“A hoarder’s paradise,” is how author Stefan Fatsis describes the 1940s headquarters of Merriam-Webster Inc.. Still standing and operating in Springfield, Massachusetts, the two-story brick building holds the country’s most complete record of American English’s evolution—down the street from a strip club and fire department. It’s here that Fatsis spent three years of his life learning what makes lexicographers tick.

After writing an article on Merriam-Webster’s dictionaries in 2015, Fatsis asked then-publisher John Morse if he could stay on as a kind of unofficial lexicographer-in-training, the staff whose job it is to find new words and redefine old ones, to observe and report how we speak and write. That experience was compiled into Unabridged, released earlier this month with Grove Atlantic. Between a robust history lesson on American dictionaries and exploration of how the Internet and A.I. have changed the field, Fatsis brings his setting and coworkers to life on the page—Associate Editor Emily Brewster, he notes, “had excellent posture.”

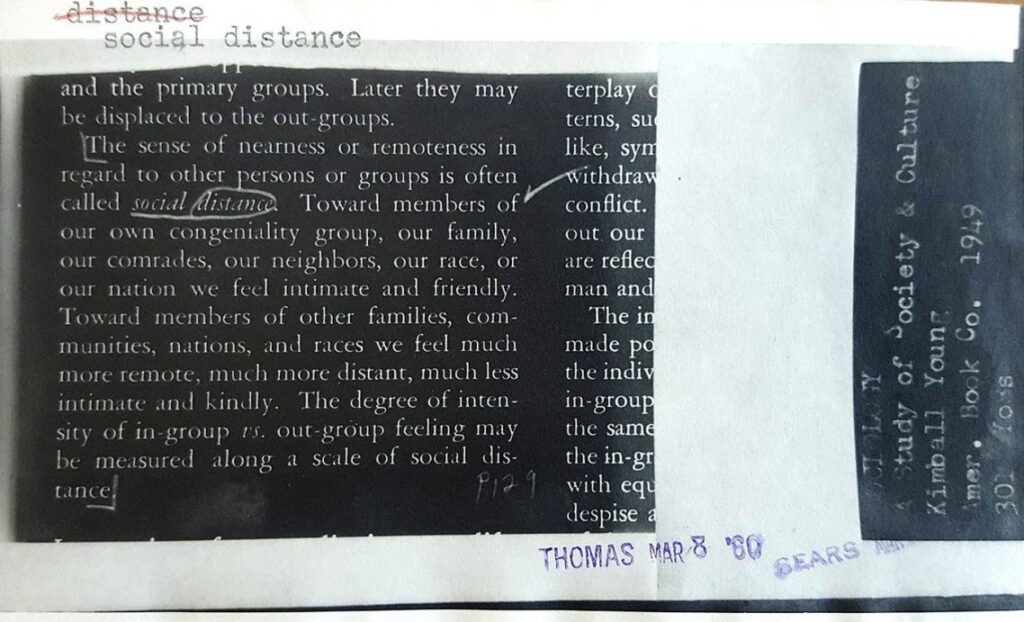

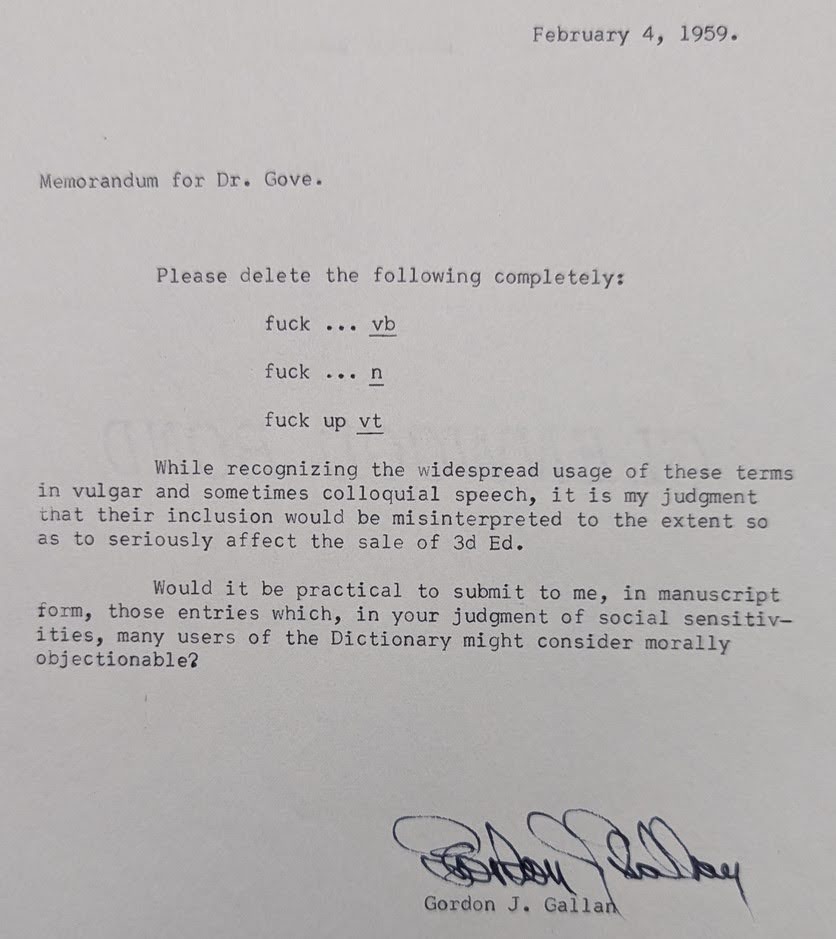

And life at Merriam-Webster is much what one would expect. There are endless filing cabinets where “slips”—pieces of paper with citations for new words and furiously written annotations—hang out, and a mostly studious group of individuals who spend the day with their noses down in a book, arguing about whether or not “fuck” belongs in the dictionary.

Unfortunately, the digital age doesn’t stop at anyone’s door: Fatsis also describes layoffs, online traffic quotas, and the looming threat of A.I. replacement. More than a close look at one American company’s bottom line, Unabridged reveals how we’ve grappled with a shared language, with the public good versus profit, and, above all else, the personal fascinations that make us who we are. Ahead of the book’s release, Fatsis sat down with CULTURED to offer an exclusive look inside the office where he battled to get one of his own definitions in the annals of American English.

CULTURED: Tell me about the Merriam-Webster offices. You mentioned in the book there’s no sprinkler system. It’s funny how so much of our history, or important documents, are just sitting in a building somewhere in a file cabinet.

Stefan Fatsis: Merriam is so analog in its appearance, and there is not only a charm to that, but a historical imperative to the collection that Merriam has. It would be a crime to lose this material. Those slips of paper and the consolidated files haven’t been digitized because Merriam and its parent company, Encyclopedia Britannica, haven’t found the money to do it. Merriam’s archive is, to me, a living embodiment of the history of American language, going back to 1900. Most of the lexicographic records for the creation of earlier dictionaries … were lost to time. It may seem sort of abstract in an Internet age, when you can look up and find examples of usage for anything in a split second. But every slip of paper is a clue to the way people thought about language and the way people lived in a particular time. I loved rummaging through those drawers.

CULTURED: What was the staff’s reaction to having you there?

Fatsis: Mostly incredibly welcoming. There were certainly staffers who didn’t care that I was there, and just kept their heads down. That’s partly because the work of the lexicographer is monastic. I’ve never been in an office where the work ethics were so intensely and rigorously abiding. One of the operating principles from Merriam-Webster, edited by Philip Gove [who worked at the company from 1946-67], was the rule that there should be no talking on the editorial floor. There were no phones on people’s desks. There was a little phone booth on the editorial floor, and if you needed to make an outside call, you’d go into the booth and use a corded phone and on a little ledger, write down the time and date of the call you were making.

That ethos of library quiet still existed when I was there. Editors would whisper, or communicate the way Gove mandated, which was on these little slips of paper. If I wanted to ask you for lunch, I would literally write, “Lunch at one?” and put it in your box. You would get it out of your box, and write, “Sounds good. See you in front of the building at one,” and put it back in my box.

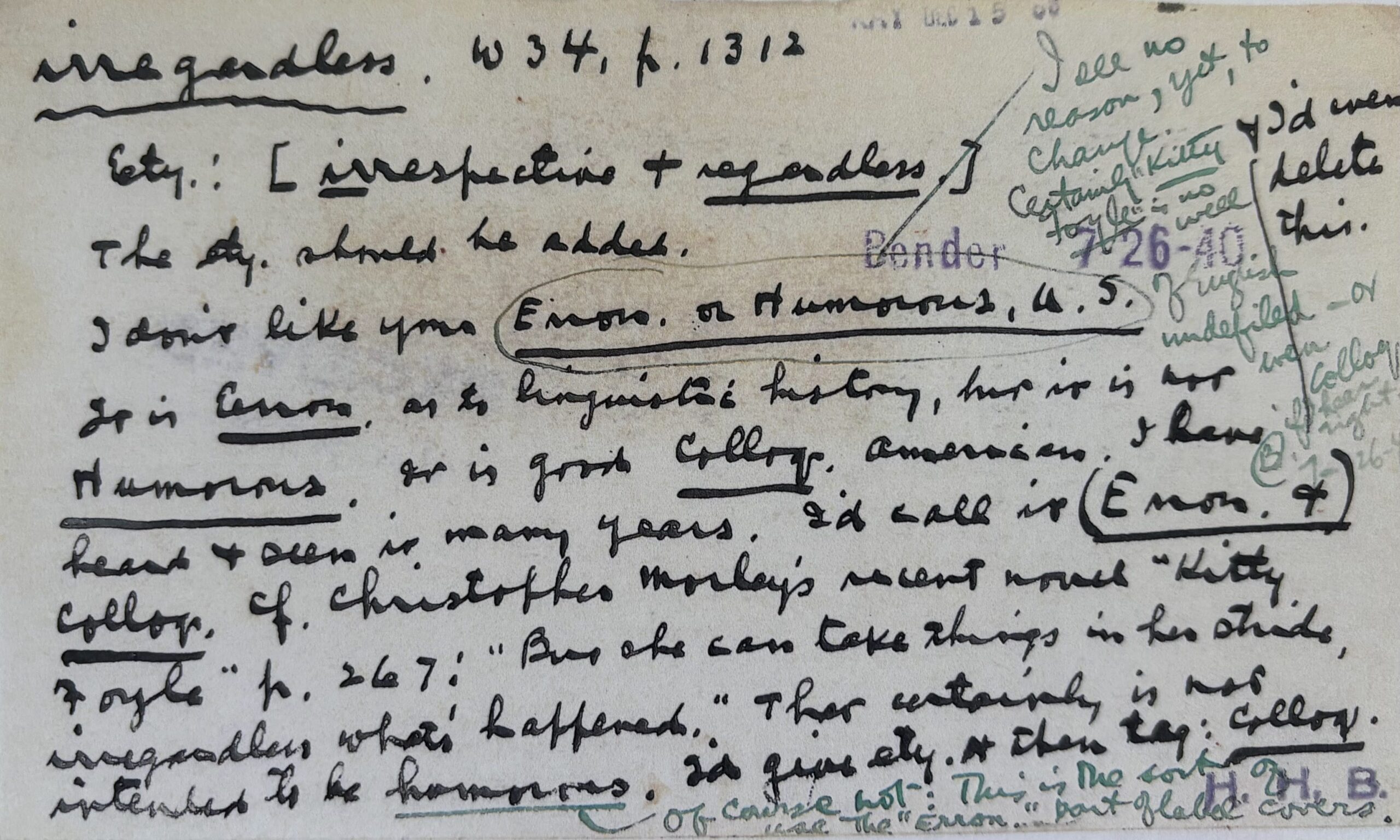

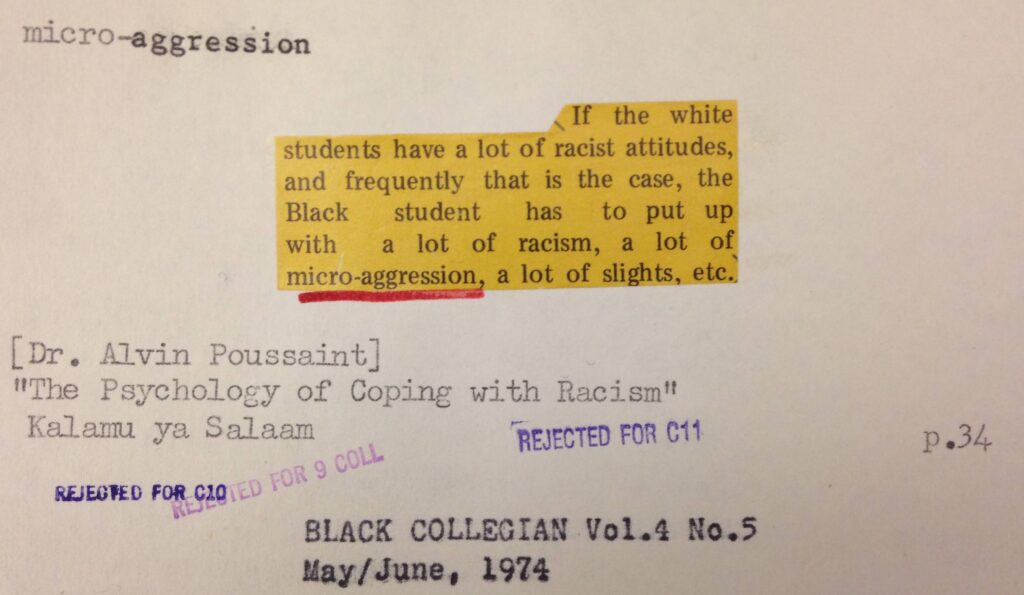

CULTURED: You do get these wonderful conversations people are having decades ago on the slips of paper that were saved.

Fatsis: Discovering that was thrilling because I felt like I was eavesdropping on important linguistic and cultural conversations that editors were having at the moment, and they were also having them over the course of decades, because words fermented in the consolidated files. One example I use in the book is the conversation over how to label “irregardless” in the dictionary. I’d read a slip and then flip it over and there would be a reply 20 years later.

CULTURED: What did it feel like when you finally got a word into the dictionary? You managed to publish “alt-right,” among others.

Fatsis: On my first day at Merriam’s, cosplaying as a lexicographer, I met the Director of Defining, which is still my favorite title ever, Steve Perrault. He asked what I wanted to do [for the book], and I said, “I want to write definitions.” He said, “Definitions that get in the dictionary?” and I said, “Yeah!” And he said, “Well, we’ll see about that.”

I wanted to test the boundaries of the modern dictionary because one argument is that the whole thing is online, why not just enter anything and everything? If somebody defines it, why not just stick it in there? The business of Merriam-Webster is getting people to go to the dictionary and type a word into a search bar and get a result. And if they weren’t getting a result, those are clicks, those are eyeballs, that you’re not getting, and that means less traffic, and that means less time spent on the website, which is bad for business. That’s a central issue to the business of the dictionary today.

As an ego-driven journalist, I wanted to see if I could get my work in there. When I finally did get my work in there, oh my God, I was so psyched. It was genuinely exciting—not because my work doesn’t get published, but because I had done something that I wasn’t sure I was even capable of doing. It was kind of daunting. I’ve written books. I was a journalist for 20-plus years. But this was more challenging, and I found it to be the hardest kind of writing I ever had to do.

CULTURED: Did this whole experience change your thinking about the dictionary? When I was reading it, I was going back and forth on the argument of: do you put all the words in the dictionary, or is the dictionary a sacred keeper of the official English language?

Fatsis: I did grow up with this idea that it’s an authoritative source. It is to be trusted. It is what defines us as speakers of English in America. If you’re growing up today, you may never use—let alone own—a book. You may never even go to Merriam-Webster. You’re probably not subscribing to the Oxford English Dictionary. If you’re confused about a word, you’re typing it into a search bar on Google and reading the first thing that pops up. More and more, that’s A.I.-generated—and in some cases, stolen from commercial dictionaries.

I appreciated Merriam’s desire to maintain standards and to stick by the tradition of ensuring that a word has penetrated culture enough that it merits being added to the book. It’s a tricky balancing act because commercial dictionary publishing is unbelievably challenging. Merriam-Webster, and to a lesser extent dictionary.com, are the only remaining dictionary companies in the United States that have full-time staffs. Merriam, for now, is making it work.

CULTURED: They had that great social media moment recently about A.I. where they were like, “We created a new large language model,” and it was their newest dictionary.

Fatsis: That was great.

CULTURED: Even my friends were like, “Did you see Merriam-Webster post about A.I.?” It’s changing so rapidly.

Fatsis: I was super cognizant of the fact that anything I was typing was, in all likelihood, going to be outdated by the time the book got into stores. I was trying to be as careful as possible. Because the reality is, you can produce a dictionary using A.I. People have done that already. Not a commercial dictionary, but a dictionary.

A.I. is a moving target. And to go back to Merriam’s decision to publish a new, physical book—I mean, it’s a great troll, right? That social media post and video were brilliant, positioning the book as the ultimate in authority. The tagline on Merriam’s video is: “There’s artificial intelligence, and there’s actual intelligence.” When I was there, there was no expectation that the Collegiate Dictionary from 2003 or the Unabridged Dictionary from 1961 would ever appear in print again. It was completely a foregone conclusion that we were in the digital age forever and we were done with books.

Merriam’s decision to produce this book—a real revision that editors spent two years working on—was sort of hush-hush. It didn’t leak. Nobody in the lexicography subculture knew about it. So it raises the question: why do this? This book says, “You can trust this book, and you can’t trust the other stuff.” The irony is that Merriam uses A.I., of course, like every other digital media company. There’s a chatbot on the homepage. They’re threading a really interesting needle.

CULTURED: Do you feel optimistic about the future of the dictionary at this moment?

Fatsis: Honestly, it’s hard to be optimistic. We live in, at least for now, terribly anti-intellectual times. The prospect for the business of the dictionary isn’t great because of A.I., because of Google’s dominance, because of the need to game SEO [search-engine optimization] and have that be a central core of your business. The number of full-time lexicographers in the United States 20 years ago was around 200, and today, conservatively, it’s less than 50, maybe even 30. Those are not good signs.

The craft of lexicography, though, is so important to who we are as humans, as Americans, that—like journalism, which has increasingly turned to a nonprofit model—I’m hopeful that similar creative solutions are going to emerge. The question is, what’s the model? American dictionary publishing has been a competitive commercial enterprise pretty much since George and Charles Merriam acquired the dictionary in 1843. The Oxford English Dictionary is a different model—it’s supported by the university. The OED brags on its website that it’s never made money. So is there some public-private model? Some benevolent, rational billionaire who will rescue the dictionary and make sure this work goes on into the future? I hope so.

CULTURED: It feels similar to journalism, in that these things once considered public goods were also profitable, and now they’re not. Do you feel, similar to journalists, that lexicographers are a little nihilistic in the office? Or, are they maintaining more enthusiasm than journalists are?

Fatsis: What I found is that lexicographers who are lucky enough to still have jobs are grateful for those jobs. They really like their work and believe that it’s important, interesting, vital work. John Morse, the publisher of Merriam-Webster, once said to me that they’re in the business of creating knowledge. I think everyone still able to craft definitions that other people rely on believes it’s a public necessity. I didn’t get the same sort of jadedness you get in a newsroom. Instead, there was more weariness, fear, and concern about what’s happening. At the same time, there’s this belief that the work really matters, and that the people fortunate enough to still be doing it appreciate that every day.

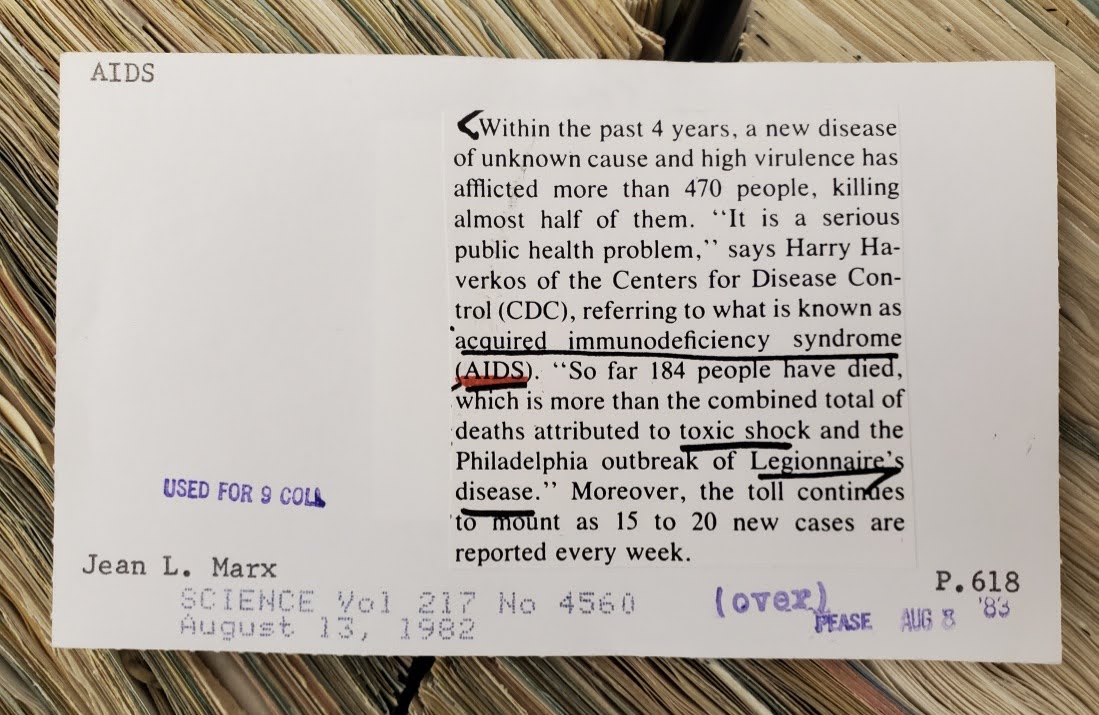

When the pandemic hit, Merriam acted like a newsroom. In the old print days, the fastest a word had ever gotten into the dictionary was “AIDS”—it took two years from the first appearance of the acronym to its publication in Merriam’s Collegiate Dictionary. When the pandemic hit, there was this urgency in the editorial operation at Merriam: We have to do something now. They broke the mold and entered “Covid” and related words 34 days after the World Health Organization created the term.

That was remarkable, but it also reflected this core belief that defining words isn’t just historically important, but that there can be urgency to the work. This was a job that for generations had the longest timelines between doing the work and seeing it published. That’s all changed because of the Internet.

And the Covid example, to me, demonstrates how important language remains—and always will be. Covid words were a matter of life and death, and the dictionary rose to the occasion. It gave people the information they needed in a time of crisis. Lexicographers understand that what they do matters. They want it to still matter.

in your life?

in your life?