This week, Brian Droitcour helps us make sense of our moment—its mediatization, its sneaky paradigm shifts, the potentials and perils of A.I.—through the visual and performance work of tech-savvy artists and writers. His guide takes us to Brooklyn and Queens, and leaves us shrugging in the lobby of MoMA.

I had seen the word “groyper” before, but I only looked it up when it started trending, right around the time a Utah police chief stood before TV cameras and deadpanned: “notices bulge OwO what’s this?” Online life bleeds into the public sphere with absurd speed and horrific consequences. People lose jobs over posts on X, while the FBI floats the idea of labeling trans people “nihilistic violent extremists.” Media and government still pretend the world splits neatly into right and left, but social media platforms have splintered society into a matrix of smaller, shifting cells, where groups cohere around memes, fetishes, and surges of love and hate—not tidily defined ideologies. Generative A.I. companies promise to clean it up, to make everything online smooth and legible. But the chatbot user can become the smallest cell of all: a solitary paranoiac trapped in solipsistic loops, spiraling away from reality.

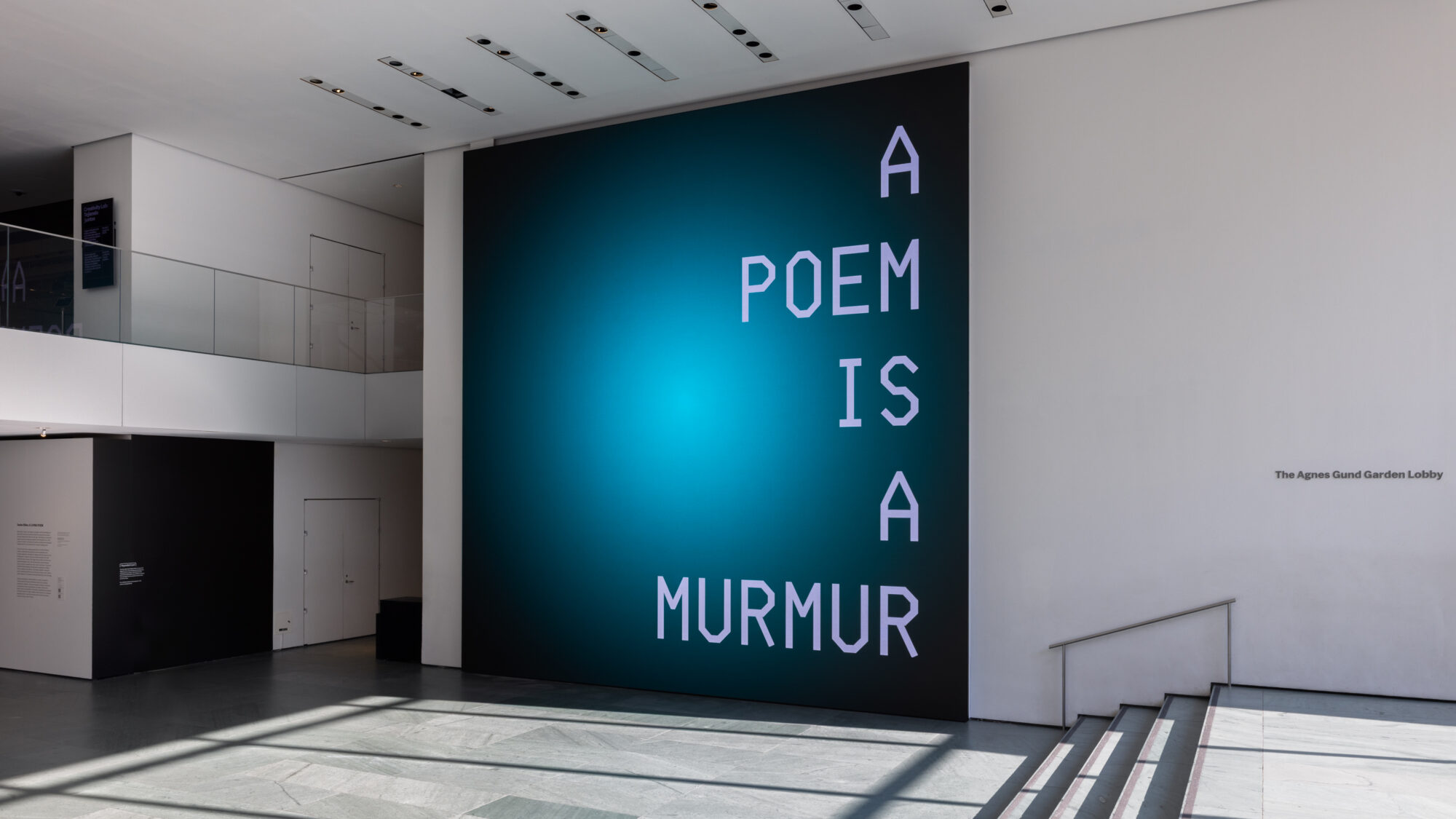

The art world acts as if it can opt out of all this, clinging to 20th-century notions of what culture is and how it circulates. When major institutions do engage with A.I., they tend to echo the technology’s promises of polish and ease, rather than probing its complications. A Living Poem by Sasha Stiles, a new commission for the lobby screen at the Museum of Modern Art, is the latest such example. By contrast, the most compelling work with digital technology that I saw in September is concerned with structure rather than surface. It’s personal, performance-driven, and grounded in DIY approaches.

Porpentine and Friends through Oct. 5

haul gallery | 24 15th Street, #207, Brooklyn

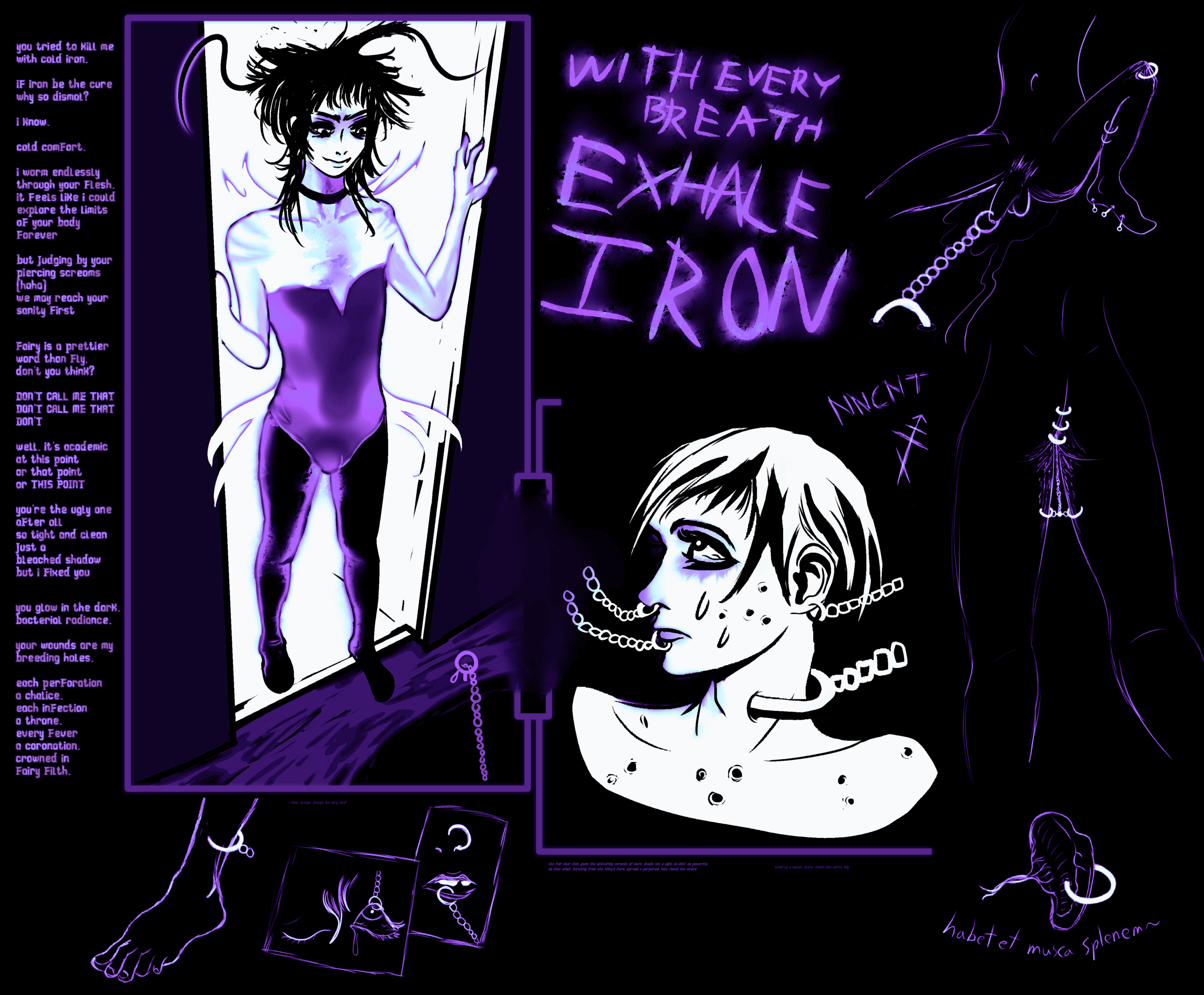

Porpentine is an artist, novelist, and game designer who makes work for, with, and about an online community of friends, fans, and “no world dreamers,” as they call their audience. They’re best known in the art world for their interactive fiction and other resource-light computer games: In the 2017 Whitney Biennial, Porpentine’s works (presented under the longer screen-name Porpentine Charity Heartscape) were exhibited in a kind of “net café,” where visitors were asked to sit at terminals and respond to text prompts as their play experiences were projected onto the walls. At haul gallery, a weekends-only space tucked away in a Gowanus warehouse, “Xrafstar World” gathers poster-prints of drawings that depict characters from their stories and games. Each of Porpentine’s compositions was made with a different digital brush—a game designer’s approach to art, a process with a built-in constraint. In Xrafmark Eruption (Cancer Rising), 2025, the effect is smudgy and warm, like finger-painting through glass. The figure is a superhero (or villain), half-human, half-fly, shown against an abstract ground—the same figure again, in negative, enlarged. The brush used in Cold Iron Fairy, 2023, is clean and blunt, like a marker, and most of it is black. The fairy hovers in a doorway, framed by computer-display text and graffiti, as though menacing a mortal creature with promises of pleasure. Pierced and shackled, the hapless subject’s irons are adornments and assaults.

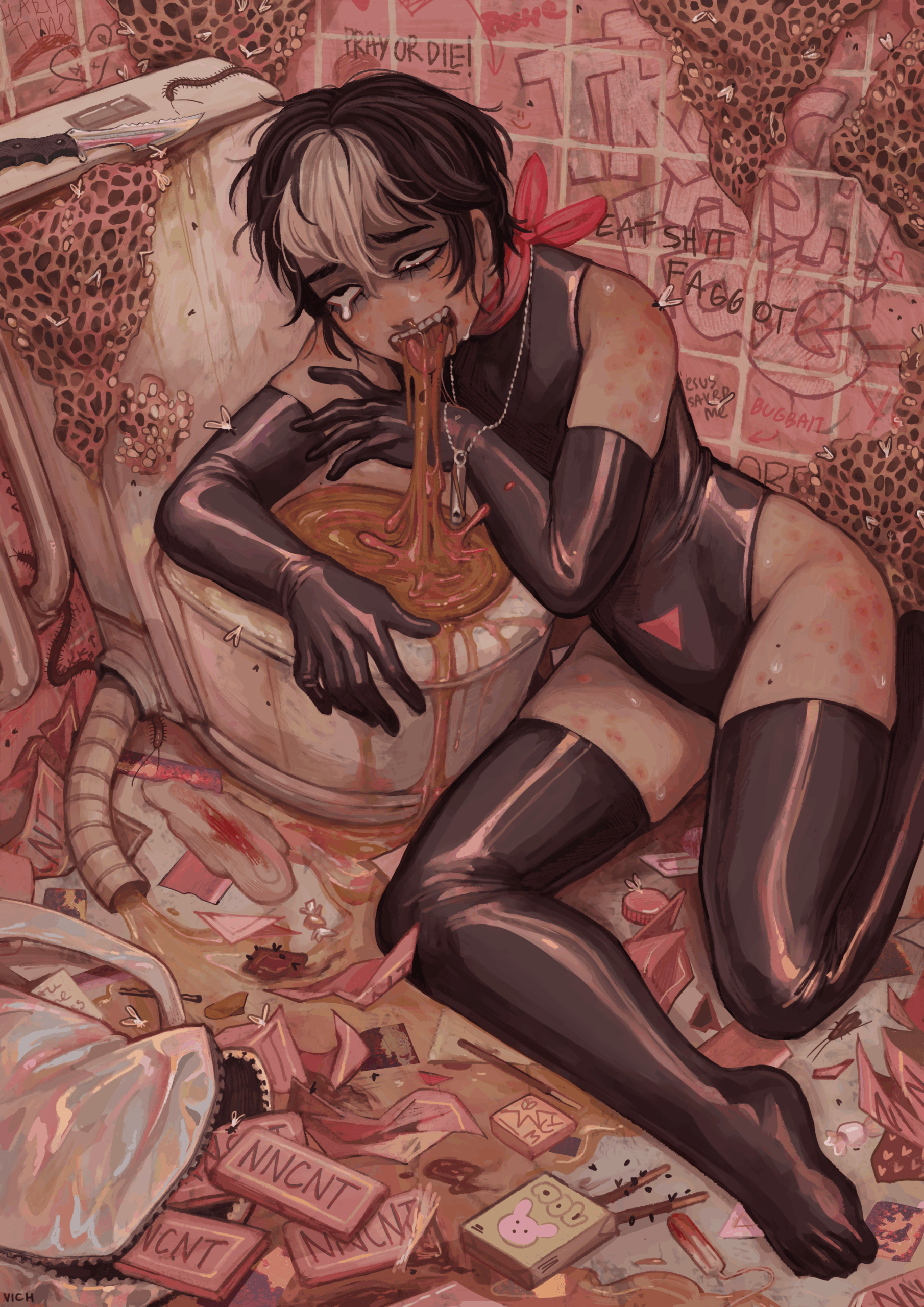

In a time when “trans ideology” (read: trans existence) is maligned as a terrorist plague, Porpentine embraces the classically dehumanizing category vermin for their “collection of androgynous bug boys.” (Xrafstar is a Zoroastrian term for repulsive animals.) This is not a sunny, sanitized reclamation. There’s desperation here, a depressed and lustful undercurrent. Some of the works on view—fan art made by others—reflect the conventions of digital illustration more than Porpentine’s own drawings do, but these images also wallow imaginatively in mixtures of gross emotions. Cancer Puke Cathedral, 2024, by Vich, shows a manga-styled kid vomiting into a toilet, swarmed by worms and flies. Their sick face is contorted in the cross-eyed ecstasy of ahegao. The art of “Xrafstar World”—offline objects that represent the characters and narratives of virtual spaces—trades in the codes of an in-group. Its casual, unpolished, but powerful, installation style reflects shared values and fears. And the work is priced in a way to sustain the circle—the big posters are $50, mid-sized ones $20.

Mindy Seu

A Sexual History of the Internet, 2025

Published by the Dark Forest Collective

While Porpentine operates at the scale of online subculture, artist and author Mindy Seu takes a top-down view of platforms and timelines in her book A Sexual History of the Internet, published in September. It’s a chic, 704-page, leather-bound volume that compiles artworks, scholarly citations, interviews, and other materials from networks of sex workers and activists. Last month at Pioneer Works I attended one of Seu’s readings, where she presented the book as a series of Instagram stories that we in the audience watched in sync. It was a performance conceived of as group screentime, a shared experience of something usually experienced in isolation. With the lights out, our faces were glued to our glowing phones as Seu wove through the seats with her mic.

Starting with the insight that “the iPhone is a sex toy,” a device that connects people with their desires, she noted that “cyberfeminism injected the cold, sterile, militaristic Internet with the slimy viscera of the body.” Platforms corral the slime so they can dose it on their own terms. And while the iPhone is a sex toy, it must stay dry. Seu’s performance transformed atomized experiences into a single shared one, mapping in-person togetherness onto online fragmentation—though the effect is far from utopian. The writing is inflected by Meta’s “community guidelines”—words like porn and pussy are spelled “p*rn” and “p*ssy,” mirroring how users skirt filters. Seu’s polished event achieved a certain kind of intimacy and a sense of collectivity; it also reminded us of how mediated and compromised connections facilitated by social media always are.

“to ignite our skin” through Dec. 22

SculpureCenter | 44-19 Purves Street, Queens

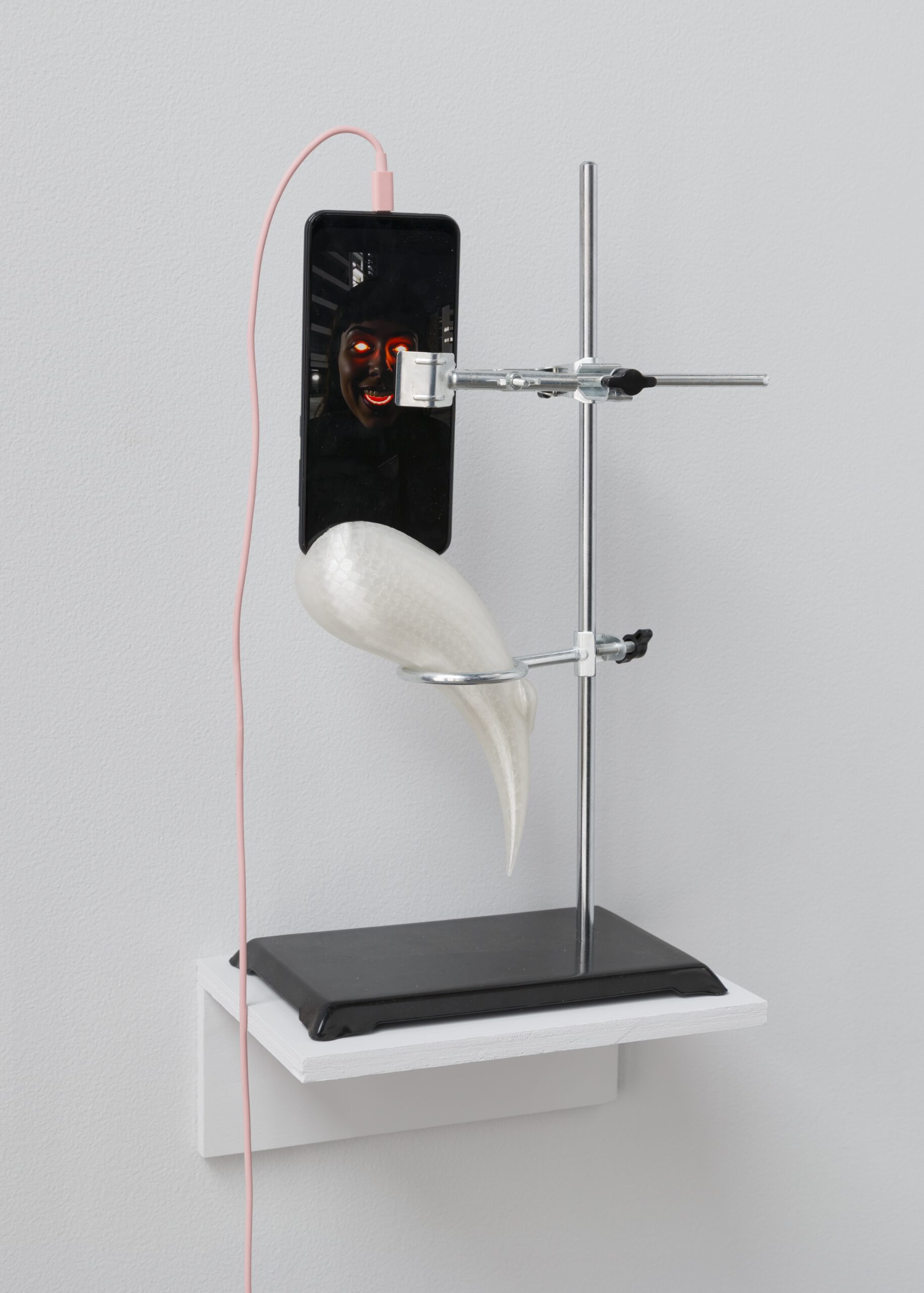

In a discussion of generative A.I.’s impact on sex work, Seu’s A Sexual History of the Internet mentions a project by Sarah Friend, who trained an A.I. model on images of herself and sold collectors the opportunity to prompt it. Prompt Baby, 2025, a series of works based on these exchanges, appears at SculptureCenter in “to ignite the skin,” a group exhibition about the body shedding and renewing itself. It’s a sensuous and solemn show, where soft, bruised textiles are offset with metal braces and armatures—abject matter disciplined by hard frames. Friend’s work is displayed on several iPhones as screen recordings that alternate collectors’ prompts with the images they yielded. (“A photo of Sarah Friend full length nude, body covered in tattoos of various hyperlane tokens… A photo of Sarah Friend with her body turned into a collection of 0s and 1s…”) The matte, pastel-toned phone cases and cords have the protective and rubbery look of medical equipment, their flexibility and palette drawing attention to them as prosthetic veins and nerves, extending bodily sensitivities and tastes. Translucent 3D-printed claws clutch the devices to hold them in place.

Friend’s work is tucked away in a small side gallery, presumably to protect viewers from the cartoon nudity in its “photos.” But the spatial isolation also makes curatorial sense because her approach to the body differs sharply from the familiar tropes of post-minimalist sculpture deployed in the rest of the show. The body here does not molt in pain and exposure. It sloughs off a digital layer that renews itself endlessly, a skin that protects even as it exposes.

Last month, Friend presented Artist’s Model, a performance-lecture expanding on the project, in an off-site program accompanying “to ignite the skin” at Onassis ONX. In it, she embodied her own A.I. model, speaking in a tone that was pliant and servile. She acknowledged A.I.’s role as an assistant while imagining it as a subject demanding consent. This conceit was sharpened through interactive segments, where she asked the audience questions and chose which chapter to present to us next after tallying the responses. Like Seu, Friend implicated us through our phones, making the collective tangible by way of individual devices. Yet here I felt more discomfort: We were invited to steer her performance, and in doing so, we pressed our preferences onto a figure who appeared both compliant and agentic. By interweaving the dynamics of consent into generative A.I. and live performance, Friend emphasized the unsettling aspects of both.

This tension is characteristic of Friend’s work. Her NFT collections—released on an anything-goes online art market without galleries to broker contact between artists and their patrons—often include coded conditions that make collectors active participants in the work. For example, her Lifeforms, 2021, demand care; they “die” (disappear from a crypto wallet) if they aren’t transferred to someone else within 90 days. Similarly, the interactive format of Artist’s Model illuminates the social dimensions of Prompt Baby. It folds attention back onto Friend’s personhood, while dramatizing how entangled that self is with the technologies that absorb, organize, and negotiate interpersonal connection.

Sasha Stiles through Spring 2026

Museum of Modern Art | 11 West 53rd Street

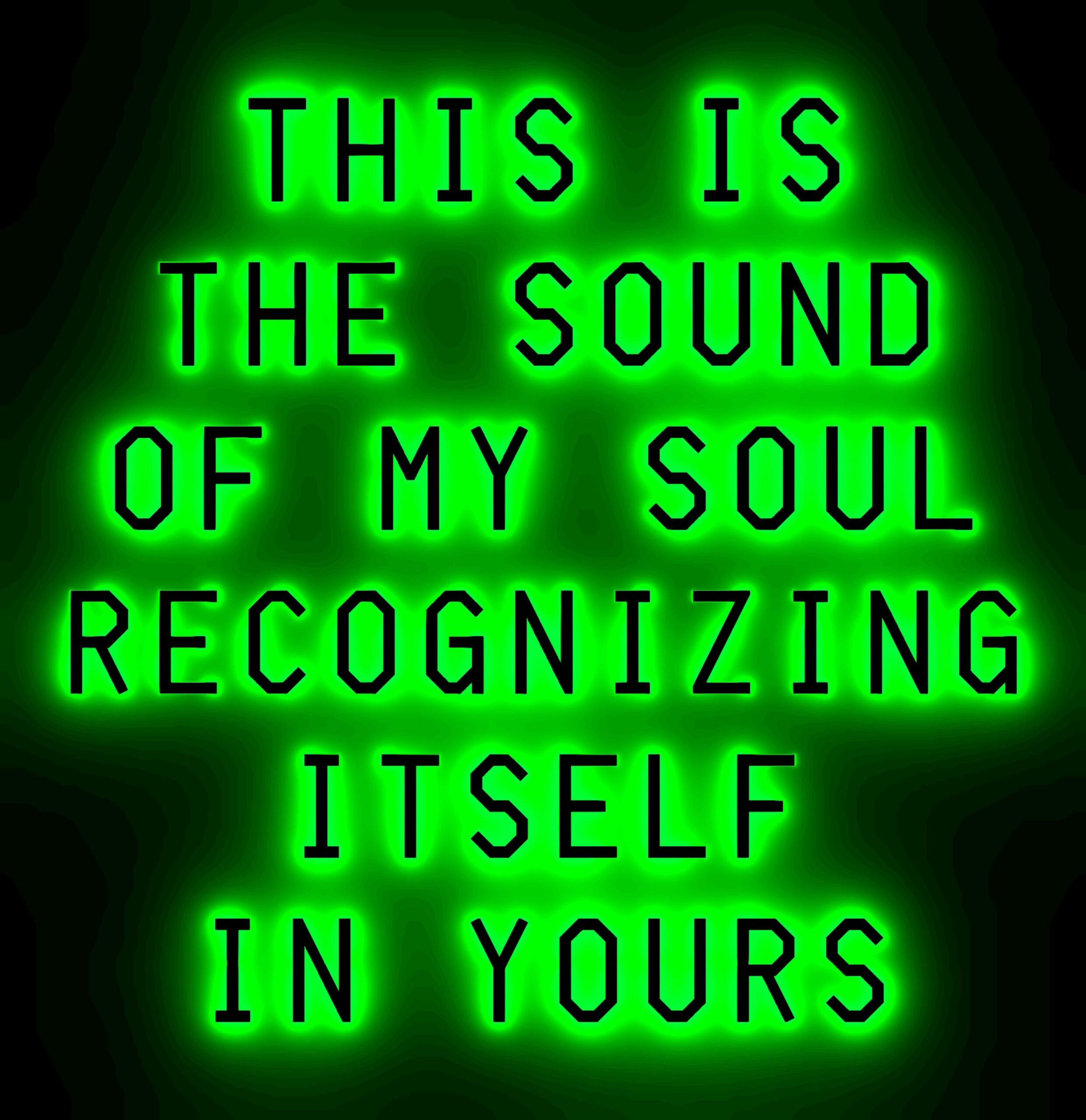

I suspect that most art audiences don’t encounter work that foregrounds the social and ethical complexities of A.I. the way Friend’s does. Sasha Stiles’s A Living Poem, created for MoMA’s lobby screen, gestures toward similar concerns but favors atmosphere over entanglement. Glowing in pinks and greens against a black field, the piece’s aesthetic recalls the look of early computer terminals, but it uses the layering effects of contemporary imaging software—a nostalgic anachronism. A Living Poem builds on the work the artist did to create her 2022 poetry collection Technelegy, for which some poems were composed with an eponymous customized A.I. model. But the best pieces in that book—those in which speculative futures tumble forth in kaleidoscopic cascades—were the ones written entirely by Stiles herself.

Each hour-long iteration of A Living Poem collages text fragments generated in real time and assigned visual identities from a predetermined set. This is not a poetry of lines and stanzas—it’s text-as-image, language arranged to be looked at. Arguably, this suits the project for museum presentation, as many viewers will have been primed for it by the work of artists like Jenny Holzer or Barbara Kruger. But Holzer and Kruger manipulate and mock the language of power. Stiles and Technelegy’s output lacks that ironic, ideological bite. Instead, they offer gee-whiz musings about creativity and its automation. “This poem is the gravity between souls,” “This poem is stardust arranging itself into meaning,” “This poem belongs to everyone and no one.” The A.I. model gazes at its non-existent navel.

A Living Poem is the fourth work to appear on MoMA’s lobby screen since it was inaugurated in 2022 with Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised. A wall text states that A Living Poem is written “in dialogue” with works by Holzer, Kruger, Lawrence Weiner, and others from MoMA’s collection, which is to say that, like Unsupervised, the work translates the museum’s collection into latent space, reducing it to nubby representations from which it can grow new forms. The precedents are no longer recognizable. Fifteen years ago, museums were busy digitizing their holdings so they could be accessible online. Now, MoMA is opening its data up for use as raw material, not to index artworks, so that audiences can see how they’re unique, but to render them as training sets, ready for endless reorganization.

Works like A Living Poem and Unsupervised make a certain sense as lobby art—glowing selfie backdrops that double as ambient introductions to the collection. I don’t expect an institution like MoMA to stage the kind of visceral, intimate confrontations between bodies and technologies that can be found in performances or small Brooklyn galleries. But museums can choose not to become data centers that grind their collections into digital slurry. MoMA has opted in so hard to A.I. that it’s another way of opting out—gliding over what’s happening now on the smooth, opaque surface of the tech demo.

in your life?

in your life?