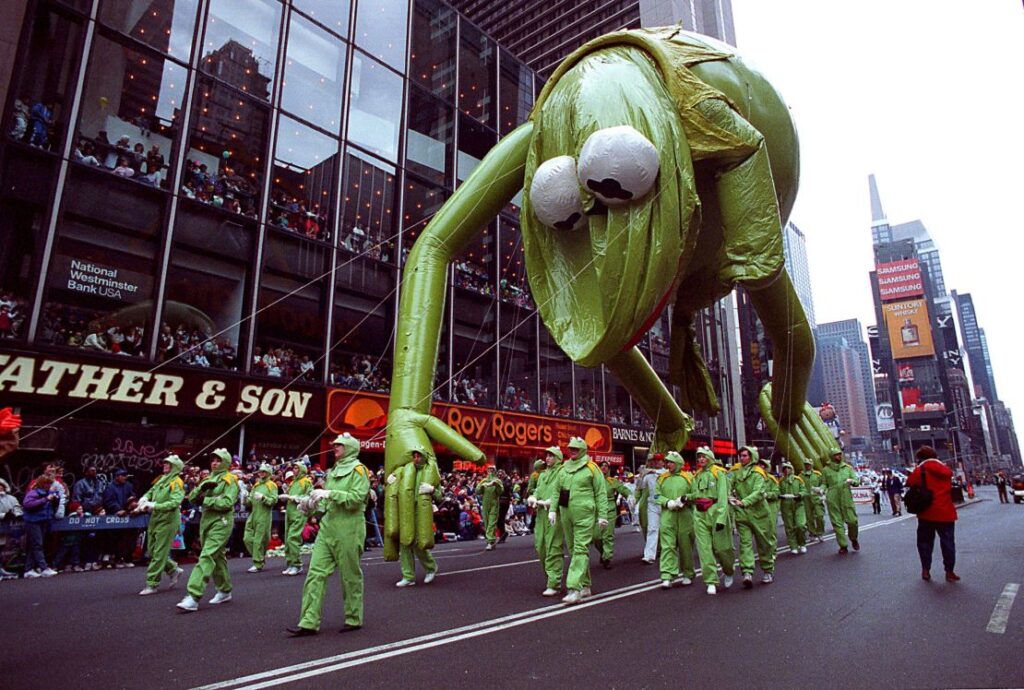

Jim Henson made his last televised appearance with Kermit the Frog, the instantly recognizable Muppet he created in 1955, on May 4, 1990. The puppeteer would die of toxic shock syndrome (due to the complications of a bacterial infection) at the age of 53 12 days later. Six months after his memorial took over, Muppets and all, New York’s St. John the Divine cathedral, Kermit would make his own processional tribute to Henson in his grand comeback to the 1990 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. However, it was the amphibian’s appearance in the holiday tradition a year later that really made headlines. Accounts vary, but either a lamppost or a tree impaled the Kermit float, leaving its usually perky head deflated for the rest of the journey. There were other injured parties that year, Betty Boop and the Quik Bunny among them, but none left quite the impact as the crestfallen Kermit—an efficient public service announcement that life, even for a cartoon character, isn’t always sunshine and rainbows.

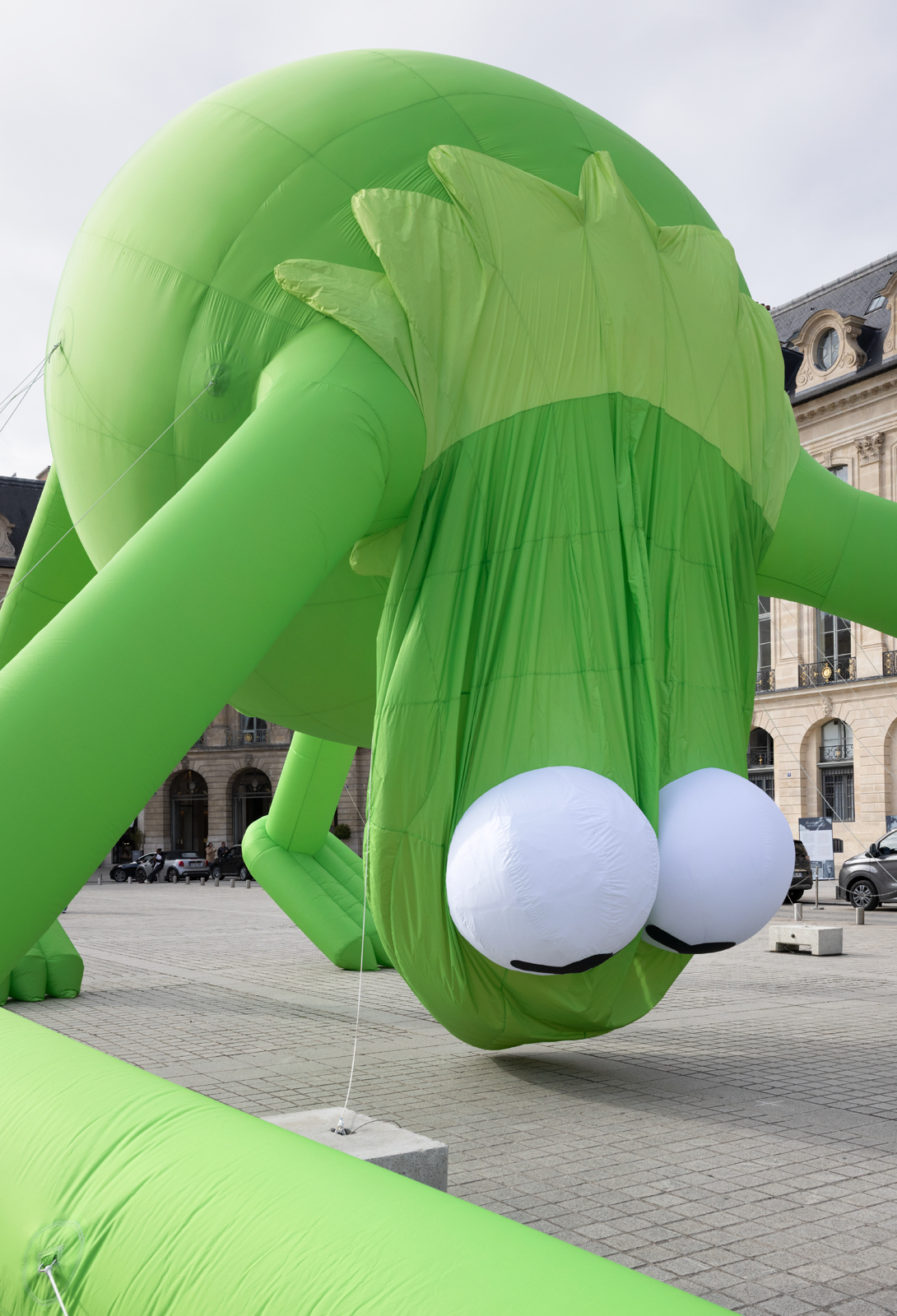

Alex Da Corte was 11 at the time. He doesn’t recall watching that specific Thanksgiving parade, but came upon the Kermit incident years later through photographs. It inspired the Venezuelan-American artist—who has often mined the topography of made-for-kids media, from Mr. Rogers to Sesame Street, over the years—to immortalize the totemic frog in his depressed state with a massive inflatable sculpture. Debuted in Buenos Aires in 2018, the artistic intervention was resurrected this past week for Art Basel Paris (on view through Oct. 26). The setting for Kermit’s prostration? The Place Vendôme, where Paul McCarthy’s anal plug lookalike Tree had been the victim of a vandalistic deflation in 2014. Kermit’s presence has certainly been more family-friendly, but its reverberations are no less unsettling. I met Da Corte a few miles away at the Musée Picasso to unpack the piece’s life cycle, his relationship to failure, and why he’s sticking with the parade charade for his new show with Matthew Marks opening in New York next month.

CULTURED: This week marks the first time that you activated Kermit the Frog, Even as a performer. How did it feel to be in it and not just orchestrating it?

Alex Da Corte: The wind and the rain played a huge part in how it feels because this Kermit the Frog is literally depressed, yet there’s these six performers trying to keep it aloft. And as you lift its limbs off the ground, the wind will catch it and just move everybody. There’s no way to plan for it; when we were walking over to the performance, there was a light drizzle, then the sky just opened and fell. What was wonderful about it was that after so much heavy rain and a very sad Kermit, the sun came out and there was a giant rainbow. It was incredible because of course there’s Kermit’s relationship to the song “Rainbow Connection.”

CULTURED: And you premiered it in 2018…

Da Corte: Yes, for “Hopscotch (Rayuela)” the Art Basel Cities exhibition Cecilia Alemani curated in Buenos Aires. She had curated a project with me in 2016 for Frieze New York, where I did a huge float that was a replica of this work from the original Batman that Tim Burton did in 1989. It was this big crying baby. I like the idea of essentially remaking, over time, a series of floats that then [could become] its own kind of parade. I like [thinking of] them co-mingling and not just being these one-off things.

CULTURED: And were you watching the 1991 Thanksgiving Day parade where the actual Kermit deflation incident occurred?

Da Corte: I only know it through pictures. The thing I’m so very interested in [with] that particular event was incidentally related to the photo documentation of the work, which has the Kermit float, as we know it to be, with its head sagging and these 25 performers underneath of it, but it’s in front of a store on Fifth Avenue called Father and Son. The father and son-ness of it all was the thing that really spoke to me because Kermit the Frog is an invention of Jim Henson, voiced by Jim Henson. It is not Jim Henson’s child, but it is in some way…

CULTURED: His progeny.

Da Corte: Yes. I’m quite interested in the invisible labor that was Jim Henson’s life’s work, and [how he was] behind the scenes. He could walk down the street and not be known, but like Kermit the Frog, the puppet, could not be on the road without being a celebrity. This [photo in front of] “Father and Son” just made me think more about the relationship to the things we put into the world, into ourselves, and what family looks like. How does one meet the expectation of another in any relationship? Is there a baked-in failure factor in all of us? That even this bright and buoyant parade float, which is a symbol of this beloved, hapless romantic swamp frog, then also fails, that too is quite human. I thought all of that was so relatable. I was interested in seeing any kind of big monument in some sort of collapse.

CULTURED: There’s also this whole idea of what makes something actually family friendly. I can only imagine the kids who saw the deflation of the Kermit during the parade.

Da Corte: On screen, in the cartoon world, behind the screen, things are free of any kind of relationship to gravity or humanity or the real pains of one’s psyche. But when you make a big volumetric sculpture of a cartoon, then you have to deal with shipping, crating, inflation, deflation, tears… real things. It becomes more related to our bodies than ever before off screen. You take a [person dressed as a] mascot of a cartoon character into the streets, and they start waving and making people happy. But then they get hot. They need smoke breaks. You, all of a sudden, engage these symbols with things that they typically are not associated with—even though they are a beacon for people just to get by, because we find safety in the screen.

CULTURED: The Place Vendôme as a setting is also both iconic and loaded, with the vestiges of empire and the column, the jewelry stores around it, and the history of artworks installed by the likes of Paul McCarthy, Yayoi Kusama, Elmgreen and Dragset. Then you bring a frog into it. Did you think about the fact that you’re showing a frog in France and whether that was comical to you?

Da Corte: It is comical. What was striking to me about seeing the float in the place on Sunday was how funny it was. I always knew it to be kind of sad, but I don’t know if I also knew that it would bring me a lot of joy just seeing the pathos in it. In a way that’s like slipping on a banana peel or something. It points back to [Gustave] Courbet knocking down the [Vendôme] column, and it engaged with it in a way that I was thinking of conceptually, but then physically seeing it, seeing the rain, seeing the kind of Buster Keaton-like struggle to hold this thing up and that it is just a charade… The performers are instructed to just wave at people and keep smiling, even though they’re really in labor and wet… There’s something about it that relates to the face of politics today and the face of the world, which is just like, “Keep calm and carry on.” There’s holes in those systems and we know it.

CULTURED: That feels very real with the musical chairs of ministers and the general state of the French political system. And then the Louvre heist which happened a few steps away from the Place Vendôme…

Da Corte: Think of The Great Muppet Caper, where they also tried to steal some large jewels. This just situates our realities into an absurdist theater.

CULTURED: How has your relationship to failure evolved over the course of your career?

Da Corte: I’ve always been interested in failure. From a very early age I was so in love with this one movie called It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World which involves this person, played by Jimmy Durante, kicking the bucket on the side of the road. He’s buried a pile of money under a big W [in Santa Rosita State Park] so all of these people who are driving down the side of the highway in California, who witness this crash and hear his last words, then team up to go find this money. It becomes a crazy hijinks with people crashing planes and cars to find this money. And in the end, there is money, and everybody gets hurt in the process and ends up in a hospital. This bawdy actress named Ethel Merman, who’s a famous loud mouth and singer, storms into this hospital with all these goofy men who are now all broken after trying to find the money. She’s going in to have the last word and tell them that they’re just stupid men, and she slips on a banana peel. And I love that. There’s something about the banana peel: It’s so ham-fisted but it’s so relatable. Even at your best your fucking heel breaks. Like my mother used to say, “You just can’t get in from out of the rain.” Not to say that I’m a pessimist because I feel like I’m quite the optimist—but I recognize that rainy days happen and that’s also okay.

CULTURED: What is making you optimistic right now?

Da Corte: A friend asked me, “What are you going to do for the day?” And I was like, “I have to go dress up like a frog and be in a charade parade.” And they were like, “That’s a beautiful life.” It gives me some optimism that I can, for a moment, make some people happy.

CULTURED: There’s also something so beautiful about collective comic relief, because so often now our comic relief is very individualized and algorithmic, with memes and inside jokes. Versus being confronted with one thing in public and having a reaction to it, even if you didn’t know what it was before seeing it.

Da Corte: I think people are looking for any kind of space to break out of what seems to be our lives, overlooked by these kinds of algorithmic systems. To just break from that is exciting. It doesn’t come automatically and I work for that. Maybe the thing that gives me some kind of joy is finding those moments where I can break out of that set system.

CULTURED: What are you excited about in terms of things you’re working on?

Da Corte: I’m working on a show that opens at Matthew Marks Gallery on Nov. 7. It’s the first time I’ve done a show in Chelsea. It’ll be in two of his galleries and it’s a bunch of new sculptures that I’m very much excited about.

CULTURED: Any hints about what we can expect?

Da Corte: One thing which is very dear to me is this replica of a Paul Thek work I have wanted to make for almost over 20 years. He made this work in 1967 called The Tomb; it was famously shown in New York at the Stable Gallery. It traveled all around to lots of different museum shows, [including] in 1981 in Rotterdam, where upon its completion, the work was sent back to him, [in such a damaged state that he refused to accept it at customs], and it was thrown away. So it’s been lost since 1981. I’ve painstakingly replicated it based on just the few photographs that exist of it. So it’s been a very curious work about photography—similarly to what we were speaking about in relation to the Kermit the Frog parade float and the “Father and Son” moment—really considering physicality through photography, which we do so much now.

Paul made all these works that he called Processions, and the show is called “Parade.” So it’s also so harmonious to me to be in a charade parade and then to be doing this show with this parade of sculptures, including this Paul Thek work. And I’ve been thinking about Rimbaud’s Illuminations, and there’s this part where he’s witnessing this savage parade, and he’s within the savage parade, and he’s seeing the savage parade sort of pass him by. And I liken that idea to at any many moment that we have in our life, be it our whole life stretched out or just something that happens in a second in a day, where you see something and you’re sort of on the side witnessing the parade, you’re inside of the parade as a participant, and then the parade eventually ends, and you remember the parade. It passes you by. Be it savage or joyous, to recognize what part of the parade you’re in at any given moment, I think is a place to find optimism and to kind of keep taking steps forward.

in your life?

in your life?