A muse to Pina Bausch, a confidante to Rick Owens, a case study for José Esteban Muñoz: Vaginal Davis is the blueprint. The category-allergic artist and musician’s taste for the stage was jumpstarted by the rendition of Mozart’s The Magic Flute she saw in South Central LA when she was only seven; she has reigned as the Queen of the Night over an abundance of scenes—drag, queercore, experimental film, and fine art among them—ever since. This fall, a survey spanning five decades of Davis’s contributions to these fields and beyond is landing at MoMA PS1 in New York. Ahead of its opening on Oct. 9, I called up the artist, who currently lives in Berlin, to talk legacy, therapy, and mortality.

Were you born a performer, or did you become one?

I’ve been performing since I was a child, and I think I turned myself into a performer because being shy and reserved just wasn’t going to fly. People think performers are extroverts, but I’m an introvert. I have to turn into this other thing to get almost anything done. If you peel back all the layers—if there is a “real me,” because after so many years you just become a construct—the real me is shy and sort of dorky.

What is the construct of Vaginal Davis?

It’s hard to articulate because there’s no clear line between the private person and the public persona. That happens with a lot of performers, writers, artists, especially people in entertainment. Everything gets blurred. That’s why I’m in therapy—once a week, sometimes twice. I’m a mess-tacle: a big mess plus a spectacle. When you’re a mess-tacle, you need someone outside your realm to bounce things off of. Reflecting on my life, I see mortality differently. I never thought I’d live to be 64, especially with the AIDS pandemic that took so many from my generation. The goddesses laid out a path for me, and you accept your lot in life and move on.

Based on the extraordinary nature and scope of this show, which spans so many mediums and so much time, what do you hope the legacy of Vaginal Davis is?

People were always accusing me of being artsy-fartsy, even as a child. I was just doing what felt organic to me, not thinking of it as a body of work. I’d do something, move on, never look back. I wasn’t a good archivist. Luckily, other people saw value in what I did because I rarely kept copies. Growing up poor, in a non-academic family—I was the only one who went to college—there wasn’t a careerist mindset. Today, most artists come from generational wealth or privilege; it’s rare for someone from my background to be recognized at all.

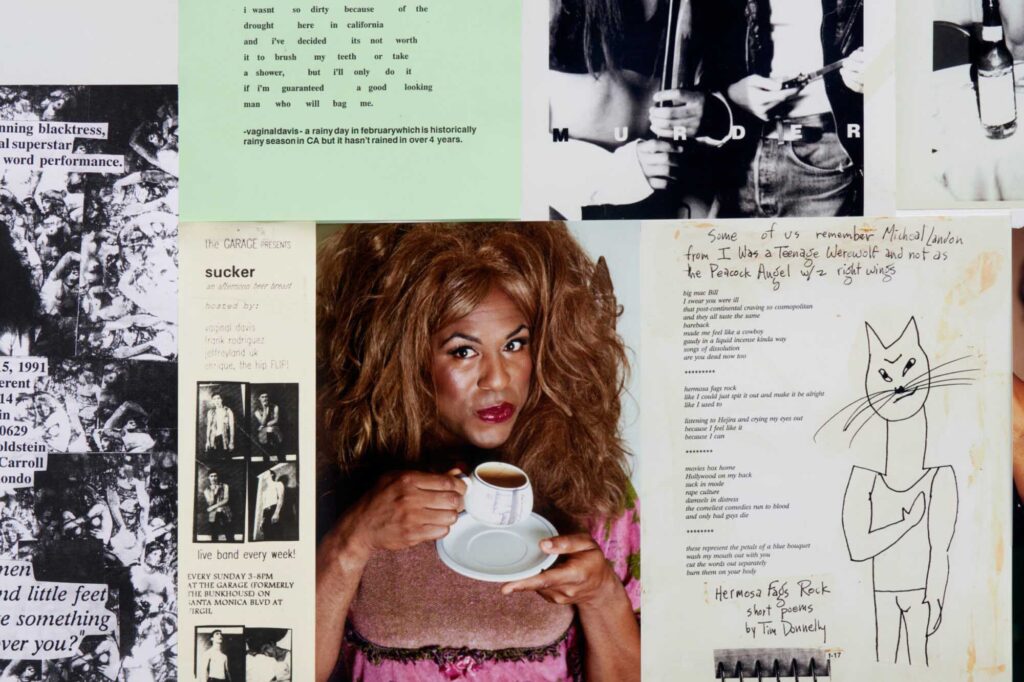

Jeff Briggs, a high school student back in the ’80s, kept a lot of things I produced that I didn’t. Through him, Moderna Museet [where the show debuted before traveling to MoMA PS1] was able to gather much of what became this exhibition. With all the moves, floods, and damaged apartments, it’s a miracle any of it survived. When Moderna first staged the show, I never thought it would travel. It was a shock to hear it would come to New York. If you’d told me this eight or nine years ago, I’d have laughed in your face. Things like this don’t happen to people like me. I guess that’s my legacy—it’s a patchwork that others saw value in, even when I didn’t.

Something I’ve heard you say many times before is, “You can’t change institutions from the inside; they always wind up changing you.” How have you approached these institutional collaborations?

I really believe that they’ll always change you. You have to make your “yes” mean yes and your “no” mean no. I follow the advice of the legendary Diana Vreeland: “There is elegance in refusal.” If something doesn’t feel right, I don’t do it.

“Vaginal Davis: Magnificent Product” is on view at MoMA PS1 in Long Island City, Queens, from Oct. 9–Mar. 2, 2026.

in your life?

in your life?