I’ve never really had FOMO, except when it comes to Francis Kurkdjian. Over the years, I’ve heard about the perfumer’s artist collaborations. First there was L’odeur de l’argent, back in 1999, for artist Sophie Calle. I desperately wanted to smell it. I couldn’t imagine Kurkdjian, the king of modern perfumery, creating anything but something beautiful and wearable. Would it be a crisp, efficient cologne, as bright as a brand-new dollar bill? Would it be metallic, deep and charismatic, like an old darkened wheat penny?

For his 2007 PréamBulle, he flooded the gardens of Versailles with a shimmering blizzard of delicate bubbles, each scented with strawberry, pear, or melon—favorites of Louis XIV. Did the pop of each bubble release the scent of an individual fruit? Or did they meld together in a juicy accord?

And then there was 2012’s L’or bleu, the drinkable perfume water that he formulated with artist Yann Toma, inspired by the 14th-century perfume tonic known as “The Queen of Hungary Water” and the methylene-blue-laced cocktails served by Yves Klein at his 1958 “Le Vide” exhibition. (Klein’s guests urinated blue for days after.) Is L’or bleu actually drinkable? Is it something like fresh cucumber juice, where the aroma and taste align? Or non-synchronous like coffee or dark chocolate? Is it blue? Does it taste blue?

All questions were answered last week at “Perfume: Sculpture of the Invisible,” a Kurkdjian retrospective at the Palais de Tokyo. Running through Nov. 23, the exhibition, curated by Jérôme Neutres, celebrates 30 years of Kurkdjian art, from his collaborations with photographers, chefs, and musicians to his infamous site-specific happenings at cultural monuments around the world.

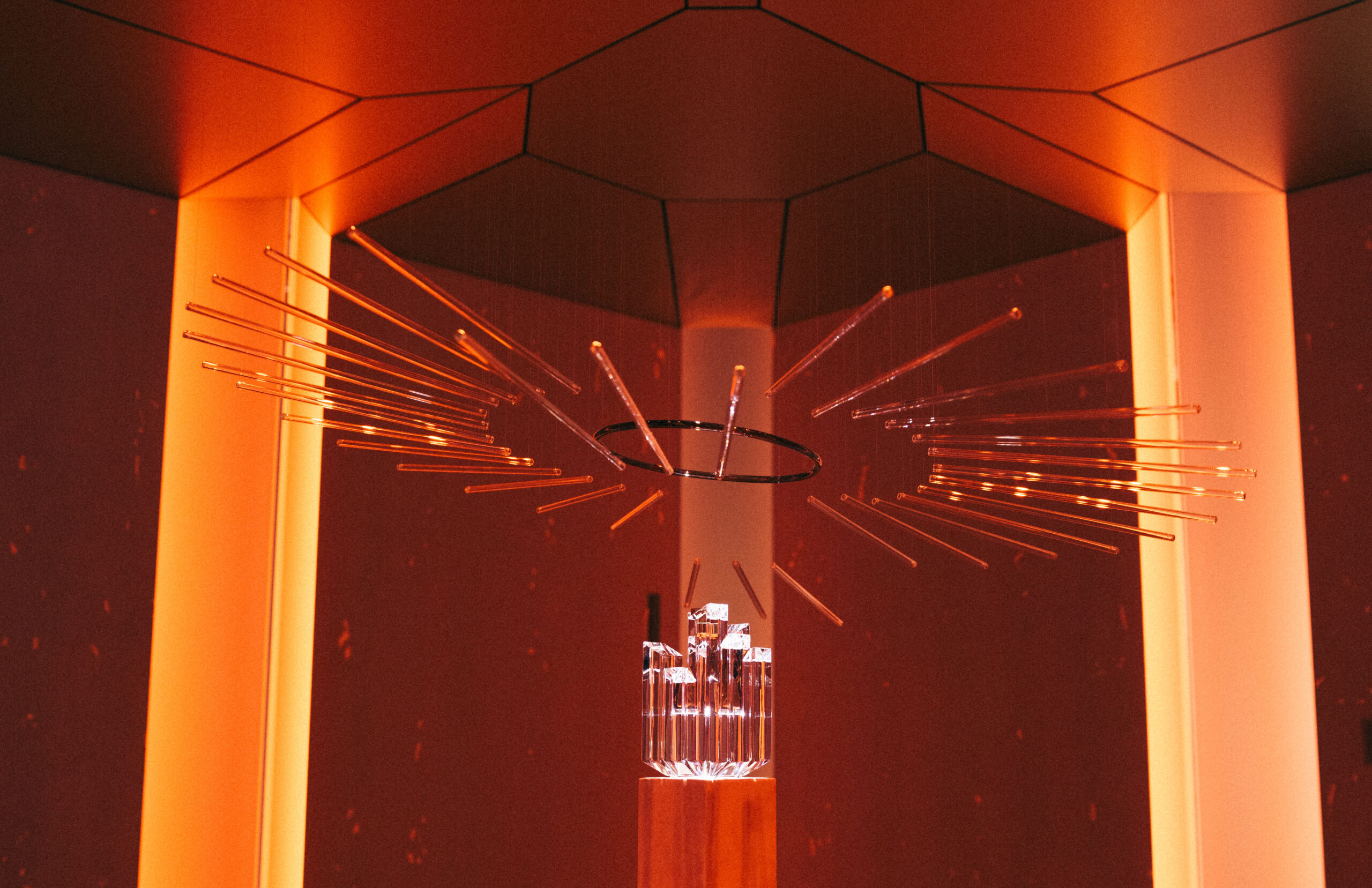

A few works are on display for the first time: In L’Alchemie des sens, Kurkdjian’s friends—artist Elias Crespin, pianists Katia and Marielle Lebèque, composer David Chalmin, and director Cyril Teste—team up to translate Kurkdjian’s Baccarat Rouge Édition Millésime (only 54 bottles are available each year) into an immersive experience touching each of the five senses. (There’s chocolate involved!) Calle sent over bags of material from her personal archives; during Kurkdjian’s remarks at the opening, she stood on tip-toes in the middle of the crowd, waving her arms in the air. Musician Kilo Kish flew in from New York. “The past does hold keys, processes, and ways of being that could potentially be lost without drawing those connections into the future,” Kish says. “I’m inspired both to try new things and to collaborate in new ways, as well as study the histories a bit more.” Kish’s personal favorite of the 40-plus scents on display? The rich, velvety tuberose Opening Night, composed for Isabelle Adjani in 2019, when she starred in Cyril Teste’s stage adaptation of John Cassavetes’s film.

At perfume school, Kurkdjian and his fellow students were all told that they were artists. “Because many perfumers think that what they create is art,” he says. “But I am lucky in that my parents gave me an artistic education, so before going to the perfume school, I knew what being an artist meant.” Kurkdjian’s grandparents would take him to the Louvre all the time. Everyone in his family plays a musical instrument. He started ballet at the age of five, eventually performing with Compagnie Versailles Soleil. “Art is all of the aspects of life. Art is about finding the beauty in death. If you think about Goya, art is about feeling pain. When you listen to music, art is about all of the emotions. Art is not just one spectrum of feeling. Art has no boundaries, no limits on self-expression,” he says.

According to Kurkdjian, commercial perfume, on the other hand, has very defined boundaries. “The way the perfume world sees the world is a very narrow window where everything is beautiful,” he says. “Literally beautiful, in a very normal way. All the women and the men are just beautiful. They all drive beautiful cars. They all are happy every time. They all find love. Perfume, unfortunately, usually shows a very narrow spectrum of life, an ideal life. The perfume world just shows paradise.”

Within this paradise, Kurkdjian has excelled, winning fragrance awards and breaking sales records. He’s launched over 300 scents over the past 30 years, from his first blockbuster, Jean Paul Gaultier’s Le Male in 1995, to ethereal works for Christian Dior Parfums, where he has been the Perfume Creation Director since 2022. At his own maison, he has redefined paradise with complex, polarizing creations such as his wildly popular Baccarat Rouge 540 (currently TikTok’s most searched beauty product).

Kurkdjian credits Calle with pushing him out of commercial perfume’s safe, pretty paradise. “She opened the door to abstraction. She opened the door to something totally out there. She opened the door to the world of linking art and smell together. I owe her all of that,” Kurkdjian says. “Sophie is the one who brought my consciousness to another aesthetic level.”

“Perfume: Sculpture of the Invisible“ spotlights Kurkdjian’s more challenging scents, such as the aggressively melancholic Courante—created by Kurkdjian and cellist Klaus Mäkelä for a 2022 performance of Bach’s “Cello Suite No 2.” One museum-goer said that it felt like “a punch to the nose.” And as for the Calle x Kurkdjian scent of money? While the notes seem benign—linen, ink, and basmati rice—the final composition is far from innocuous: it smells uncomfortably warm, sticky, and oily, like the body odor of a stranger. After smelling it, you’ll feel itchy. You’ll feel like you need to wash your hands.

L’or bleu, however, is pure delight. At the installation, the clear water (no methylene blue here) is served in paper cups. The recipe, hung on the wall, promises, “This magical and beneficial water will bestow the finest artistic energies on whomever drinks it.” It is addictive—light and fresh, super invigorating, with hints of citrus, rosemary, and spearmint. Over the course of the hour, I went back for a second and third cup: the first two, I drank straight away, the third I splashed on my wrists and neck. I would buy gallons of this.

L’or bleu tastes cool and sparkling, yet, physically, it’s neither cool nor sparkling, a magic trick created via the power of aroma. When teaching, Kurkdjian hands out bags of Haribo Tagada. He’ll ask students to plug their noses “really tight, so no air gets in,” place the treat on their tongue, and then chew for three seconds. “Really pay attention to the flavor, to the texture,” he says. The treat tastes flat—sweet and white, generic. At four seconds, he’ll instruct you to “free your nose” and take a breath. A candy-bright flood of red strawberry will hit your mouth with such force that you’ll see pink. For the rest of your life, you might never see a tagada without thinking of Kurkdjian.

For his VR experience Ėden, Kurkdjian developed V-scent, a device that attaches to a traditional VR headset to release timed aromas. Wherever you “look” while wearing the scented VR headset, you’ll grow a new, mysterious plant or tree or fungi, each releasing a unique odor—some ominous and others ethereal—and each, like the flora that they belong to, both strangely familiar yet completely new. You might, unaware, brush up against the IRL gauze curtains that enclose each viewing cabine, and feel as if your garden has reached out into the real world to touch you. That’s the magic of Kurkdjian: he brings the surreal into the real world and makes the real world feel more surreal.

The culmination of the visit is a recreation of Kurkdjian’s office—on the walls, his art; at his desk, paper blotters and glass vials and, intermittently over the four weeks of the exhibition, Kurkdjian himself. On my visit, he was answering emails. During other “work hours,” he will tinker with Variation pour Sophie, a brand-new fragrance being created on site for Calle. A lifelong perfume lover who wears scent everyday, Calle told Kurkdjian that “perfume dresses her just as clothing does, and that she can’t imagine leaving her house without it.” She challenged Kurkdjian to create a new scent that would “synthesize” those that she’s loved the most: Kurkdjian’s own Grand Soir, Guerlain’s Habit Rouge (created by perfumer Jean-Paul Guerlain in 1965; updated by perfumer Delphine Jelk in 2024), and Molinard’s Habinita (created by perfumer Henri Bénard). As the formula is updated throughout the month, Kurkdjian will sample the latest version via unlabeled blotters in the back of his “office.”

On opening night, version one of Variation—a seductive warm, smoky amber—was already a hit. Guests were going back again and again for the blotters, tucking them behind an ear or in a lapel. At the opening, I asked Calle for her opinion of this first iteration of Variation pour Sophie, but she replied that I was too impatient, that the perfume wasn’t finished yet, and that she wouldn’t be able to give me her opinion for another four weeks.

in your life?

in your life?