs and french fries. She would fry everything in olive oil.

Nosrat: That’s very beautiful. But why were you coming home late at night as a child?

CULTURED: We would be at my cousin’s house until late at night. Every Greek child stays up late and is underslept. I’m very excited to ask you the next question: Do you ever fry in olive oil?

Nosrat: All the time. When I lived in Italy, we fried everything in olive oil. If you’re a careful cook, it’s completely in the zone of safety. A lot of it has to do with expense—which is why it’s not more customary here—but I wouldn’t be surprised if part of the reason that we use all these other oils is that there’s a huge agricultural industrial complex growing all of these plants and seed oils, so that is what becomes the fry oil. I also just saw Sohla [El-Waylly, a recipe developer and chef] on her Instagram talking about deep frying in olive oil and how it’s fine. So I’m like, If Sohla said it, it’s fine.

CULTURED: Tell us about adding salt to the cooking water of beans from the beginning rather than the end.

Nosrat: I understand how one could draw the conclusion that salting a bean would make it tough, because there are so many other things making it tough. Salt can draw water out of things and make them tough. But for beans in particular—and for anything dried that you’re cooking in water—that’s not true.

It’s in fact all of these other factors that make beans tough—including hard water or, even like moderately acidic water, which is why it’s nice to alkalinize your water with some baking soda. But if you use too much? Then the skins fall off, which is the trick that people use when they’re making hummus.

We would cook our fresh shell beans with olive oil and herbs and put in some tomatoes. I stopped putting the tomatoes in early because I don’t want to risk adding any acidity in the water. I’ll always add anything acidic or dressed with vinegar after they’re fully tender.

CULTURED: For me, Thanksgiving looked like spinach pie and lemon chicken. What did it look like for you?

Nosrat: We never had it. It was just a few days off from school. When I was maybe in 12th grade, my little brothers—my brothers are twins, they’re four years younger than me—felt left out. My mom bought a readymade dinner from Whole Foods. That was the first time we ever had Thanksgiving, but we did not sit down and enjoy it in any sort of cornucopia way. We were just eating some turkey with cranberry sauce.

CULTURED: It wasn’t depressing per se, it was just nonexistent.

Nosrat: Thanksgiving is a time of year that I just am very aware that I’m not a white American. It’s interesting because it’s not that rare to be a third culture kid, or a kid of immigrants, and there are of course different ways that immigrant families approach assimilation. Some people fully take it on, some people joyfully hybridize the traditions.

One thing I have not seen represented in the narrative or pop culture is this reluctant assimilation: I’m doing this because I feel I should, but I’m not happy about it.

CULTURED: Tell me about how you cook for groups of people. What salad do you make for a crowd? Do you have a sit-around salad recipe?

Nosrat: I try really hard to think about who’s coming: what do they like to eat, are there children, or vegetarians? I also want to factor in how much time and energy I have to give the meal. Things based on grains or beans are sit-around salads—the kinds of salads that improve with time sitting around being dressed. I absolutely would make a leafy salad for a potluck or a gathering and then dress it at the last possible moment.

Fifteen years ago, I was invited to a potluck book event for Deborah Madison. Everyone was bringing something—it was one of the first things with notable people that I was invited to. But I also had no money, and was working full-time. I scrounged through my pantry and found a bag of beans. I cooked the beans and made a super simple salad with crumbled feta cheese, some toasted cumin, some macerated onions, and olive oil and vinegar. I brought it and everyone was like, “What is this?” There wasn’t anything special about it, but I was shocked that all these luminaries thought it was so good. They kept asking for the recipe, and that always stuck with me—you guys are cooks, what do you mean “the recipe?”

CULTURED: Simple is best. You just make it right and it is delicious.

Nosrat: I also feel like the main problem of potluck food is that people make things that should not be sitting around all day. The only pasta that’s appropriate for a potluck is lasagna because it actually improves with cooling down a little bit and sitting. Anything else will just congeal and get gross. I always am thinking about the constraints of the final serving situation, whether it’s an office, kitchen, or park. Then I work back from there. Always have your emergency satchel of olive oil, lemon, and salt.

CULTURED: Kitchen utensil or tool you use the most?

Nosrat: The little Y-shaped vegetable peeler. I use that every day.

CULTURED: Breakfast, lunch, or dinner, and why?

Nosrat: Lunch has been my favorite for a while. First of all, I’m 46 now so digesting takes a lot of my day and energy and there’s just a lot more possibilities involved in lunch. I don’t want to have long dinners anymore. 5:30 p.m. is my ideal dinner time.

CULTURED: What do you never do in someone else’s kitchen?

Nosrat: Don’t open someone’s fridge unless they say it’s okay.

CULTURED: Can you draw a parallel between your relationship to food and a way of looking at the world?

Nosrat: Being in the world is about adapting to whatever you are given—weather-wise, environment-wise, social-wise. You have to adapt in real time to the life experiences as they appear. That’s absolutely how I think about cooking. I have an idea that I really want to make something with tomatoes today, or cook out of my garden—and then real life happens. Where people go wrong is holding too tight to the original plan. That’s where the friction comes from.

in your life?

in your life?