I did not grow up a Belieber. I did believe, of course, in a menagerie of false gods that would ultimately betray me: boys—and worse, girls—repetition, starvation, simplicity. Patricia Lockwood, the award-winning poet and writer was raised a vitriolic believer but left the Church young, finding her faith in eccentric turns of phrase and bizarre twists of fate, a cyclical, carnivalesque spirituality. Her latest “novel,” though her writing requires a more expansive term (myth? prophecy? memento or auto-anti-hagiography?), is called Will There Ever Be Another You, and is a secular mystic’s recollection of long Covid, her husband’s near-death experience, and writing as a vocation.

Lockwood first found viral fame online, posting ecstatically crass Internet witticisms. Her regular criticism in the London Review of Books is as well-known for its spikes of epiphanic grace as it is for its one-liners dusted with Internet residue: she once, for example, referred to Karl Ove Knausgaard as “a yassified Noah.” “’I am obsessed with Madonna,’ her character admits at one point in the new novel, only to correct herself: ‘No, I am obsessed with the Madonna.’” Lockwood’s protagonist asks her mother where she was conceived, and learns that her parents made love in a mudhole after her father returned from a trip to the Holy Land. It’s no surprise that she treats the subject of virus-induced brain fog as an opportunity to pen a “masterpiece about being confused,” an experiment in biography under life-altering conditions, rather than the typical linear illness narrative.

“Biography is gossip,” Lockwood writes. I mentioned earlier that I wasn’t a Belieber: I actually converted this summer, when Justin Bieber released SWAG II, which I listened to fervently while reading Lockwood’s book. It sounded like a rebuttal of the gossip, a love letter to the media-maligned woman who looked after him during his afflictions with oft-doubted chronic illnesses. In both the album and the book, sirens blare, flares rise, and patient zero is a flirt and a comic—an avenging prophet. Lockwood, for her part, circles the canon of Sick Woman Books, but she refuses to fall onto the fainting couch. Instead, she takes psychedelics, reclines, and writes her hallucinations in a secret notebook—until her husband falls ill too, and she’s thrust out of the sickbed and into a nurse’s uniform. He has visions that are difficult to believe, inhabiting the role of hysterical woman as his wife sews up his wound in a purposeful reversal of the insane, ill wife trope.

Will There Ever Be Another You seems set in a billowing circus tent of the mind, where Lockwood performs linguistic trapeze acts and traverses the gender binary like it’s a tightrope. “Top down babe, let the roof go missin’” Bieber sings on “Love Song.” Lockwood wrote this book from inside the attic of her mind—“I would say that this is an attic book,” she told me, “As the roof is being lifted off.”

If the connection still isn’t clocking for you, consider this: A beautiful woman I know texted me that she found God through SWAG II. If you’re still thinking WHAT? then I’m still on the right track: In Lockwood’s surrealist exploration of “the integrity of incoherence,” she calls that word “the greatest … in the English language.” Earlier this month, Lockwood and I met over the phone to talk chaos, illness, Jesus, genre and gender bending, and the Internet.

I want to start with a trigger warning: I am quoting you a lot today. Is that annoying?

If it’s annoying, I’ll be like, “That’s annoying.”

Perfect. I’m really annoying, so it’s helpful when a woman I respect tells me it’s getting out of hand.

I can’t wait.

You wanted to write a “masterpiece about being confused.” Illness scrambles chronology, narrative, and our notions of selfhood—and yet illness chronicles usually attempt to reassemble the timeline, or restack the Jenga blocks, if you will. Instead, you painted a surrealist portrait of the Jenga blocks on the floor. How did you find your form?

Nobody has really asked about this yet, which I find interesting, but some people have said, “These are the quotes that are sticking in my brain.” Weirdly, the ones that keep coming up are the ones that I kept taking out and putting back in because I wondered, Is that too on the nose? Do you remember the beginning of the pandemic, when everyone was having these deep dreams about the past? Our brains had no new input. So we were delving back into memories and dreams, thinking of things that we hadn’t thought of in a long time. The book seemed to be taking place in that dream space, processing what was currently happening by going back into the past.

You wonder at one point, “What if there were a person whose mind had no reception rooms, but who carried you immediately into the tabernacle,” which feels connected to the moment where you imagine the mind’s front porch. What room of your mind were you in while writing?

I’m usually in the attic. Being in the attic is a great feeling. You should be writing your books in the attic, unless you’re in the basement. There are basement books, there are attic books, there are kitchen books, and there are bedroom books. I’m formulating this theory in real time. My best cousin Paige–at her house, there was this crawl space that was linked to her attic, and this book felt a bit written from there. I would say that this is an attic book as the roof is being lifted off.

Is an attic with no roof kind of your church, on a vibes level? As someone who’s left the church but is deeply in touch with the spiritual, you render illness a mystical experience here.

You’re right. I thought, You’ve had a mystical experience. You need to treat it seriously. Part of that is not laughing at it. In this book, there’s humor, but you’re not laughing at the fact that this is happening to you. Funny things are happening; they’re threaded through, but you’re taking the state you’ve been swept into seriously. It was very much a mystical state.

The sick woman book is a famously maligned and misunderstood genre, so you’re definitely walking a tightrope. Were you purposefully subverting that genre or attempting to enter that canon?

I didn’t think about subverting the genre–I was thinking about the books that came before. The narrator’s in the doctor’s office trying to explain that she can’t work, and what she’s thinking about is Pale Horse, Pale Rider. I love any book where someone’s getting their temperature taken every morning and being given gruel to eat. I love all that shit. What I wanted to thumb my nose at was the way people react to those books, the way they don’t take them seriously. There is definitely a thing people do: “I need to put on my big doctor voice to describe my illness so that people believe that it happened to me.” I thought this was too weird for that. I was seeing gorillas in the trees. Let’s talk about [the experience] like it actually was. Let’s give it that respect.

Your husband’s illness is portrayed as a much more scientific story, and one that allows you to play the caretaking woman and the sick woman—two feminized archetypes that are not usually embodied simultaneously in literature, though they so often are in life.

All of that was very fun for me—not in life—but to play with. I was thinking about how illness makes things happen in novels. Take Pride and Prejudice. It’s like, you’re gonna have a carriage ride to the big house in the rain, and you’re gonna get a little bit damp. You’re gonna get sick! You’re gonna have to stay there, and someone’s gonna have to fall in love with you. This is how we made things happen historically in novels, when we knew much less about disease models. Let me just bring in my own conspiracy theory here: get your feet wet, you will get a cold.

For sure. I have female hysteria from playing in the rain once when I was seven.

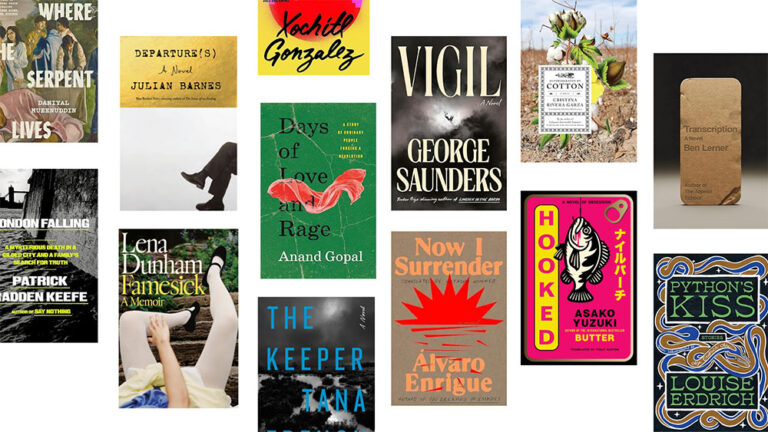

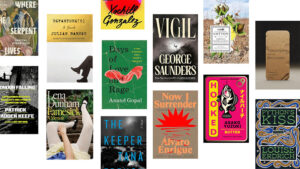

My character is floating along in this deranged cloud, but she is still able to do things. When I was in that state, I still had to do my job, which is to write about books. I was wading through syrup, I had sandbags tied to my arms and legs, and I’m really proud of the way some of those pieces came out. I was able to get up in the morning and read the latest George Saunders and make my little comments and then go into the front room and attend to a spurting, gaping wound that didn’t stop bleeding for 100 days.

You’re really greasing that priest daughter to girlboss pipeline.

I was like, Guess what, bitch? I can do this.

Illness makes things happen in this novel, but it also prevents them from happening. You write that you’re having a “Protagonist Problem. I could not move, or make anything happen.” This book sometimes reads like a memoir, like in that moment, and at other times like a commonplace book or a Margery Kempe-style autobiography of spiritual agony.

I have always been a fan of books that didn’t quite fit in categories. Leonora Carrington’s Down Below is a model for this one. Yes, there was something that brought this on. World events, chaos, as in Carrington’s story of her own madness. But it’s also private and personal—she takes us into the corridors of the asylum with her. I like books that are published after people have been dead for 50 years. When someone is like, “We found this sheet of paper in their drawer, and we’re publishing it unedited.” I like to read my way through a writer completely, and I like the commonplace books, diaries, letters…

Your voice is so entrancing, it definitely gives shepherd, in that I want to follow you. Actually, my impulse to use the word “follow” there is intriguing, because you so deftly infuse Internet lingo into your voice. Where other writers might avoid online slang or pretentiously demean it, you use it to deepen your analysis and seem to see it as another gem on the kaleidoscope.

That language is in people’s minds, and it’s weird to subtract it from our writing. This was the whole idea of No One Is Talking About This. We are swimming in this for 8 hours a day, and we’re just like completely redacting it from our creative and lyrical writing? Why are we doing that?

And you illuminate the ways that, while the Internet can be isolating, experiencing it IRL with another person can be a form of communion. Sending a friend a screenshot is one of the greatest joys left to us in this dying and decadent society. You used the phrase “a private language full of pleased loan words” to describe your niece’s vocabulary, but it also felt like an apt description of the lingua francas developed in Internet communities.

Writing is an attempt to reproduce the music of the mind, and part of that music is jingles and commercials, catchphrases. I was the sort of kid who could speak in lines from TV and movies. I had a fabulous memory for those things, and that is part of what returned during my illness—these insistent catchphrases felt like they were trying to tell me something. I was much less on the Internet during that time, but it’s part of the rhythm of the mind, the way we frame things. Looking at major life events and seeing those things phrased in Internet language feels a bit diminishing, but at the same time, let people splash in the mud, man.

We have to get our feet wet so we can get the disease that sparks the plot. I was interested to read that you don’t understand fandom, which feels like a contemporary iteration of the cults of saints to me. But maybe that’s because you left the Church behind, which gives you a more anarchic orientation to figures that other people have a hierarchical reverence for?

Because of the religious upbringing, it felt very hinky to me when people go there. I don’t recognize authority, and I don’t recognize fame. If I meet someone who is in a supposed position of authority or who’s supposedly famous, I don’t feel those things that other people apparently feel, which I hope also protects me a little bit, because I also don’t feel famous myself. Fame is bad for any writer—particularly for poets.

In this book, your character goes to a conference on biography. You’ve written criticism about poetic biographies, so I’m curious about your decision not to make this book an autobiography. In your essay on Sylvia Plath, you call her diaries a “biography of aim.” Was this a biography of aimlessness?

I went to this fantastic conference on biography in Lisbon. I felt this resistance in myself so deeply, particularly when they would talk about poets, because I knew as a person who wrote both poetry and criticism that what we need to be doing in poetic biographies is talking about the process of getting ideas, and it’s impossible to talk about. My character dips into it a bit when she wonders, “Why did Emily Dickinson experience this period of enormous creative fertility between 1861–65?” It’s the war. Obviously, things are happening in private lives, but we often forget about the fact that world upheavals are felt within individuals. This book is about world upheaval through an individual. Suddenly, no one wanted to be in their own life. They didn’t want their jobs. Doctors retired. People wanted to be doing anything other than what they had previously done. I saw that everywhere I looked. My character is genuinely confused, and confusion is a thread that runs through all of my work. Why do people act this way? Why do we put faith and trust in the people that we put faith and trust in?

As you write, you’re looking for “the integrity of incoherence.” A sentiment which, no MFA, gave me a lot of permission. As someone formerly addicted to argumentation, I have been trying to write in a way that once seemed too digressive, but is actually what allows a reader to reach the epiphany they need.

I worry sometimes–I don’t really have arguments. There’s not a thrust. I look at the novel as a plane where something’s happening, people are riding horses, there are buildings, there are villages, you’re going through that on a physical plane. And then you experience this extrusion—this wide or open feeling, which is suddenly channeled into something much smaller, a much smaller tunnel or tube, in writing about it.

I have a possibly deranged final question—the husband character’s stomach wound read to me as perhaps paralleling Jesus’s famously vagina-shaped side wound, which feminist scholars have written about a lot. Were you thinking about that?

Oh, it was absolutely how both of us were thinking about it the entire time. In illness, derangement, or madness, you’re experiencing your own lack of concreteness. There was something perceptually interesting to me about shapes, plasmas, liquids, substances: the things that flow through people. It was concrete, but it was also mystical. It had such correspondence to the religious imagery you’re talking about, but also imagery of the body. Religious imagery is interesting because it is imagery of the body, and because it crosses gender lines in such a brazen way. He was saying, “I swear that I have memories from the transfusions they gave me.” I’m thinking, What on earth could that possibly be? You’re not supposed to know who donates organs, who gives you their blood, but it is documented in the scientific literature that these things crop up from time to time: you get a kidney from a pianist, and you wake up and want to play. These are things that a man was experiencing, and they are usually understood as feminized insights or feminine experiences because they are things not believed.

in your life?

in your life?