On December 18, 1974, journalist Linda Rosenkrantz asked her friend, the photographer Peter Hujar, about his day. He told her about it, uninterrupted, for 74 minutes. Rosenkrantz had designs on a book project chronicling how artists spend their time. Ultimately, the book never came to pass. Hujar’s interview was the only one she conducted. The transcript of their conversation faded into obscurity until, decades later, a group of editors at Magic Hour Press plucked it from a collection of Hujar’s work and published it as a slim volume in 2021.

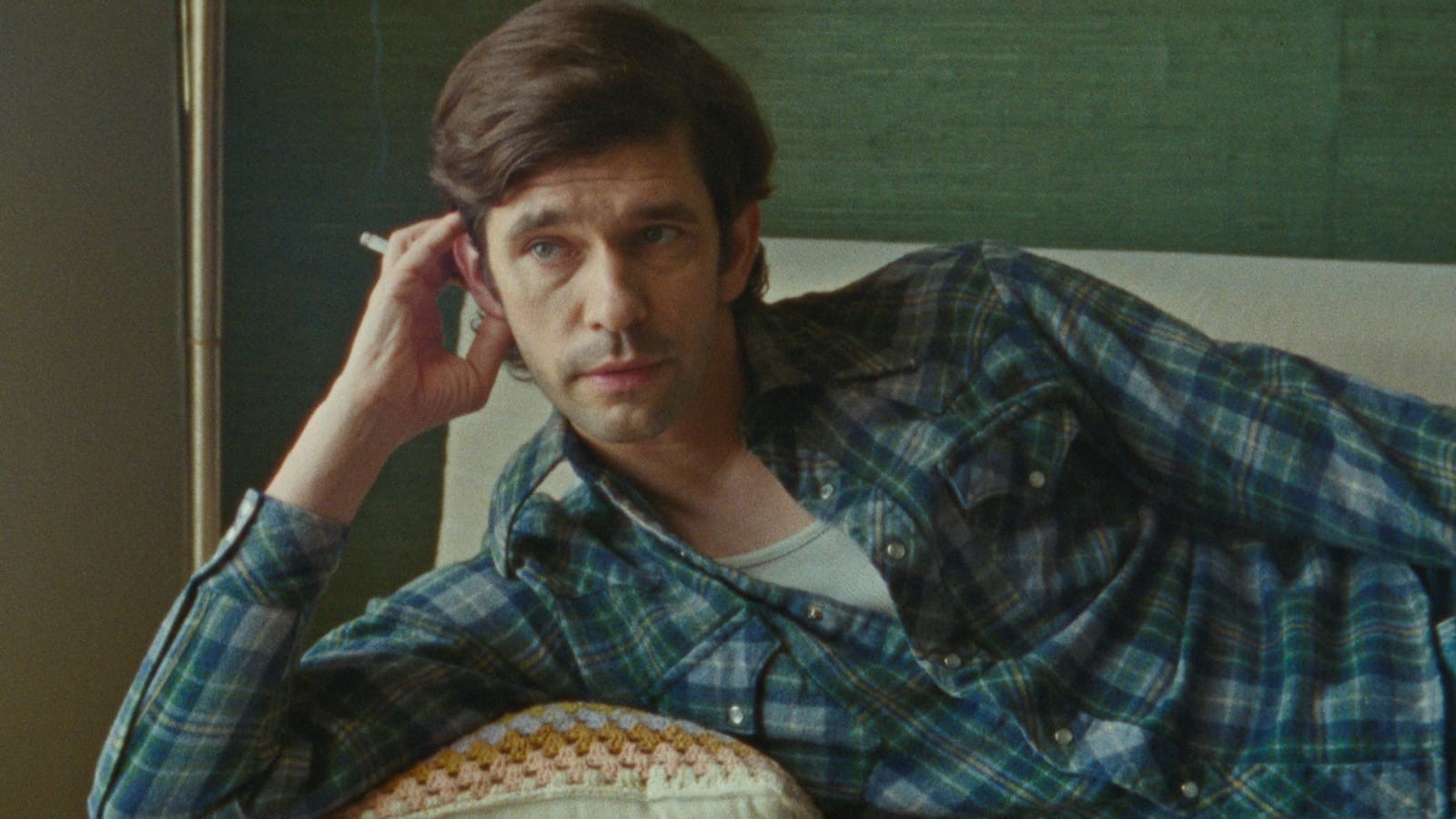

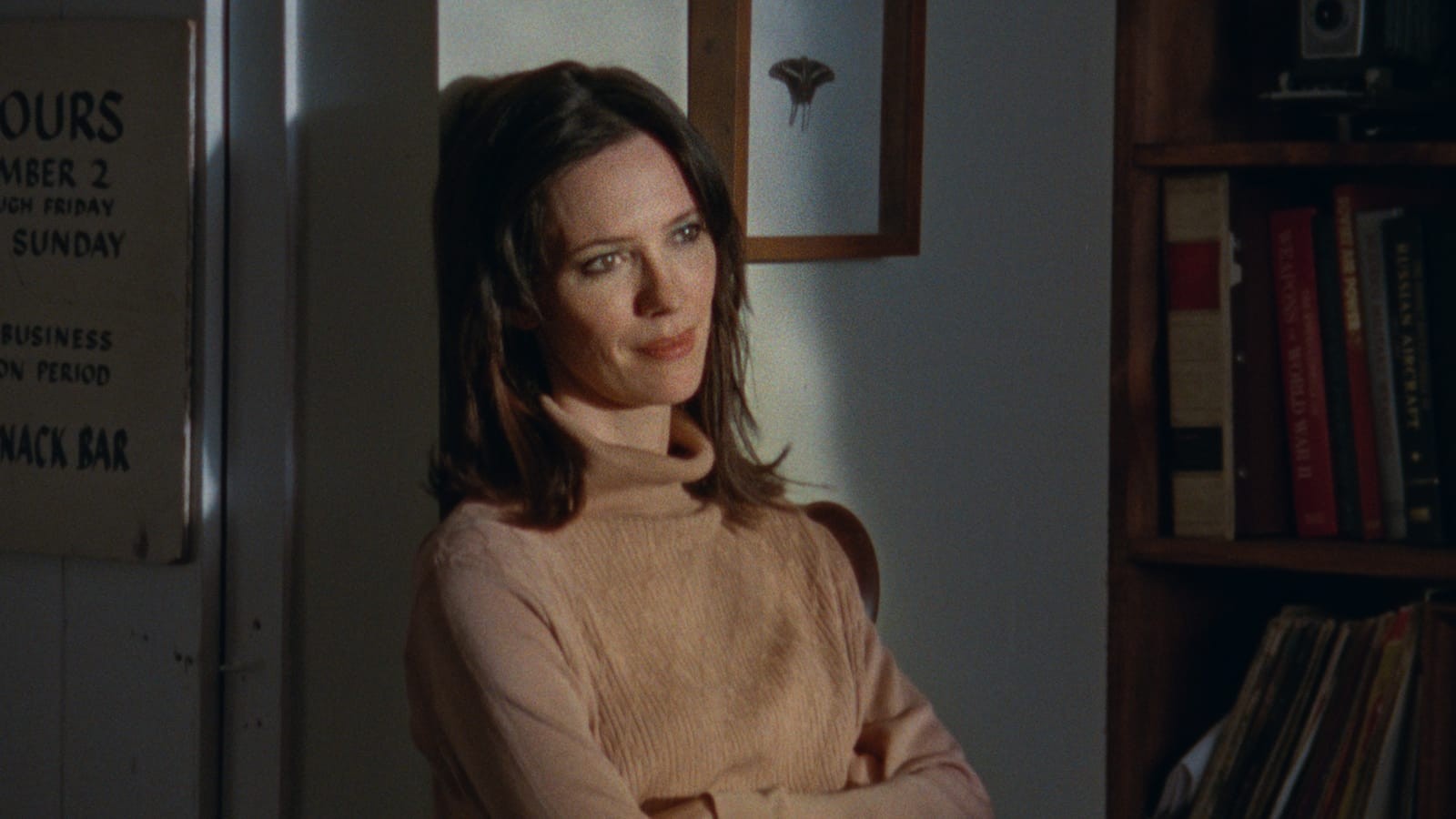

That conversation is at the center of Ira Sachs’s new film Peter Hujar’s Day, starring Ben Whishaw as the photographer and Rebecca Hall as Rosenkrantz. The film is a verité gem: It manages to paint a portrait of New York City’s lost downtown art scene without ever leaving the living room.

Shot at Westbeth, an affordable housing complex for artists in the West Village, Peter Hujar’s Day alternates between quiet domestic tableaux and the occasional Brechtian flourish. Sachs’s precise directorial eye finds elegance in the framing of every shot. He and cinematographer Alex Ashe photographed the spacious split-level apartment from various angles and times of day in order to create a robust visual language in a film that is largely dialogue. The actors make tea and eat cookies. They have a cigarette on the roof. They laze about, meet each other’s gaze, and drift off into reverie.

Then there’s the name-dropping: Hujar describes a phone call with Susan Sontag, a meeting with William Burroughs, an awkward visit from an Elle editor. Much of the runtime deals with a disjointed photo shoot Hujar did of Allen Ginsberg, his first assignment for the New York Times. Even though we never leave the apartment, the bohemian scene of mid-’70s Manhattan comes alive in Hujar’s tales of gallery intrigue and falling asleep to the sounds of sex workers chatting outside his window. The daily errata of life in New York also seeps in: waiting on commission checks from magazines, worrying about wearing the right coat, and having chance encounters at the bodega.

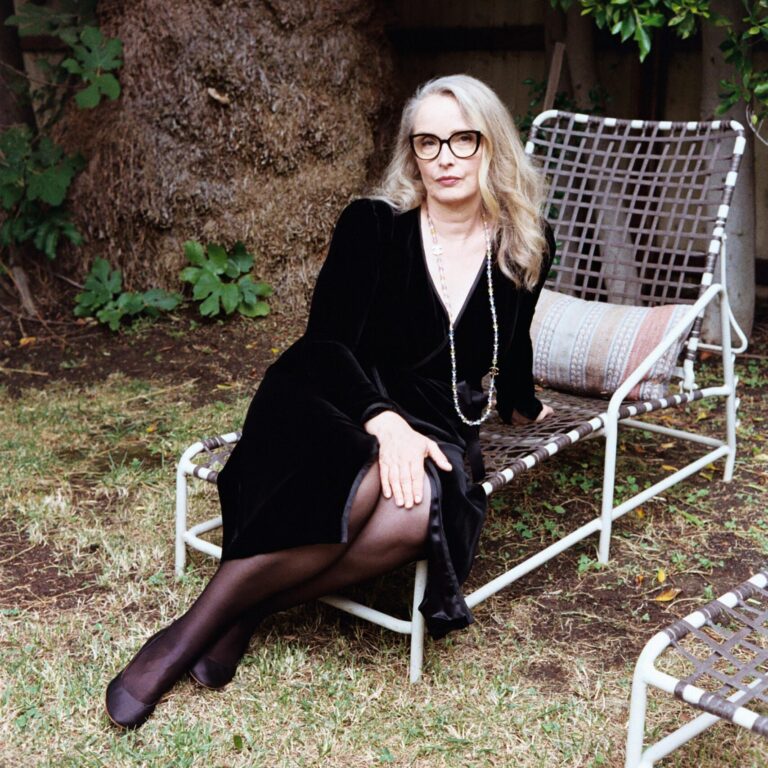

Nestled between Sachs’s 2023 roiling love triangle film Passages and his upcoming musical The Man I Love, Peter Hujar’s Day is smaller in scope and more modest in tone. But it gives new depth to three underlying forces of all of his films: process, intimacy, and curiosity. A few days after its U.S. release, CULTURED caught up with the filmmaker to discuss his relationship to 1970s New York, Elizabeth Taylor, and self-doubt.

CULTURED: I feel like I should ask you to recount your day yesterday in great detail.

Ira Sachs: I wouldn’t be able to do it as well as Peter Hujar. [Laughs] I recently finished shooting a film. I’ve been relishing the anonymity of not being a film director and not having the responsibility to come up with a series of ideas on an hourly basis, minute by minute. Somehow film directing has the challenge of what Peter does in the course of recounting his day: You have to be present. Now I get to be absent. And I’ve been seeing a lot of movies; I saw The Mastermind yesterday, which I liked.

CULTURED: That would be an interesting film to put in conversation with Peter Hujar’s Day.

Sachs: In terms of the period?

CULTURED: The period, but also in terms of an orientation towards process and attention and pacing.

Sachs: I would agree with that. They’re both process films.

CULTURED: They also both ask a lot of the audience in terms of attention. Peter Hujar’s Day follows a single real-time conversation. It also has so much to do with Peter’s attention as a photographer and his ability to engage with his subject. Can you talk about that a little bit?

Sachs: I just got my picture taken. I was on the street, and I kept thinking if the photographer was wondering if he connected with me.

For me, the window that Peter’s narrative opens into the circular thoughts of an artist is very profound because we realized that even Peter Hujar vacillated between doubt and confidence. He’s worried all the time. He is worried about the quality. He’s worried about the connection. He’s worried about the printing. He’s worried about the pose. He’s worried about the human elements. He’s worried about his signature. He’s worried, and I find that very relatable.

CULTURED: There’s something quintessentially New York about it too, just sitting with your friend and talking about the minutiae of the art, the social scene, the dynamics between people that you see every day.

Sachs: It’s quintessentially New York in 1974, pre-global economy, pre-global art market. There was a way in which you were making work for and about the people down the street, and I think that is really grounding as an artist. Instead of trying to figure out what you have that can be translatable in an international market, you’re figuring out what you have that is really intimate to the community that you live in.

CULTURED: You’ve made films set in this milieu in the past. What’s so enticing to you about that era?

Sachs: It was a very gay world. It was a very open world. It was also one in which artists were not expecting the rewards of fame outside their own parameters. I feel that work was really risky. It wasn’t looking to be liked. There was a kind of punk aesthetic to the goals and the means of creativity that I find endlessly inspiring.

CULTURED: Do you relate to that?

Sachs: Any film I make is a risk. [For] this film, I had a particular type of freedom because I sold the film to the financiers as an art project, not as a feature film. Whatever I made was acceptable to them. So that felt really rare, really independent.

CULTURED: Will you try to finance another project in this style?

Sachs: I really liked doing it. I’m always financed with the understanding that value in my work might be other than economic: artistic, cultural, aesthetic, political, homosexual. I’m always trying to question the value of my work in order to encourage people to participate. But I liked the scale of this project—it felt very intimate and personal.

But I also benefited from the collaboration with both Ben [Whishaw] and Rebecca [Hall], who were willing to try anything. They were experimental in their thought and practice. Experimentation is very hard to come upon, particularly in narrative feature work.

CULTURED: Were you experimenting a lot on set?

Sachs: I was. I think the experimentation came before when I figured out the conceptual approach to the film, which had to do with both a reality and a lack of reality. Ben and Rebecca, without asking why, would pose in a studio at one point or stand next to a window at 6 p.m. and say four lines of dialogue. They allowed me to use them and their talent as a form of sculpture.

CULTURED: Can you say more about that?

Sachs: I just think none of us knew what the film was, but somehow, and for whatever reason, they really trusted me. So I felt really open to take as many risks as I might. That is not usually how you go into narrative cinema.

CULTURED: You’ve said you’re interested in capturing intimacy in all its forms, whether it’s in the bedroom or at a dinner party. Intimacy is something that’s earned and accumulated, and, once it exists, it might not even be legible to an outsider. How do you register intimacy on screen?

Sachs: Once I was making a film in Memphis, where I grew up, and I went to Hi Records, which is where Al Green recorded all his music. Willie Mitchell, who was the producer of Al Green, showed me the microphone where Al Green sang. All his songs were [on] one microphone. The idea that there was a day Al Green sang “Love and Happiness” into this particular mic where it was recorded and that we’re still listening to that afternoon is, to me, very intimate.

The fact that whatever you’re recording will be gone as soon as you breathe—that’s intimate. I think that’s why I don’t rehearse with my actors, because I don’t want things to be repeatable. I want to capture the things that are truly temporary.

CULTURED: But then you also destabilize the viewer with these Brechtian flourishes. We get very close and then sometimes you pull us away.

Sachs: I wanted to have fun with the movie. Ben and Rebecca are both British actors working in American accents, something that I’ve never done before, so immediately I was already working in something which was a replica of reality, not reality itself.

It actually made me think a lot about the difference between European and American cinema. This felt like a very American film. When I was shooting, I thought a lot about Elizabeth Taylor, who is, to me, the quintessential American actress in the sense that, in a Brechtian fashion, she is never anything but a movie star, right? I think there’s a way in which she uses language—I specifically think of the adaptation by Joseph Mankiewicz of Suddenly Last Summer by Tennessee Williams. It is a high point of American theatrical cinema. There’s a moment when Elizabeth Taylor is sitting, giving this monologue about what happened last summer. It is so extraordinarily precise and authentic, but never real. That inspired how I wanted to make this film. I wanted it to be authentic but not real.

CULTURED: That’s interesting to say considering it’s coming from a transcript of a conversation. It’s not Tennessee Williams.

Sachs: That’s really where the authenticity comes from. That’s where the detail comes from. That’s where the beauty comes from. The film is a kind of sculpture built on that text.

CULTURED: I’m curious about the film as a response to an unfinished project. In one sense, there’s openness and possibility in something unfinished, but there’s also frustration or grief. Many people view a life lost to AIDS as a life unfinished. Do you see your film as completing Linda’s project or a response to it?

Sachs: I feel very far away from Peter [who died from complications of AIDS in 1987, at age 53]. Gary Schneider—who’s the printer of Hujar’s work and was close to Peter and was a model in many of the photographs—said, “Now you’re part of the family.” And I said, “No, I’m not.” I know more biographical details than most, but I never was in his presence. For me, it was an attempt to understand another artist’s life as a way of understanding my own.

CULTURED: Did you come across any similarities?

Sachs: The constant amount of doubt and worry. Really. I think Linda’s book is a really rare work of art. There’s a lot of artwork and films about process, but rarely do you get into the head of someone who is trying and failing and trying again to make something they hope will be good. I feel comforted by it. Also Peter is an extraordinary narrator. The detail that he’s able to provide is magnificent. You asked me what I did yesterday, I can’t remember. I don’t have that sense of recall and detail retention.

CULTURED: Are you a ritualistic person or more intuitive?

Sachs: I’m certainly process-oriented. I’ve realized that, nine times out of 10, my films are about the creation of artistic work. It’s the narrative that I know most fully. I finished shooting a film a week ago, and now I’m in the stage of unknown. That’s a stage: what did I make?

It’s a movie called The Man I Love set in the East Village in the late 1980s. It’s about an artist living with AIDS and taking on one last great project. Really it’s about how much beauty you can pack into a life while you still can.

in your life?

in your life?