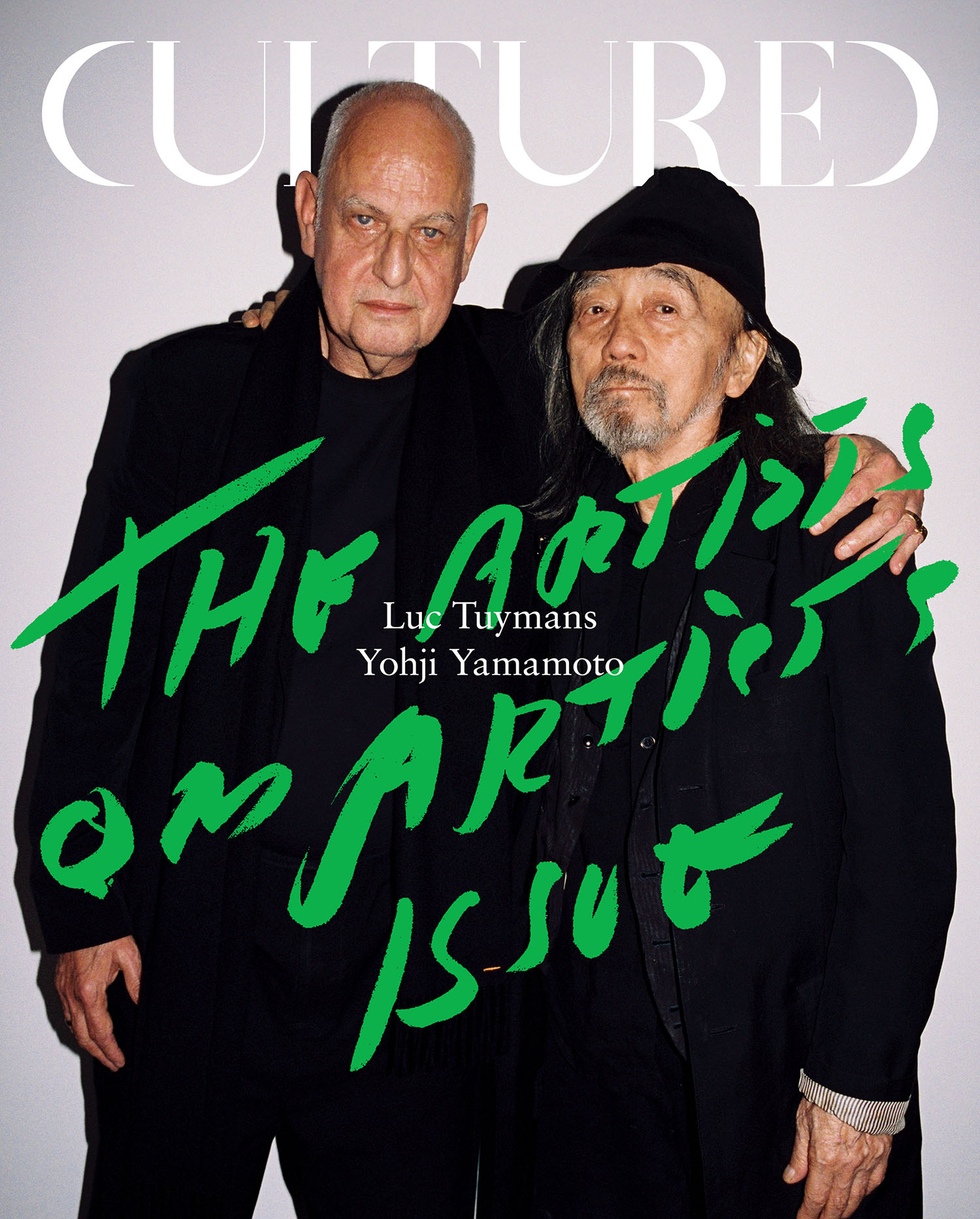

Luc Tuymans first met Yohji Yamamoto on a visit to Japan with his wife, the Venezuelan artist Carla Arocha, in 1999. The Belgian painter had opened his debut exhibition with David Zwirner in New York a few years earlier. He was fascinated with the Japanese designer’s simultaneous precision and undone ease—qualities evident in his own politically oriented paintings.

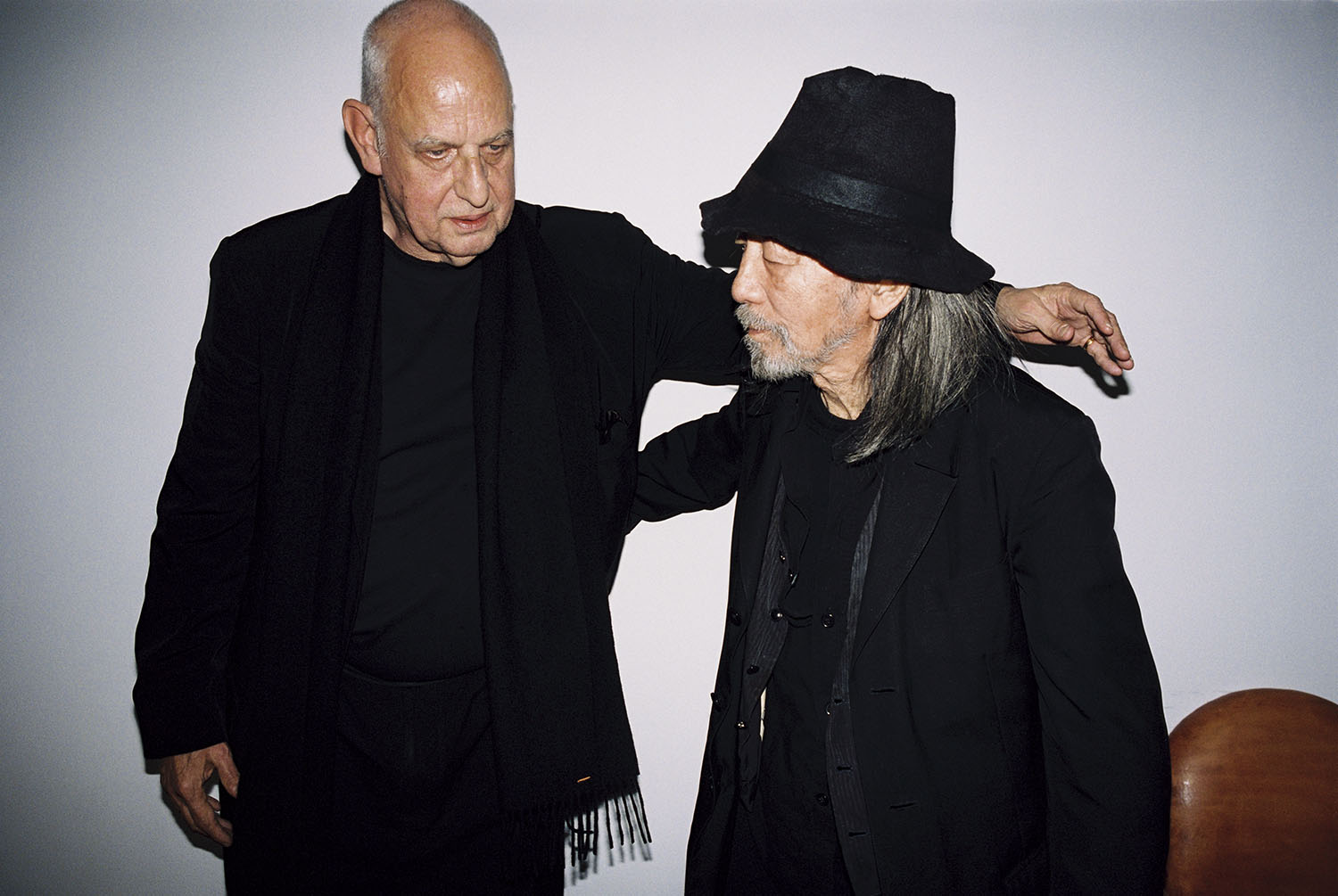

Who could have predicted that, more than 25 years later, the two men would still be friends, savoring simultaneous career milestones (at 82, Yamamoto’s business is generating more than $200 million a year; Tuymans, 67, opened a show of large-scale works, his 18th with Zwirner, in New York this November). Just days after Yamamoto debuted his Spring/Summer 2026 collection at an October Paris Fashion Week show Tuymans attended, the pair reunited at Yamamoto HQ for a cigarette and a chat about anger, black clothes, and cowboys with their frequent sparring partner, the writer Donatien Grau.

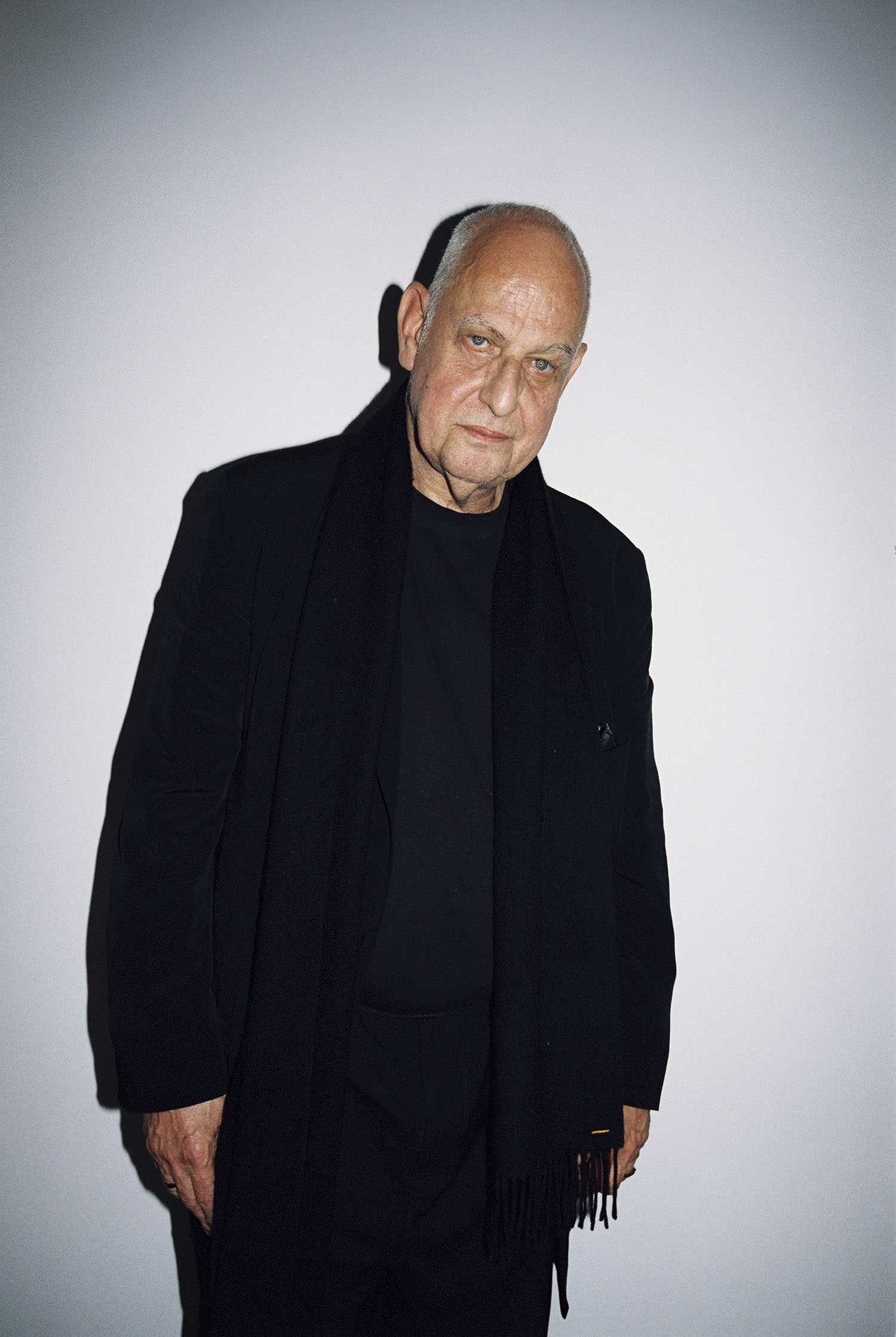

Luc Tuymans is not just a great artist, he is also a great Yohji Yamamoto fan. He follows a kind of uniform, always in black—as if colors belong not in life but in art. It makes sense, then, that he would appreciate the work of a designer who, for nearly 50 years, has aimed to make black the greatest color for clothes.

The presentation of Yohji Yamamoto’s Fall/Winter 2025–26 menswear collection in Paris last January featured a number

of artists on the runway: Yohji-san invited Luc to lead the group, and he immediately agreed. He did not do it for any other reason than care and admiration. Yohji-san was so moved by his presence during the fittings—as well as that of his wife, artist Carla Arocha—that he asked them to walk the show together, a celebration of their commitment and love.

Eight months later, toward the end of September, I visited Luc at his Antwerp studio and home. He told me, in his nonchalant

way, that CULTURED had asked him to do a conversation with Yohji Yamamoto. Immediately, themes for their dialogue started spinning in my head: their attachment to place—Antwerp for Luc, Tokyo for Yohji— the role of medium, the importance of rebellion and critique, and of course, anger (where we started our conversation). I told Luc that I would love to be their sparring partner; Yohji-san was up for it, too.

This brings us to an upstairs room at the Yohji Yamamoto offices in Paris, on an early October afternoon just two days after the designer’s show, which Carla and Luc attended. We sat for a conversation that could have lasted hours—a very beautiful, moving moment, in which a deep understanding emerged between two of the greatest artists of our time.

Donatien Grau: Both of you make work that contains a lot of anger, which you manage to transform into brilliance. I would be delighted if you could tell me about your first memory of anger.

Yohji Yamamoto: My life started from anger. My first anger was at the age of 3 years old. My mother told me, “Your father was brought to the war.” Two years before the war ended, he was taken to the army on a boat. My father [wrote her to say] that, because he had been given a warm-weather uniform, maybe he was being sent south. This was his last message, in 1945. Can you imagine?

When I was 5 or 6 years old, my mother showed me the report of how his life ended. It was written on a small piece of yellow paper that he died [while his boat was approaching] Manila. He never arrived. I got so angry at the Japanese government, at the army.

“Both of you make work that contains a lot of anger, which you manage to transform into brilliance.” —Donatien Grau

Grau: Do you have a childhood trauma or anger, Luc?

Luc Tuymans: My parents’ generation also came up during the war. Both my parents lost brothers. My father got a phone call way later, when I was not living at home anymore. He went to answer the phone out in the corridor, and when he came back, he was very distraught because somebody had finally explained to him how his brother, who had been killed during the war, actually died. It was shrapnel wounds and things like that.

Our family was in two camps. My mother was Dutch, and there was the Resistance. My father was Flemish, so there you had a complicated history of collaboration. During dinner, it was always a fight. My sister and I would eat very fast just to be away from the table. I got angry about that—not at my parents, but at the rest of the world, or the outside, let’s say. That may be where this phobia with the idea of the war came from.

Grau: These moments of anger have stayed with you; you can still feel them today. Some people just stay angry and can’t cope, can’t deal with their lives. But you have managed to make something from that anger, and that thing is your work. Can you tell me about that?

Yamamoto: I was a young kid, angry at my own government, thinking that they were lying. I thought I was going to do something violent, that I’d end up in prison because I couldn’t accept this big lie. During that same time, my mother decided to study how to make clothing for three years. So she sent me to my grandmother and great-grandmother’s country house far away. By the house, there was a river, a mountain, and the sea. The two of them would watch me play in the water; they were so sweet. Even now, I would like to go back to that moment.

Grau: It seems that first there was anger. Then, thanks to your mother, your grandmother, and your great- grandmother, it was transformed by discipline and love. That could be considered a definition of you.

Yamamoto: That’s true. Two years after that, my mother visited us. She looked like a beautiful modern woman from Tokyo. I couldn’t talk to her. I felt like, Who are you?

Grau: Luc, a lot of your work also deals with anger, discipline, and in more subdued ways, love.

Tuymans: I was bullied in school because I was silent, skinny, blonde, and blue-eyed—so I looked like the perfect student, but I wasn’t. Since my mother was Dutch, they shipped me to a boys’ camp in Holland in the summers. One day, on a huge square, there was a competition where 150 kids had to make chalk drawings. I won the yellow sweater. When I went up to the podium, I thought, This is what I can do to be accepted. Not that I knew what an artist was—I just felt that I had an ability.

Yamamoto: When my mother brought me back to Shinjuku, I was a primary school student and I was studying Kendo. I remember one day practicing some moves, and I accidentally hit an American soldier. He didn’t get angry with me, and suddenly I started liking the American army. The American soldiers had been our enemy, but this particular one didn’t get angry at me. Around the same time, I remember playing catch with my friend, and the ball hit a very beautiful car.

It belonged to the head of the Shinjuku yakuza. The driver got angry, and he shot at me. I was a kid! An American soldier hadn’t gotten angry at me, but a Japanese yakuza driver did. How do you feel when you hit this kind of occasion?

Grau: Luc, Yohji-san just told us about his ambivalent relationship to Japan and America. You also had a very early relationship to America.

Tuymans: When I first went, I was amazed by the fact that Americans were always so positive back then. That was endearing to me, because, where I come from, it was not the case. They have a great respect for the old culture that they came from. On the other hand, there was also a misunderstanding, to a certain extent.

Grau: Americans misunderstand your work?

Tuymans: Many Americans do understand the work, but in terms of feeling, in terms of the emotional context, it is different for them.

Yamamoto: When I was living in Shinjuku, a customer of my mother’s worked in a cinema. I started [watching] cowboy movies. At first, they looked so brave and nice. But after four or five films, I noticed that cowboys were killing the so-called Indians.

“When I first saw a fashion show, I was like, What! All this work for half an hour? My work is immobile; it has to be still, contemplated. Your work moves around in society.” —Luc Tuymans

Grau: It’s that ambiguity of who’s right and wrong, which is, Luc, central to your work.

Tuymans: Yes, but without the sense of moralizing—that is the worst thing. When you actually try to discern the fact—like you did when you found out about [your father and] the war—you find out that things are much more ambiguous. I was fascinated by power—not to have it, but to analyze it, to see how it functions.

Grau: Luc, you often use very subdued colors. You, Yohji-san, have said many times that black, because it is understated, is sometimes the greatest statement.

Yamamoto: When I started helping my mother make clothes, we had so many customers who asked her to make things from fashion magazines—all those pages were covered with colorful floral prints. I would look at the photos and at the customer. I thought, It would be impossible to make this clothing for that person. I began to hate colors and prints. I started to always wear a black T-shirt so as not to disturb people’s eyes, and I still do now. This is the moment when my work in so-called fashion started. At that time, black was not a fashionable color at all. It was worn at funerals.

“I started to always wear a black T-shirt so as not to disturb people’s eyes, and I still do now. This is the moment when my work in so-called fashion started.” —Yohji Yamamoto

Grau: But look at your Spring/Summer 2026 collection. You also love color.

Yamamoto: Not really. I only love Japanese red. Japanese women used to wear kimonos, and the final piece was red. Maybe I can bravely say that the most appealing colors are black and red.

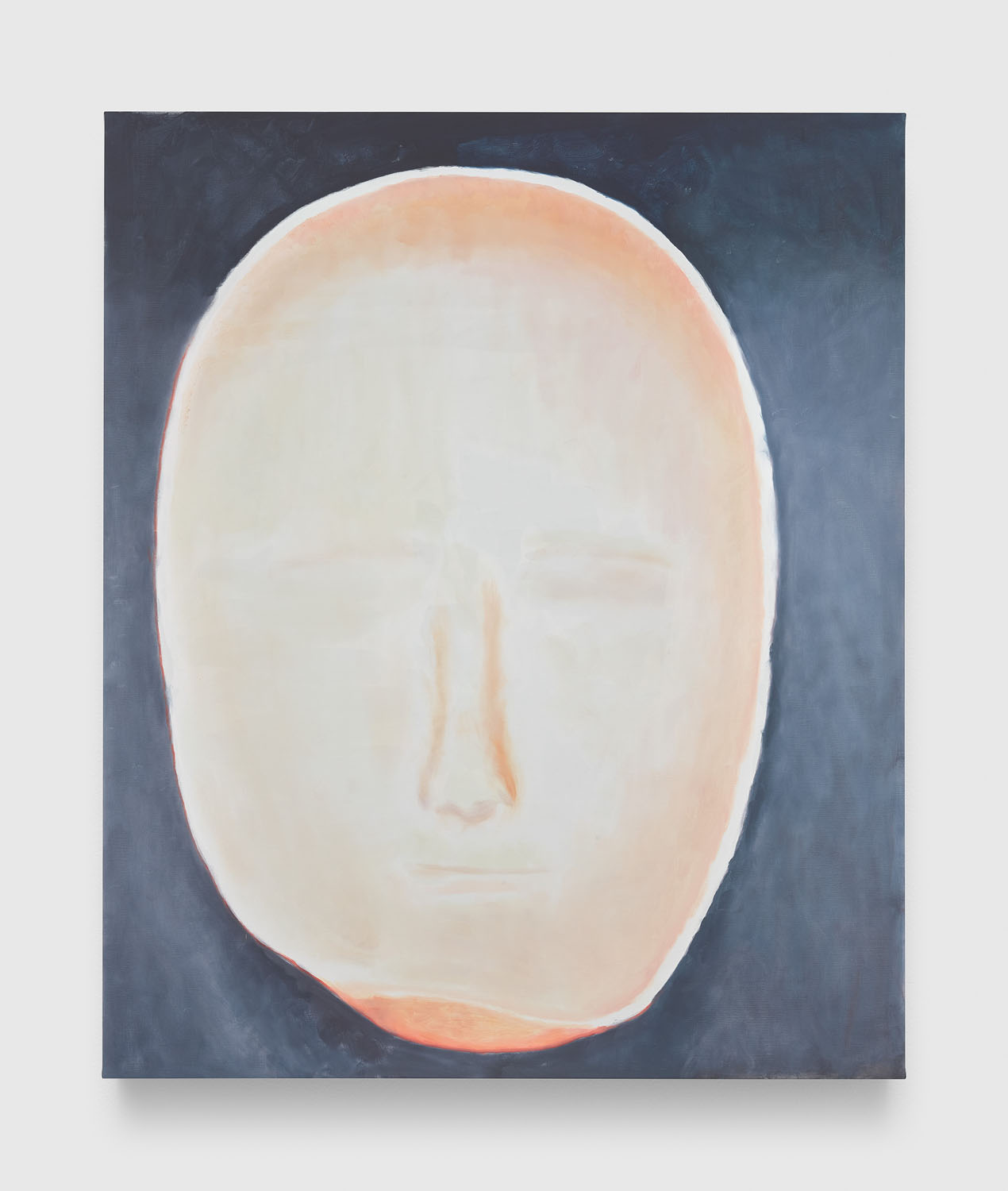

Tuymans: I started wearing black when I was 16, I think. Color for me is never straightforward. It’s about tonality, temperature. Flat color is like sculpture—there have to be layers. Now I work in a much more colorful manner, but it took me years to get the right contrast. I was always afraid to overdo it. Only a couple of years ago did I finally dare to play more with contrasts. Probably because I’m a bit older now.

Grau: Luc has thought a lot about what he wanted to discuss with you, Yohji-san, and has all these ideas. Luc, I would love for you to say what you’ve been thinking about in relation to Yohji-san.

Tuymans: The most interesting thing in Mr. Yamamoto’s work is the detail and the disregard of detail—a complex situation which is, on the one hand, very Japanese, and on the other hand, not at all.

Grau: Very Flemish, too.

Tuymans: Yes, it’s very close to where we actually meet.

Grau: Do you agree with that, Yohji-san?

Yamamoto: I’m sorry to say, it’s only a technique to make people feel less bored.

Tuymans: That’s a good answer. I’m also fascinated by the deconstruction of the clothes, which was new when you did it. I have always had a great respect for designers. When I first saw a fashion show, I was like, What! All this work for half an hour? My work is immobile; it has to be still, contemplated. Your work moves around in society.

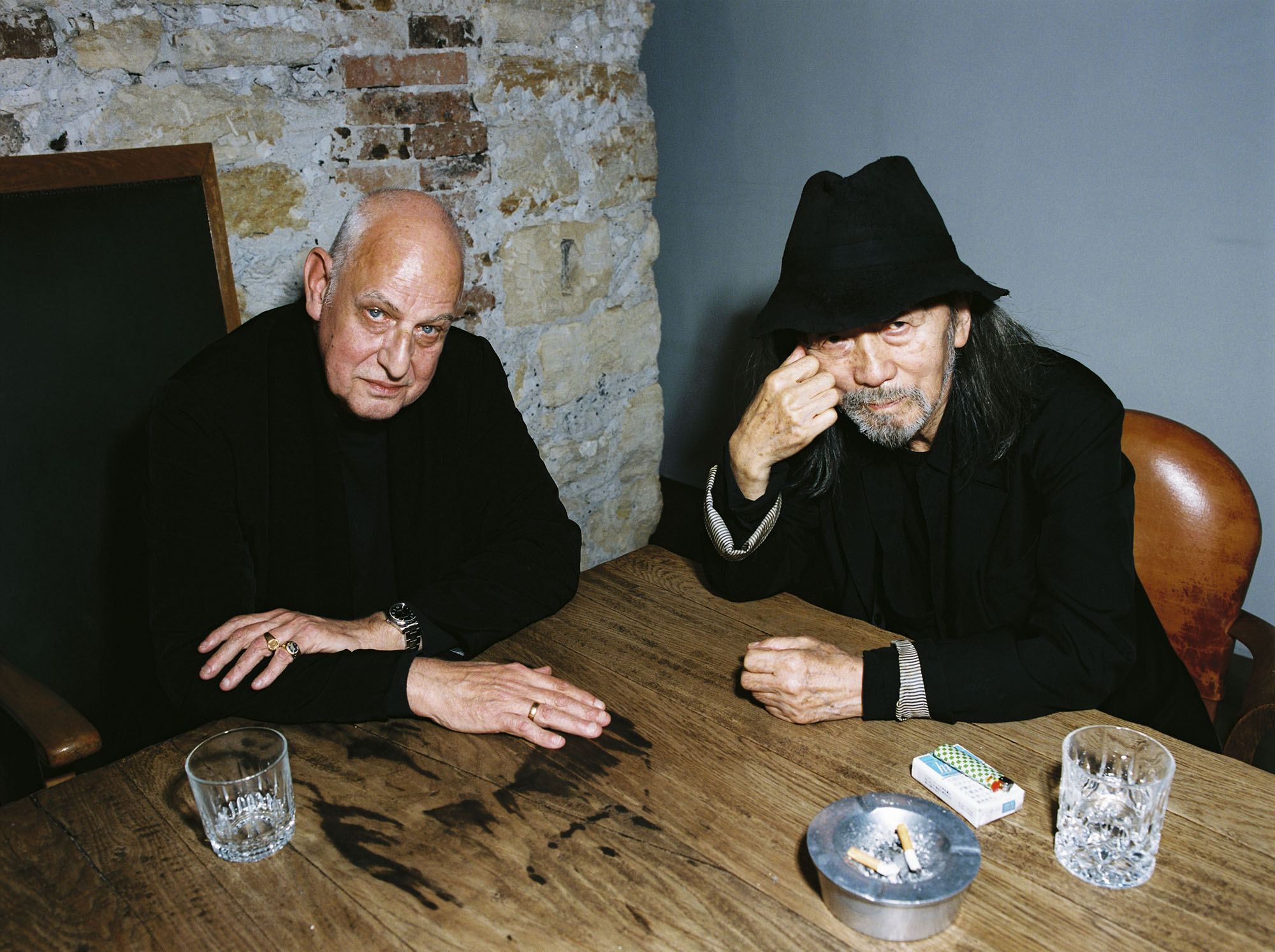

Grau: You are both passionate smokers. Luc, you wanted to quit, but can’t. You, Yohji-san, have never tried.

Yamamoto: I never thought about it.

Grau: What do you feel when you smoke?

Yamamoto: I started smoking cigarettes when I was 16 years old. I never, ever thought about stopping. I can die anytime. If I were to think about making my life longer, I would quit cigarettes. But I have never thought about that. Tomorrow, I can go up there or down there. But I’ll never stop.

Tuymans: It’s a way of transporting yourself somewhere else. Even though I tried to get rid of it, it keeps coming back because it is embedded in the work process. The dopamine slows me down, and gives me time to think.

Grau: My last question to both of you, Yohji-san and Luc, is: What can art do?

Yamamoto: Very often, art can make people feel braver or feel fantastic, but sometimes art can make people feel down, sad. It has this double power.

Tuymans: Art can make people reconsider, and maybe eventually think. It’s, in a very weird way, a distorted form of hope. And it’s a necessity in life.

You can purchase a copy of the Artists on Artists issue, featuring this conversation and many more, here.

in your life?

in your life?